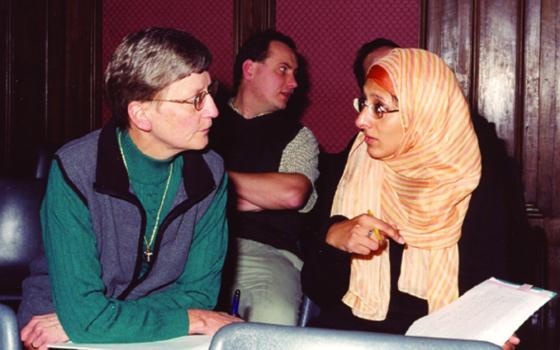

When Sr. Kathleen Warren of the Sisters of St. Francis of Rochester, Minnesota, began a master's program in Franciscan spirituality and Christian-Muslim dialogue at St. Bonaventure University in 2000, she could not have imagined what the next year would bring.

After 9/11, Warren said, "the whole world was going to be involved in trying to figure out what is the huge conflict between Muslims and Christians."

Warren followed her master's with a Doctor of Ministry from Graduate Theological Foundation. She's also been instrumental in the creation of two films ("In the Footprints of Francis and the Sultan: A Model for Peacemaking" in 2013 and "The Sultan and the Saint" in 2016) that depict the meeting between St. Francis and the sultan of Egypt during the Fifth Crusade.

Warren spoke to Global Sisters Report about the Catholic roots of interreligious dialogue and why that dialogue is so important in the face of rising Islamophobia.

GSR: Dialogue is a word people use a lot in interfaith settings. Can you tell me what it actually means? What does dialogue look like on a practical level?

Warren: Well, there's a wonderful document, "Dialogue and Mission," that has come out by our Roman Catholic Church that identifies different kinds of dialogue. When we talk about interreligious dialogue, many people think about needing to have theological discussions with people and defending one's own doctrine against another religion's doctrine. [She laughs.] And that is not at all what the understanding of dialogue is really all about, even as articulated by the Catholic Church.

There are different kinds of dialogue, and possibly the most important is simply the dialogue of life. For instance, birthday parties, backyard picnics in the summertime — those kinds of things that are just the essence of daily life. So there's the dialogue of life, which is very important and fundamental.

There's also the dialogue of religious experience: maybe a Catholic family inviting their neighbors to a first Communion and a Muslim inviting a Catholic family to a breaking of the fast during Ramadan; a Muslim inviting a Catholic family to a Friday prayer service in the mosque and then attending a Catholic Mass in the church. Those kinds of dialogues of religious experiences are also very, very important.

And then there's also the dialogue of action — something like Habitat for Humanity or working at a soup kitchen. Doing those kinds of things together and realizing that deep in our hearts, we all want to be about the betterment of the lives of other people.

And, yes, the theological dialogue is important, but that's really reserved for those who are the scholars or the educators in each of the respective faiths. But it's not for the sake of trying to convince the other person that they might want to consider changing their religion; it's simply to explain what it is that one believes and why one believes that. And the result, by and large, when there's real, authentic dialogue going on, what we find out is that we do have a deeper understanding of our own faith. We can have a very great respect for another religious tradition even while we know our home continues to be in our original religion.

What has that looked like in your life?

As I have heard people from other religions — mostly it is interaction with Muslims, although I've certainly interacted with all the major world religions — but when I do this kind of discussion, I'm always inspired by the way in which other people talk about their faith and the depth of their own belief in their faith. As I listen to other people speak from their own unique perspective and their own religious tradition, I realize the pearl that I have in my own faith, and I see new nuances for my own living of my faith in the world, the choices I make and how they're linked to what I believe about my relationship with my God.

Have you ever received any criticism for that?

I have been confronted with some statements and some challenges that tell me that I am not representing the true Catholic teaching on Islam. But what the Second Vatican Council has articulated for us in the powerful document Nostra Aetate is that it's not optional for us to be engaged with other world religions — it's our obligation to be in dialogue with people of other faith traditions, to respect those traditions and to find ways of working together with members of those faiths.

Do you think interreligious dialogue, particularly with Muslims, is more important today because of some of the attitudes about Islam?

Oh, yes. Absolutely. It's no surprise to anyone who reads papers or listens to the news that Islamophobia is on the rise. Racism, bigotry, xenophobia are all on the rise in our country and in many places in the world. And it's most likely not going to be stopped by any kind of laws or rules. It's going to be stopped when people start speaking up and when people say, "I will not be a part of this kind of a conversation."

I think the marches that are going on in our country are speaking to that. People are finding their voice in so many ways that has not happened in the past. And it's essential that we encourage each other to be about speaking that voice.

Who in your opinion is doing interfaith dialogue well?

In local settings, there are a number of different interfaith groups that have put themselves together — and these aren't going to be anything on the national level that would carry over, and maybe that's the best way. It's the grassroots initiatives in various places. There's one group here in San Diego that's organized by a Baha'i couple. People from all the different religions gather to focus on prayer and the way in which their religion is challenging them to live out their faith in the world.

In Cincinnati, Ohio, there was a parish that invited Muslims and Christians to come together for a six-week session, and every week they identified a topic: How do you pray? What are our holy days? What do you believe about war? Where are our pilgrimage sites? It brought out the commonality of the human condition in terms of what we long for, what our gifts are and what we really most desire.

I'm sure this could actually be a book, but what lessons do you think people can take from St. Francis' meeting with the sultan of Egypt?

[She laughs.] You're right; that's a book. I do weeklong retreats on that. But it's all about, first of all, just believing in the presence of God in each person. We all have the same God Creator, and we are all on a journey returning to the same God Creator. We are all children of God and, therefore, brothers and sisters of each other. We're endowed with gifts and powers freely given us by this gracious God and are meant to make this world more reflective of the God who has made us — or as St. Francis came to understand, we are meant to be about the rebuilding of the house of God.

[Dawn Araujo-Hawkins is a Global Sisters Report staff writer. Her email address is daraujo@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter: @dawn_cherie.]