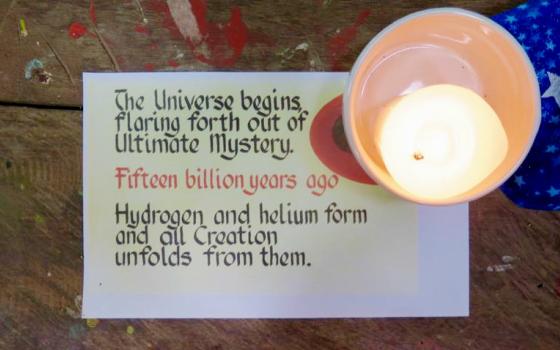

The universe story: We always walk forward. Evolution is always one direction. Sometimes we can go back and visit a point, but it's never the same — we always walk forward in the cosmic journey.

Today, I invite all of us to touch the Earth ... I invite us to walk in intention to carry evolution forward with our bodies and with gratitude.

- Sr. Peg Dillon, Web of Life walking meditation

Wednesday's activities in the Web of Life retreat at the Maryknoll Pastoral Center in Santa Fe began with tai chi at sunrise and a walking meditation, as each headed in his or her own direction. Bird song from the treetops accompanied us as the sun filtered through the trees. And though we started with a somber presentation, as the day progressed, we moved to celebrate a rich abundance of life in many manifestations.

Yolanda Chois, an artist from Cali, Colombia, was in Darién working on a project when she learned the story of five men from Ghana who drowned crossing the Chucunaque River in 2015 as they made their way north to the United States. The five men are buried in a mass grave in Santa Fe.

Their story moved Chois, and she dedicated a year to researching it and documenting it in film and photography. She went to Ghana to track the families down, and she contacted the Maryknoll sisters for help in bringing closure to the case.

On Wednesday, Chois came to the pastoral center with Abdullah Audu Salisu, an artist from Ghana's capital of Accra who had come to see the graves and represent the families of the lost immigrants.

The case illustrates a disturbing trend in the region. Immigrants from Africa and Asia have been making their way up through the Darién Gap, a 62-mile stretch of roadless jungle between Yaviza, Panama, and Turbo, Colombia. Immigrants from South America, Cuba and Haiti have been struggling through the area for years, but what has changed is the demographic: Now, there are more people coming from Africa and the Middle East as the European Union has tightened restrictions and refugees have sought other options.

Chois only could track down the family of one of the five men and learn his story. His name was Toafic Shamu, and he was Muslim, a father of five, in his 40s. He was not in dire straits, but longed for a better life for himself and his family. He was traveling with a group of 30 African immigrants when they crossed the river and became separated, leading to the deaths of the five men.

Chois found their grave under a Christian cross in Santa Fe. With Salisu and another Colombian artist friend, Ana Milena Garzón, Chois planned an intervention. They worked together to design a Muslim-style gravesite, a simple enclosure of stone or cement, and the Maryknoll sisters contributed a tree to place at the gravesite. Meanwhile, Maryknoll Sr. Peg Dillon called the Santa Fe authorities, asking them to remove the trash that had been piled on top of the grave.

The plan was for the Web of Life group to go to the cemetery and pray, but life intervened. We were running late for an appointment with Celsa Grajales, a woman who had fought the government for years for the right to grow a forest on her land, with the support of the Maryknoll sisters from the pastoral center in Santa Fe. It was nothing easy, as the government still has a law on the books saying land has to be under cultivation or it can be taken over by someone else who will cut the trees and cultivate it.

"For some reason, our government doesn't like for trees to be out there, creating oxygen and shade — and the banks that loan the money don't, either," said Horacio Gonzáles, longtime administrator of the pastoral center.

Grajales greeted us with a big bowl of tiny, beautiful cheese empanadas, ginger cookies and handmade sweetbreads with coffee and lemongrass tea. Then we followed her into the forest, which she took over as a nearly treeless ranch and oversaw as it regenerated over the past 30 years.

"First, I will tell you, it's not a primary forest — it's a secondary forest. And it's a forest that, with all modesty aside, I have made," she said as she prepared to lead us down the trail into a jungle that looked as if it had been there forever. "But it hasn't been easy. It's been 30 years of resistance."

In keeping the forest, Grajales was going against the tide, and her neighbors made sure she knew it.

"You need to get in there and clean that up," her neighbors would tell her. The government warned her she needed to start cultivating, but she began a resistance group with the sisters and members of ECODIC, a Christian organization founded by the pastoral center to promote community development and ecologically sustainable sources of income.

Grajales had come here with her then-husband in 1979 to stake a claim. The government was offering 50 hectares (124 acres) to anyone who wanted to come from anywhere in the country to farm the land in Darién, an attempt to mitigate increasing social pressures while dominating the forbidding wilderness.

Grajales and her husband raised five children, and when she and her husband parted ways in the 1980s, they divided the parcel. She and the children ended up with half.

Surrounded by cattle ranches, Grajales grew a jungle. She also began cultivating medicinal plants, a skill that served the pastoral center well when they launched the community development program ECODIC. Grajales was one of the founders.

"For a long time, she had to listen to her neighbors laughing at her. 'Oh yes, you're the one who won't cut her jungle,' " Gonzáles said.

Grajales said her greatest accomplishment, besides the forest itself, is a 16-foot-deep well she dug with her own hands. The water is too mineralized to drink, but it waters the animals and the plants.

Grajales is proud beyond words as she leads the troop of international visitors through her land, past a massive cuipo tree that is home to the famed harpy eagle, past a fig tree that is food to whole flocks of birds and animals, and past dozens of colorful mushrooms of different varieties. Not long ago, she led a researcher from the University of Panama and one from the United States who marveled at the variety of fungus they found here.

Grajales' Panama tree could bring in some much-needed cash for its lumber, but she isn't tempted in the least, and she beams as she poses with it for a photo. Some plants are grand, while others are tiny and subtle, she says, but that doesn't make them any less important than the big ones. Indeed, I sense that much of what one sees here in the hot, moist air of the Panamanian rainforest is almost at the subconscious level.

All a part of the great cosmic dance, I thought.

Back at the pastoral center, this day ended not with a circle of reflection, not with a prayer, but with a dance. It was our last night in Darién, and the people wanted to celebrate with merriment.

"There's an old Catholic saying: 'They who sing pray twice,' " said David Molineaux, a Web of Life retreatant. "So they who dance pray thrice."

Bodies twirled in the dim light of the dining hall under a globe of the blue Earth draped with twinkling green lights, and laughter rang out with the insistent bass of a hand drum and the tinkle of a tambourine.

The stereo vibrated with a peppy selection of rock 'n' roll and pop music. Dancers drew in resisters until everyone was on the floor. The sisters were in the middle of the circle, singing and laughing and dancing, and it was good to see. Then the smiling voice of Molineaux, a teacher of Biodanza, rang out as the beat slowed to a gentle classical tune.

"En la danza, como en la vida, hay que fluir," he told us. "In dance, as in life, one must flow. You are invited to let go ... relax your shoulders, your arms, your knees a little bit, and what I'm going to invite you to do stretch to the maximum in all directions with this music. ... Then flow. You are water. You are air."

And so it was, as a dozen points on the Web of Life flowed together and vibrated with joy in the dim light of the dining hall.

[Tracy L. Barnett is an independent writer, editor and photographer specializing in environmental issues, indigenous rights and sustainable travel.]