Sometimes I am asked if I think there is hope for Haiti. I have heard this question more and more as we approach the end of 2016, a year that has not been kind to Haiti.

I always say first that four reporting assignments do not make me an expert on Haiti. I can only relate what I have seen and experienced. With that caveat, I do say this: On day one of my most recent assignment for Global Sisters Report, I felt hopeful. There was energy in the air.

But by day three, I felt frustrated. True, the capital of Port-au-Prince looked better than when I last saw it in the year after the devastating 2010 earthquake. But digging deeper, I discovered that a lot had not changed.

That leads to the inevitable questions: why the endless grind of poverty, hunger and injustice never seems to end, why so many roads still aren't paved, and why traffic seems to get worse and worse every year — why the same problems and dynamics, like corruption, never seem to get solved.

But by day seven, a week into the assignment, I felt hopeful again. And that is because Haitians are resilient. They improvise and adapt like no one else and are as tough as can be. They are also, as nearly every Catholic sister I met on assignment observed, a faith-filled people whose love of God is probably unmatched.

"You see the hope against hope, the faith, the determination, the perseverance, the hard work, the endurance of people," said Sr. Annamma Augustine, an Indian Missionary Sister of the Immaculate Heart, whose congregation is known as ICM Sisters.

"From where they get that strength, I don't know," said Augustine, who has lived and worked in Haiti for 32 years. "Life continues to be hard for the people. They move on with courage. God gives them hope and life in spite of everything."

Augustine's praise should not be mistaken for romanticizing Haiti or Haitians. She acknowledges being as frustrated as anyone about the particular dynamics Haiti faces.

"When the basic needs are not being met, the trees cannot grow," Augustine said, using a metaphor about trees growing in barren soil.

Augustine sees political leadership as a key to Haiti's future. And it's a tough balance, she said, between respect for democratic institutions and populist strivings and the need for strong, innovative leadership.

Many older Haitians, she said, see a country with no clear direction and sometimes will express nostalgia for the era of the Duvalier family. (François "Papa Doc" Duvalier ran the country with an iron fist from 1957 to 1971 and was succeeded by his son, Jean-Claude, who was driven out of office in 1986 by protests following years of human rights abuses.)

My guess is that most of the country would not want a return to that era. For one thing, an increasingly younger country has no memory of the Duvaliers. But bolder, more creative and attentive leadership would be welcome, Augustine and other sisters told me.

"What would be best is political stability, a good leader and more investment in the country," Augustine said.

Haitians I met agreed and added that what is needed most in Haiti is tempering a way-too-engrained sense of individualism and coming together in a more cooperative way to heal years of political divisions.

"It is true, the society is divided and is not working together," said Corrielan Thérése Moléron, a member of Source of Life, a women's self-help group in Port-au-Prince that is organized by the ICM Sisters.

Moléron and others said they don't trust politicians, and they are proud that their quiet, "below-the-radar" grass-roots efforts serve as an alternative model for society.

After the 2010 earthquake, Augustine's congregation recruited Moléron and other women to distribute food to those who needed it. After that, the sisters gave the women start-up loans so they could develop small-scale, income-generating projects to provide income for themselves and boost the economies of their neighborhoods. A number chose cooking projects, providing inexpensive meals for those who needed them.

"It's mutual support for a better life," said fellow self-help group member Rosemène Joanis. "It's been a success. We weren't doing anything before. It helps us, and it helps our families."

The group has expanded to more than four dozen women.

"It's beautiful. We come together. We support each other. We have confidence in one another," Joanis said.

It is also a place, said group member Perpetue Maurice, where women, who are so often burdened by family responsibilities and a legacy of male domination in Haitian society, can "express ourselves."

Of course, such groups have their own set of challenges and cannot meet all of the demands of a country facing so many problems. Providing meals on street corners won't solve the larger challenge of hunger in Haiti, which is substantial. Malnourishment is a condition known to at least half of Haitians, according to the World Food Program and other U.N. agencies.

