This time of year is filled with national and family rituals ushering in the New Year filled with hopes. We all hope for a second chance to accomplish what has eluded us in the past. We all hope for the darkness of the previous year to be gone and the light of the New Year to bring us unfulfilled dreams and goals. Winter Solstice celebrations start December 21 where fires keep burning throughout the night; vigorous singing and dancing deny that darkness will triumph and that hope of new light will come.

December 31 is the contemporary celebration of hope, also a time of singing and dancing away the past year and welcoming the new. Christians are reminded in Wisdom 18:14 of hope that God will be faithful: “When peaceful silence lay over all, and the night had run its course, down from the heavens, from the royal throne leapt your all-powerful word; into the heart of a doomed land. . . .”

In many parts of our world people do indeed feel doomed and hopeless about their children’s futures. Some are prisoners in their own homes as war is waged around them with no place to go if they leave. Some are imprisoned in refugee camps for life. Sisters worldwide are often bearers of hope for people suffering these circumstances.

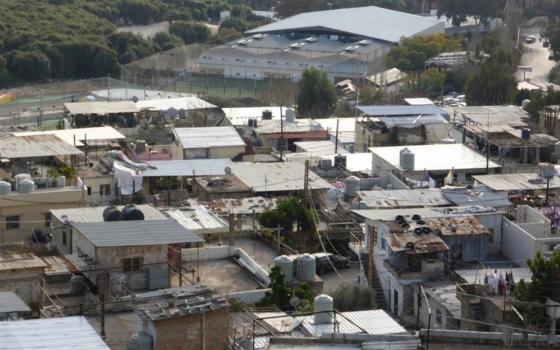

Sr. Johanna Gyhoot, a Little Sister of Nazareth, from Belgium is one of these. She ministers to 5,000 families in a refugee camp in Beirut, Lebanon. Two hundred of them arrived from Syria two years ago. The camp is the only Christian Palestinian one in the country, and being a Christian in a Muslim nation is a great disadvantage. Discrimination keeps Palestinian families from obtaining legal status no matter how long they are in Lebanon. Without documentation finding jobs to support their children is next to impossible. Insecurity is kept at bay for a few who find day work as drivers, fishermen or construction workers. But future insecurity is almost a given for their children as there are no schools in the camp. Fees for tuition, uniforms and transportation to attend schools outside the camp are beyond most families’ capability.

Youth seek any job offered to get out of Lebanon, but those without connections are left behind. The camp is filled with the poor, particularly women with children left to fend for themselves. Male family members who find jobs abroad may come back to visit once or twice a year, but some just give up reuniting with their families. Others are soldiers who may or may not return.

Sr. Johanna, a trained nurse, begins her ministry visits to families at 6:30 each morning, using Arabic she learned in 2006 when she was assigned here. She identifies and attends to their health needs with the help of volunteer doctors and psychologists who come a few times each week. Financial aid for health care and food comes from private donors, foundations in Europe and the United States and St. Elizabeth University in Slovakia, the sponsor of Sr. Johanna.

Much of Sister’s time is spent listening to the pain mothers and children carry with them from Syria or elsewhere. She shared that her saddest experience at the camp was finding a Palestinian mother suffering from severe mental illness struggling to care for her three children. “They had so much against them to succeed.” The woman’s parents wanted to be rid of her, so married her off at an early age to a soldier. This man is gone for long periods of time, visiting occasionally, leaving behind a little money, but never enough to support the needs. With the help of donors Sr. Johanna enrolled the children in a boarding school in the city. Staying at home and coping with their mother’s erratic behavior and abuse proved too difficult while attending day school. At the school the children learned skills to care for and manage their mother’s illness. The oldest girl will soon graduate and take on the responsibility of the family bread winner. So although the mother will never get well, Sr. Johanna’s support and attention gives the family hope and capacity to manage.

Sr. Johanna fell in love with refugee work in Antwerpen, Belgium, in 2003 where she met a young pregnant woman and her four children escaped from Syria. She found them in a completely empty house. Mother and children had been on the run for three years, moving from place to place unable to pay the rent. Each move was made with smugglers whereby she and the children were hidden in a truck and the kids given medicine to keep them quiet at border stops.

Sr. Johanna was attracted to work with the poor growing up in a family where her parents engaged in the French Catholic Worker Movement. She joined the small community inspired by Charles de Foucauld. The current 40 sisters are missioned to the poor in Belgium, France, Spain, Venezuela, Colombia and Lebanon. She described the heart of their spirituality as a friendship that offers love and hope to those most rejected.

As she shared her story I was reminded of Karl Rahner’s description of hope in The Practice of Faith (p. 260): Hope is “courage to commit oneself in thought and deed to the incomprehensible and uncontrollable which permeates our existence, and, as the future to which it is open, sustains it . . . a courage [that] has the power to dare more than what can be arrived at merely by planning and calculations. . . .” This definitely describes life of hope often found in refugee camps around the world.

[Joyce Meyer, PBVM, is international liaison for Global Sisters Report.]