What good does the United Nations do?

The often-asked question about the world body always comes up during major events and meetings, like the just-concluded 61st annual session of Commission on the Status of Women, or, in U.N. shorthand, CSW 61.

Even those who admire the U.N. and advocate for its work — like the many Catholic sisters at the U.N. — ask the question.

The Commission on the Status of Women is a U.N.-based intergovernmental body "exclusively dedicated to the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of women" and makes recommendations to the U.N.'s Economic and Social Council. Representatives of 45 U.N. member states meet annually for two weeks in the spring for numerous meetings and conferences at U.N. headquarters in New York, with U.N. organizations and civil-society and nongovernmental groups like Catholic sisters also participating.

As the March 13-24 meetings winded down, I heard Sr. Winifred Doherty, the U.N. representative of the Congregation of Our Lady of Charity of the Good Shepherd, speak publicly, and quite passionately, about the U.N.'s penchant for words and declarations. She sounded frustrated, even declaring at one point, "What are we doing here for two weeks?"

"We don't need any more words," she said at a March 22 event sponsored by the Sisters of Mercy/Mercy International Association, talking specifically about the theme of this year's meetings: women and the changing world of work.

"All of our [women's] 'services' are outside the political," she said, adding that U.N. member states still do not do enough to enact the laws within their countries to make a real difference to women.

"We need policies, laws, we need investment, we need partnerships, we need women's collective voices," she said. "From the moment of birth, women and girls are robbed of their dignity."

No one is more dedicated to the work of the U.N. than Doherty and her Catholic sister colleagues. But the sisters recognize that while the U.N. is useful for highlighting issues and pushing nations in a certain direction — no small matter — the bulk of social change has to be done within countries and locally.

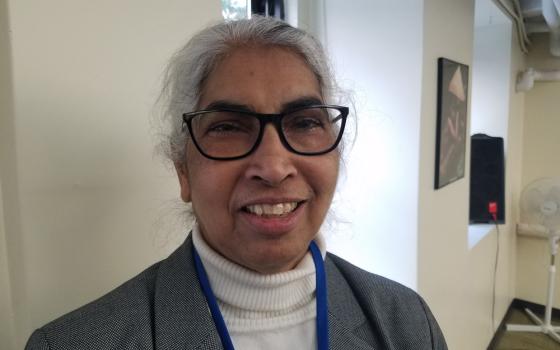

"We can talk about gender equality and women's empowerment at the U.N., but the narrative has to change at the grassroots," Sr. Teresa Kotturan, the representative at the United Nations for the Sisters of Charity Federation, told me earlier this week.

In a separate interview, Sr. Margaret Mayce, who represents the Dominican Leadership Conference at the U.N., sounded a similar note of humility about the world body.

"It's not a question of, 'Let's give the poor women power,' " she said. "We have to remove the obstacles that impede women's capacity to exercise the power that is already theirs."

At a March 17 presentation hosted by The Temple of Understanding, an interfaith organization, Sr. Celine Paramunda, the Medical Mission Sisters' representative at the U.N., repeated the theme of women's power to effect change and the need to remove impediments that make that difficult, such as gender discrimination and poverty.

But she did so in the context of the need for grassroots movements to push national and international bodies on issues such as mining and extraction and "land grabs" that have a direct bearing on the health of the environment. The women who are already dealing with these issues directly are "becoming the agents of change," Paramunda said.

The "outcome document" of the two-week conference amounted to a pledge, though not a legally binding one, for change by U.N. members.

The commission is made up of 45 member states that rotate every four years. The United States is not currently a commission member. Resolutions from the commission have at least two stages of approval ahead of them: the United Nations' Economic and Social Council and, eventually, the U.N. General Assembly.

Most U.N. resolutions, like the ones coming out of the Commission on the Status of Women, are not binding.

"The idea, of course, is that all U.N. member states will make an effort to follow through on the recommendations in the document," Mayce told me. The only resolutions states are obliged to follow are treaties or those coming out of the U.N. Security Council.

The commission committed to the goal of women's equality in the workplace and to close a wage gap between men and women.

"Despite the long-standing existence of international labour standards on equal pay, the gender pay gap, which currently stands at 23 per cent globally, persists in all countries," UN Women, the United Nations' women's arm, said in a statement. U.N. member states participating in the conference, the statement went on to say, committed to "equal pay policies through social dialogue, collective bargaining, job evaluations and gender pay audits, among other measures."

The outcome document also acknowledges a number of issues and trends becoming global concerns. One is about the importance of "fully engaging men and boys as agents and beneficiaries of change for the achievement of gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls," as the document put it. I heard this theme a number of times at the conference, and it will be interesting to see if this push has any effect. (Are my fellow men willing to step up and acknowledge this?)

Another major concern noted in the outcome document is the issue of unpaid work, in particular that "women's contribution to the home, including unpaid care and domestic work, which is still not adequately recognized, generates human and social capital essential for social and economic development."

Elsewhere, the commission said it recognized that "women and girls undertake a disproportionate share of unpaid care and domestic work, including caring for children, older persons, persons with disabilities, persons living with HIV and AIDS and that such uneven distribution of responsibilities is a significant constraint on women's and girl's completion or progress in education, on women's entry and re-entry and advancement in the paid labour market and on their economic opportunities and entrepreneurial activities, and can result in gaps in both social protection and pension."

The commission said it sees the need "to recognize, reduce and redistribute the disproportionate share of unpaid care and domestic work by promoting the equal sharing of responsibilities between women and men and by prioritizing ... social protection policies and infrastructure development."

The issue of unpaid work was a repeated concern I heard from Catholic sisters and others.

"Reports show that women do at least twice as much unpaid work as men. In parts of the world, the gap is wider," said Sr. Margaret O'Dwyer of the Company of the Daughters of Charity. "Unpaid work includes activities such as child care, collecting firewood, finding water, caring for the sick or elderly, tending to vegetables in the family garden, domestic work, and the like."

"I think people get that everyone needs to contribute to their household," she said. "But for many women and girls, particularly those living in poverty, unpaid work demands mean they can't complete an education, acquire a paid job or career, or earn a pension. Some work is so hard they never have free time."

In addition, O'Dwyer said, unpaid work is typically not included in calculating a country's gross domestic product.

"If the dignity of women and girls is to be respected, if they are to be empowered, this has to change," O'Dwyer said.

She said the commission did well by expressing "concern about gender stereotypes and negative social norms, which serve as structural barriers to women's economic empowerment." She also praised the commission's attention to the needs of women with disabilities and of migrant women and was happy that the commission took up the issue of unpaid care work.

In the end, O'Dwyer said the commission's final document is an appeal to "governments and regional organizations to take steps to address root causes of gender inequality, gender stereotypes and unequal power relationships."

"That task will not be easy, as it requires overcoming social norms, traditions and stereotypes. If we truly believe each person should have the opportunity to reach their full potential, it needs to happen."

Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, executive director of UN Women, made a similar point as the commission ended its two weeks of meetings.

"There has never been any excuse for the inequality that exists," she said in a statement. "Now we are seeing a healthy intolerance for inequality grow into firm and positive change."

As the commission weighs possibly taking up the challenges indigenous women face at next year's meetings, the focus now turns to see if laws are enacted and enforced within nations and local communities to ease the burdens on all women.

"Now, we shall see if political will at all levels is strong enough to make it happen," O'Dwyer said.

[Chris Herlinger is GSR international correspondent. His email address is cherlinger@ncronline.org. Ursuline Sr. Michele Morek, GSR's sister liaison, contributed to this report.]