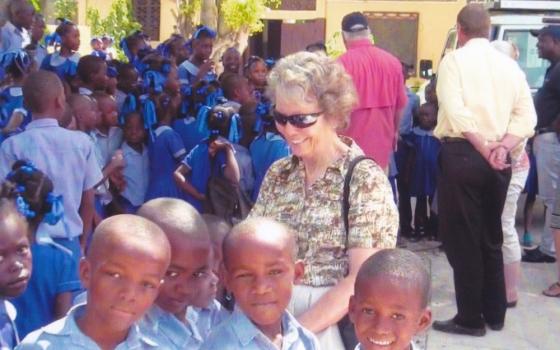

Haiti is not a usual tourist destination but since I was there in 2009 there have been many changes that make it more inviting. The airport is sparkling new, even though the lines are still long with missionaries from the U.S. evangelical churches. There are new hotels far from the wealthy area of the old city nestled among ancient, dilapidated shops making me wonder if they were built with the motto “Build it and they will come.” Perhaps new buildings will inspire other investors. Who knows! The main streets are better, but driving is still hectic and the road up the mountainside to the Little Sisters of St. Therese of the Child Jesus is still steep and rocky. My companions and I saw families sitting outside post-2010-earthquake temporary structures and washing clothes in the river down in the valley. Trucks frequently blocked our way selling water to the mountain dwellers.

Although there were times I felt dizzy looking over the edges of the unprotected cliff road, we were very excited to be visiting a new project of the Little Sisters of St. Therese of the Child Jesus, 11 other sisters’ congregations and Medicines for Humanity, an NGO from Boston. To have so many congregations participating in one project together is new one for Haiti. But, the sisters are convinced that to have the greatest impact and learning potential it is imperative to work together. It makes them more than ever agents of change.

And, needless to say, being agents of change is part of sisters’ call. They are driven to it, not so much by human motivation, but by the Gospel and the gifts of the Spirit. The Gospel is their lens of perception into need and ignites them to do something about it. Its energies change status quo into new vibrant and life giving realities. Sisters around the globe are constantly changing water into wine or multiplying loaves and fishes to feed the hungry and weary. Although the miracles may not be literal they are most certainly accomplished within the confines of scarcity.

This new collaboration among sisters in Haiti and Medicines for Humanity is another example. It is also a perfect match with Medicines for Humanity’s commitment to make sure that children under 5, and their mothers, thrive — a mission shared by all these sisters of Haiti. The Little Sisters alone manage 17 small clinics and three hospitals scattered throughout the country. They insist that their most imperative need at the moment is to become midwife trainers. Most women deliver their children at home, thus having well trained, skilled traditional midwives in remote mountain villages is essential for safe birthing and maternal care.

The Sisters, Medicines for Humanity, and the Haiti Ministry for Health designed the program together and invited other congregations to participate. Some of the sisters are missionaries from other countries including Nigeria and Tanzania. They work primarily in remote areas where there is little opportunity for such training. The second stage of the program will focus on skills development for managing public health outreach in those same regions of Haiti.

The midwife training program began in May in a sparkling new, two-story clinic of Riviere Froid, a section of Port-au-Prince, where the Little Sisters of St. Therese of the Holy Child Jesus are headquartered. It replaces the original dilapidated one where I could barely squeeze my way down its dark halls. The new place is like a dream come true. The only thing lacking is water. That has to be purchased from those delivery trucks traversing the mountainsides.

Sister Marta (Marie Jeanne Martha Pantal) is the director of this new program and in a recent interview she spoke passionately about her dreams for health care services in Haiti:

Sister Marta is one of the 200 Little Sisters of St. Therese of the Child Jesus who experience the Gospel’s power of change and of resilience every day of their lives. On January 12, 2010, they were hit hard by the earthquake that took sisters’ lives, five schools, eight convents, and 12 hospital buildings. Even their motherhouse was badly shaken, and sisters had to vacate it for fear that after-shocks would demolish the entire structure. They lived for several weeks in tents with their neighbors. Deaths of members and many students who were in the school that collapsed next door added to their fear and grief. I will never forget the pictures of those little bodies laid side by side on the ground as they were discovered in the debris, one by one.

My visit in June witnessed the resilience of the Little Sisters. Five and a half years later, there has been recovery, but they still have a long way to go. Rebuilding damaged structures in Port-au-Prince and outlying areas and renovating their motherhouse are all on hold until donors can be found. Finding people to contribute to these efforts is a challenging feat in Haiti. Island isolation from the interest of the rest of the world and the difficulties of national infrastructure, politics and costs make development slow going and mostly stagnant. Grants from outside agencies helped rebuild the school and a small house nearby, but the sisters’ loss of many of their ministries also meant loss of income potential. Financial reserves were quickly eaten up.

The sisters’ greatest resource is its members. They have been fortunate to have a steady flow of new entrants over the years. Missionary congregations from France and Canada were part of early development of Haiti, but the Little Sisters of St. Therese of the Child Jesus was the first congregation of all Haitian women religious. In 1948, Fr. Farnese and Mother Camelia Lohier, the founders, dreamed that the new congregation would serve the poorest of the poor in the remote mountain regions of Haiti. Not much thought was given to financial support at the time, but today that vision is alive and well along with financial struggles. Sisters are teachers, nurses and social workers in places nearly inaccessible. I remember visiting one of their homes for elders in the Jérémie area in west Haiti, and the only way to get there was by small plane.

The sisters are farmers too. They teach women how to garden and preserve food, skills lost when soil deteriorated from erosion, lack of rain and fertilization. The farms supplement to some degree the very limited recompense the sisters receive from their other ministries. Any income is used to help pay for health care of their elders, education, formation of their sisters and support of the ministries for those most in need.

The steady stream of Haitian women joining the Little Sisters and international missionary congregations has mushroomed into a proliferation of new local groups. Since 2009, eight new groups have sprung, bringing the total to 15. They are small, with as few as three to five members, usually recruited by priests or bishops for specific geographical locations.

In spite of their many challenges as a local congregation the Little Sisters have developed many friends in Haiti and beyond. Three Immaculate Heart of Mary Sisters and the Oblate Sisters of Providence of Baltimore have long-standing relationships with them. In general, their partners recognize them as agents of change in Haiti and know they have staying power. They are not going to leave Haiti. Other groups partner with the sisters on small projects and also sponsor children to attend their schools, a popular and much needed contribution. The new partnership with Medicines for Humanity and 11 other congregations has great potential to build a new base in Haiti for collaborative development in health care for the poorest of the poor in the most remote regions. It will also help promote a sense of global sisterhood where working together ensures that no one is left behind.

[Joyce Meyer, PBVM, is international liaison to women religious outside of the United States for Global Sisters Report.]