Notes from the Field includes reports from young people volunteering in ministries of Catholic sisters. A partnership with Catholic Volunteer Network, the project began in the summer of 2015. This is our ninth round of bloggers: Samantha Wirth is the public policy fellow for Good Shepherd Services in New York City and Adele McKiernan is a Loretto Volunteer at Missouri Health Care for All in St. Louis.

___

Author's note: This piece refers to whiteness. While its definition has shifted over time, I am using one from this article, which applies well to the way I am using the word in this piece: "Distinct from being white, whiteness refers to an unmarked and unnamed place of advantage, privilege or domination; a lens through which white people tend to see themselves and others; an organizing principle that shapes institutions, policies, and social relations."

In a society built on white supremacy, we must be willing and able to look both inside ourselves and at the policies in place that make up the rules and culture that guide our lives in order for change to be meaningful. I believe intentional communities focused on social justice have the capacity to bridge and merge personal and political forces by engaging us in critical thinking and fostering an environment where systems of oppression are talked about openly.

Sadly, this has mostly not been the case in the St. Louis Loretto house.

I quickly realized at the start of my volunteer year that I had a lot of room for growth in my understanding of privilege and racism. But without the foundational trust necessary for our community to broach these topics organically or a formal framework for them built into the program, I began to unpack my whiteness and its implications independently.

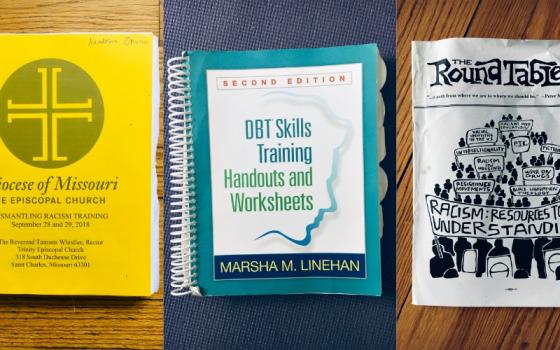

I did so by turning to a familiar psychological framework called dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT). I was originally introduced to this to manage specific mental health symptoms but have found it to be helpful in many areas of my life. It has been especially helpful for addressing symptoms of depression and enhancing self-worth.

But as I read and thought more about the insidious structures that still underpinned my newfound self-concept, intentionally not asking me to think too much about my privilege, familiar feelings returned. This time, existential dread, anxiety and self-doubt were mostly focused on my culpability in systems of political oppression, violence and power. Though they were enhanced by my propensity for intense emotion, these felt distinct from symptoms and were harder to process in therapy.

Without space built into the Loretto Volunteer Program to process my experiences communally, I began to use DBT skills to move through the emotional stages of reckoning with whiteness. Along with books, articles, poetry and social media resources, I used mindfulness skills to intentionally break down implicit biases; self-soothing skills to help me move past white guilt without asking for unnecessary reassurance from others; and what are called behavior chains to analyze and learn from interpersonal interactions centered on race.

For me, reckoning with my mental illness and reckoning with whiteness both became existential experiences requiring vulnerability, introspection and mindfulness. Yet while similar skills are relevant to both, this framework is mostly theoretical and hyperspecific.

Introspection without structural support forces us to process on a personal level, while whiteness is systemic and shared. It forces us to use skills we already have, ultimately limiting growth and reinforcing distance. While communal processing can be difficult, it builds accountability and pushes back on white constructs of individualism, objectivity and fear of conflict.

This is where I see the opportunity for growth in the Loretto Volunteer Program: forging explicit pathways for volunteers to have crucial discussions about racial identity in houses and at retreats in ways that honor skill- and knowledge-sharing among volunteers, while ensuring people of color aren't tokenized and asked to do additional emotional labor.

As I've talked with current and past volunteers in Loretto, it has become clear that whiteness is preventing the program from being thoroughly inclusive of people of color. It's generally agreed upon by this year's cohort of Loretto volunteers that there is not yet a program infrastructure and culture that adequately acknowledges racial power imbalances within volunteer houses, between volunteers and placement staff, and within the community as a whole.

As a result, there have not been consistent or timely responses to volunteer curiosity and concern about power and privilege within Loretto or enough attention dedicated to racial tension, bias and microaggressions in houses or the workplace.

This is not unique to Loretto (or volunteer corps). One of my fellow volunteers, Isabel Ngo, who is placed in El Paso, Texas, wrote a recent article for The Los Angeles Loyolan called "A lack of support for volunteers of color in post grad-service programs," in which she interviews volunteers and staff in multiple service organizations about the ways in which race shows up in their programs. Reading Isabel's account of how volunteer corps can and do advance justice — such as issuing an equity newsletter, incorporating affinity groups, and building in "channels of feedback" for volunteers of color — serves as a reminder that these can be done in Loretto, too.

I have seen positive developments over the past month that show Loretto responding to this need for change. My house has just started a series of facilitated racial justice conversations intended to work through the ways race has shown up in our community. Our program coordinator will also be consulting with the facilitators to improve Loretto's program policies to make them more equitable and inclusive.

We are thinking more critically about the location of our house (in a mostly white suburb in a deeply segregated city) and what that means for volunteers who are not white. We also had a few co-members over to our house and had a productive conversation around barriers of access to the Loretto community.

I make no claim to solutions and have an infinite amount of personal work still to do. Yet I have seen growth in myself and see our capacity for collective and institutional growth. As part of the youngest generation of Loretto and a returning volunteer, I hope we will examine our history, culture and policies so we can situate ourselves to be able to work for justice and act for peace from the inside out and welcome more people to this pursuit.

Thank you to Loretto Volunteers Brianna Neilson and Isabel Ngo for edits to earlier drafts of this piece.

[Adele McKiernan is a Loretto Volunteer in St. Louis working at Missouri Health Care for All as an organizing fellow.]