A fresh round of hope and skepticism

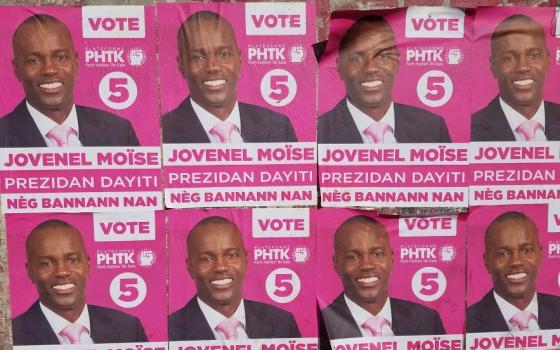

The issue of food and hunger is being championed by Jovenel Moïse, who won the November 20 Haitian presidential election with more than 50 percent of the vote: an unexpected development, considering Moïse, a plantation owner who embraced the nickname "Banana Man" during the campaign, was one of 27 candidates in the race.

In a post-election interview with Reuters, Moïse, a protégé of former President Michel Martelly, said agriculture and food security — defined by the U.N. as the condition in which people "have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet dietary needs for a productive and healthy life" — would be priorities in his administration.

"I can't say in five years I will make Haiti 100 percent self-sufficient" in food, Moïse told Reuters. But, he added, "I think that if Haiti is not self-sufficient in food, it is because we have stopped working."

So far, Moïse has gotten mixed reviews, to say the least. Political protests on the streets by Moïse's opponents marked the announcement of his election win, though that is common following Haitian national elections. (The election results will be officially verified December 29.)

As for Martelly, who left office in February and was succeeded by an interim leader, I heard some Haitians criticize him and his family for corruption and financial gains made while he was president. At the same time, a number of people, including sisters, praised the former president for some improvements in infrastructure and for being visible to people during natural disasters. A number of other Haitian leaders were perceived as going AWOL during the 2010 earthquake.

There were other welcome changes under Martelly's leadership, some sisters said.

"President Martelly made some important inroads in our area with his education program, which unfortunately came to a halt when he left office," said Sr. Fidelis Rubbo, who lived and worked in Haiti from 2001 to 2014 and traveled recently to southern Haiti as part of an emergency response team that worked in areas badly affected by Hurricane Matthew. "Children and schools are back to where they were before [he became president in 2011], it seems."

It will be worth following to see if Moïse picks up where Martelly left off in this area. But on the critical issue of hunger, the sisters I spoke to recently said Moïse's embrace of the issue is most welcome, as it is an issue that engages them all of the time.

"If [Moïse's] election stands, I can only pray that he will follow through with this as a top priority," said Sr. Janet Lehmann, the director of the nursing program of the University of Notre Dame Haiti's Jacmel campus. She noted in an earlier interview with GSR that the "lack of food and malnutrition affect health" of Haitians in all sorts of ways.

Other sisters in Jacmel — which was badly hit, though not crippled, by the hurricane — said the issue of hunger remains worrying.

"It seems as though there is more hunger everywhere and, of course, no money," said Felician Sr. Marilyn Marie Minter, who has worked in Haiti in full-time mission work since 2012. "It seems more difficult. Seems to us people's attitude is, 'I don't care because the leaders in the past have not helped us, and it will be the same old thing.'"

Based on Rubbo's work in the Grande Anse area, "where Hurricane Matthew devastated almost all of the people's means to obtain food," Rubbo said she hopes Moïse follows through on his commitment.

But needs still remain great in hurricane-affected areas, she said.

"What has discouraged me since Matthew is that despite all our efforts these last two months, no large-scale efforts to distribute food have reached back into the off-road areas of the mountains in the Pestel commune and in at least half of the villages along the main road," Rubbo said.

"What gives me hope are the small NGOs who continue to tough it out trying to serve the most needy," she said. "And even more is the generosity and courage of Haitians who are selflessly assisting them in reaching the most destitute."

Political leaders in Haiti are like politicians elsewhere: They say things in campaigns then ignore them once they take office. But Haitians seem particularly cynical about their leaders. Much of that has to do with a legacy of corruption and self-enrichment that may be too strong and too deeply embedded in the political fabric to resist.

"We have no hope for politicians," Moléron said. "They get into power and then get worse."

Joanis was equally skeptical. "I will wait and see what happens, but there's not much hope with politicians."

I hope President-elect Moïse takes that criticism to heart and listens to women like Moléron and Joanis, who believe in naming a problem, working on it and tackling it cooperatively — all with integrity. By doing that, they are offering much-needed hope for Haiti.

In Jacmel, Minter sees similar dynamics.

"There is always hope for Haiti because where there is life, there is hope," she said. "Life needs to be embraced every day, one relationship at a time."

[Chris Herlinger is GSR international correspondent. His email address is cherlinger@ncronline.org.]