The city was overrun with sheep. There were herds of sheep everywhere: sheep holding up traffic as they crossed four lanes in a chaotic dash, sheep jostling with vendors on crowded sidewalks, sheep contentedly munching on grass in the median of the highway. Sheep in every direction, in every spare bit of space.

I knew that I was coming to Ethiopia during the Ethiopian Orthodox Christian Holy Week, but I figured, since I was working for a Catholic website and planning to interview Catholic sisters, it wouldn't be a problem to come then — which only goes to illustrate how little I understood about Ethiopia.

"Ethiopia is nothing like the rest of Africa," everyone told me before I traveled to the country for a reporting trip for Global Sisters Report with our international liaison, Presentation Sr. Joyce Meyer. "You will fall in love with the place," they often said. This was the fourth time Meyer was coming to Ethiopia, so it's clearly true.

Christianity in Ethiopia pervades every aspect of the culture and country. This is an ancient Christianity, dating back to the Fourth Century, an Eastern Orthodox Christianity like Russian, Egyptian, Syrian and Greek Orthodoxy.

Approximately 45 percent of the population is Orthodox Christian, while 33 percent are Muslim and a bit less than 20 percent is Protestant, according to CIA World Factbook. Just 0.7 percent of the country is Catholic, yet the Catholic church is the second-largest provider of health and education services, after the government. There are more than 400 Catholic schools throughout the country, educating students of all religions.

Catholicism in Ethiopia is separate and yet inextricably linked to Orthodox Christianity, as we would soon discover. The first surprise was the calendar. Some Catholic churches follow the Latin Rites, celebrating Easter with the majority of the Catholic world on Sunday, March 27. Other Catholic churches follow Ethiopian rites, including prayer in the Ethiopian holy language of Ge'ez and traditional Ethiopian melodies and prayers; those churches follow the Ethiopian Julian calendar, which has 13 months in the year and is currently in the year 2008.

Hence, the sheep. Ethiopian Orthodox Christians and Catholics who follow Ethiopian rites engage in fasting for some 55 days prior to Easter, abstaining from animal products (both meat and dairy) and sometimes avoiding eating before 3 p.m.

The religion might be the healthiest in the world: There are so many fasts, before Christmas and other holidays, including every Wednesday and Friday, that people who follow Ethiopian rites are vegans approximately 280 days per year.

On Good Friday, Christians who follow Ethiopian rites have a seven-hour service, which includes hundreds of repetitions of genuflecting (a kneeling and prostrating procedure). The service is so intense that on the Saturday afterward you can see people limping around the city, recovering from the physical prayer experience.

For Easter, families slaughter a sheep, goat, chicken or cow, or a combination of all four, depending on their economic means. The Saturday evening liturgy before Easter includes hours of candlelit vigils in processions circling each church, looking for Jesus, and at 3 a.m., when the Mass finishes, they can finally eat meat.

Our confusion about religious rites didn't stop with the calendar. Of the 14 dioceses in Ethiopia, we were told, 10 follow Latin rites, which usually means using liturgy similar to that of Roman Catholics around the world. Some of the Latin rite dioceses used the Latin calendar and some used the Ethiopian calendar.

Four dioceses follow Ethiopian rites, which include practices like a curtain separating the priest from the congregation for most of the Mass, and prayer in Ge'ez.

If you've followed us so far, hang in there, because some of the Latin dioceses also pray Latin liturgy in in Ge'ez, while others use the local daily language of Amharic. You could also have an Ethiopian rite Catholic church in a Latin diocese, or a Latin rite church in an Ethiopian diocese, which by the way, isn't called a diocese, but an eparchy.

Also, previously mentioned, the Ethiopian year is 2008 instead of 2016, and "midnight" is marked at sunrise, meaning that 7 a.m. on your watch is actually 1 a.m. Ethiopian time.

After a while, I gave up trying to wrap my head around the differences, and just embraced the experience of being immersed in so much spirituality, with such deep traditions on both the Ethiopian and Latin sides.

I live in Israel, and spent four years in Jerusalem, where spirituality of many different faiths permeates the old stones of the city. I felt the same intense spirituality in Ethiopia. Behind every corner, there are small churches or worship areas. Walking around the city, you can physically sense the deep respect for tradition and a strong sense of identity that comes from thousands of years of existence.

Ethiopia is one of the few places in Africa that was never colonized. The brief Italian occupation from 1935 to 1941 seems to have had little effect on the culture or the country. Part of that is due to the uniqueness and strength of Ethiopia's religious institutions, which have instilled a strong cultural identity across the country, from the big cities to the remote areas.

Here you feel religion everywhere. Orthodox priests stroll through the city with their traditional hats and staffs. Almost every Christian wears some religious symbol, like a cross around his or her neck. At all hours of the day, starting from 3 a.m., prayers from Orthodox churches broadcast on scratchy sound systems roll across the city.

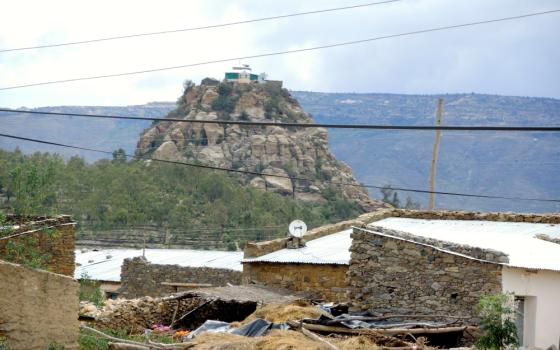

I traveled through the breathtaking vistas of the Simien Mountains, Africa's grand canyon, from Gondar's stone castles to the bustling streets of Addis Ababa, and north to the stark mountains of the Tigray region on the border with Eritrea. I drank more coffee than I've ever had in my life (the personal record was one day with seven cups of fresh-brewed coffee during two separate coffee ceremonies). My shoulders ached from dancing the traditional Ethiopian shoulder dance, since when my few words of Amharic ran out, that was the best way to make friends without language.

I met foreign missionary sisters opening a new convent in a remote mountain village, and missionary sisters who have served for almost 50 years at the same hospital. I met Ethiopian sisters from the south who sometimes felt like foreign missionaries in their own country as they struggled to learn the local language in the north and struggled to understand Ethiopian rites, since they were raised in the Latin tradition. I met a bishop who is worried about how to sustain the local church with local priests and sisters, who have fewer resources than foreign missionaries. I met dozens of Ethiopian sisters who are running schools, eye clinics, empowerment projects, hospitals and much-needed social services across the country.

Ethiopia is unlike the rest of Africa. The people's dress, their food, their language, their identity, their culture and their religion are different from everything I have experienced traveling for GSR these past two years.

After almost a month in Ethiopia, I understand even less than I did at the beginning about the intricate relationship between their religions and rites, their traditions and culture. But it doesn't matter. I fell in love with Ethiopia anyway.

As for the Easter sheep? They were less lucky.

[Melanie Lidman is Middle East and Africa correspondent for Global Sisters Report based in Israel.]