Eighty-three-year-old Sr. Cora Richardson was brought up at Rossduff House in County Waterford, Ireland, the youngest of four girls and two boys.

Schooled by the Brigidine Sisters from 1945 to 1951, she spent a year at finishing school in Brussels before she attended University College Dublin, where she studied law and history.

Prior to retiring to Ireland four years ago, Richardson spent most of her 50 years as a missionary in South Africa, where she challenged apartheid and met Nelson Mandela and Steve Biko. Despite her age, she continues to speak up for what she believes in, including women priests.

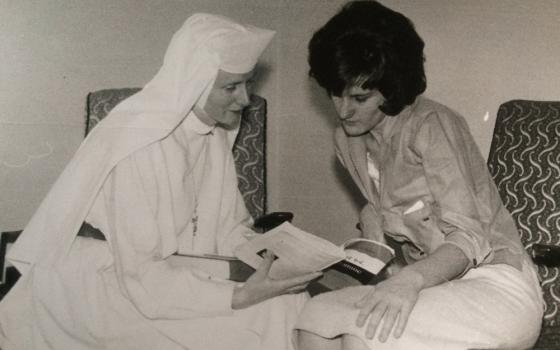

She spoke to GSR at her Dublin convent and began by recalling leaving her boyfriend behind in 1956 to join the Missionary Sisters of the Holy Rosary in Killeshandra in County Cavan.

Richardson: It was the hardest thing I ever did. As I was driving from my home in my little car, accompanied by my father and my sister, I stopped along the way to make one last telephone call to say farewell to him. Afterward, I prayed and prayed that he would marry a nice lady, and he did.

I entered in 1956 and was professed at the end of 1958. I was sent out to South Africa in February 1959. To my disappointment, I was put in a white high school. After a few years, I said to the regional superior that I hadn't entered to teach white wealthy children in a white high school, and if I didn't get into African work, I would leave the congregation because that was my vocation and call.

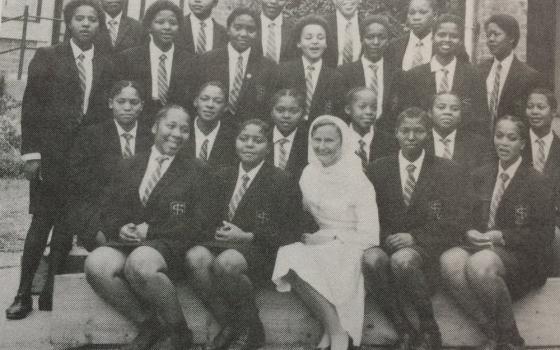

People didn't agree with me. They thought I was a black radical, as one sister put it. I later taught English to African students at Inanda Seminary in KwaZulu-Natal and at an African boys' high school in Khwevha, Sibasa, in northern Transvaal.

GSR: Thanks to your studies in law, you were well informed about people's rights, but the search for justice had consequences.

I was always in trouble with the white government, and I was interrogated while I was in Sibasa. One fellow who came to the convent accused me of being a communist, but I replied that I couldn't be a communist because I was a Catholic, and a Catholic can't be a communist! He said he would close down the mission and the sisters would all be sent back to Ireland and it was my fault. He was trying to intimidate me. He believed we shouldn't be helping the African people to get their rights. I found out afterward that he had left out that his name was Trotsky.

How did institutionalized apartheid impact on you while you were teaching?

At the boys' high school in Sibasa, the principal was white, and there were a few white teachers. The rest were African. There were two separate tea rooms for the teachers, and even when we prayed, we stood separately. But I stood with the African teachers and had my tea in their room. The principal didn't like that. Once, he called me into his office about it. I told him that it was an African country and change was coming. He opened his briefcase and took out a revolver and told me, "We will die with our back to the wall."

The white people thought change would never happen. If you have your foot on the neck of somebody all the time, you are always afraid that they are going to throw you off and walk on your neck. There were some wonderful Afrikaans people, but on the whole, and perhaps among the less educated, they were scared, and so they had to keep the lid on the pot before it boiled over. The wonderful miracle was Mandela and what happened — we got change with peace, but a lot of people died before we got it.

In 1989, you returned to Ireland to take up the role of congregational secretary at the generalate in Dublin. Then you got a phone call that would bring you back to South Africa.

In 1993, I got a phone call from England, asking me if I would act as a monitor for EMPSA — the Ecumenical Monitoring Program on South Africa — as there was violence there. I got the general council's permission and went to South Africa.

Chris Hani was murdered, shot in Dawn Park in April 1993 by a Polish man who was with a South African white man. People were worried that the violence would escalate. I volunteered along with a Finnish woman who was one of the EMPSA team to go to Dawn Park, which is a township, to monitor the violence. When we got there, we found a dead body on the ground and asked that the man would not be left lying there with no dignity.

There were hundreds of Africans marching up the road, and white soldiers appeared with their guns and stood in front of the Finnish monitor and me and Sr. Sheelagh Waspe. They told us to part. We were standing there to protect the people coming up the road because they were going to be shot. We wouldn't move. So the soldiers got down on their knees in a line, and we heard this click; they had their guns primed. I said in Afrikaans, "We want to see your commander." The commander came and gave an order, and just like that, the soldiers' guns were at their sides, and so bloodshed was probably prevented.

The 1994 election saw you back in South Africa monitoring the voting.

I had been asked by the congregation when I first arrived in 1959 to become a South African citizen, but I refused. I said I wouldn't become a citizen as long as the black people of the country weren't allowed to be citizens. It was wonderful to see people able to exercise their vote in 1994.

What are your thoughts about South Africa today? Are you hopeful for the future?

There is a bad man in charge, President [Jacob] Zuma — he was a crook before they put him in. I am hopeful for the future because the people are good basically, but all of Africa is in turmoil. Look at Zimbabwe next door, [Prime Minister Robert] Mugabe is a dreadful man, worse than Zuma. He is no credit to his Catholic education.

When you returned to South Africa after six years on the generalate and a sabbatical studying contextual theology in Berkeley, California, you got involved in anti-trafficking projects in South Africa. You continue to be involved in this issue in Ireland through Act to Prevent Trafficking, an initiative of some Irish religious congregations. Another issue you got involved in while in South Africa was women's ordination.

I believe there will be women priests. It is only a question of time. The Lord is calling women to priesthood. The Holy Spirit is telling the church what to do — it is as clear as daylight if you open your eyes to see. Pope Francis sees it, but he is also meeting opposition from the people around him, and he may be worried the issue might cause a schism in the church. Our Lord had women around him all the time, and he made Mary Magdalene the apostle to the apostles. I am really sorry for those men who have such a problem with sexuality and with women that they fear change.

You seem undaunted by the possibility that the Vatican could censure you for expressing such views.

I love the church, and if I am put out of the church by the Vatican or a bishop, I will stay Catholic in my heart. A lot of people are fearful of change. I don't know if it is a question of power and control. But there are women who feel called to priesthood. St. Therese said she would wish to be a priest.

I don't feel called myself. I always desired to be a missionary, and the Holy Rosary Sisters' calling is purely missionary. Our founder, Bishop Joseph Shanahan, said that we were meant to be missionaries and not to be at home teaching, as there were other people to do that. We go somewhere, and we help, and then we pass it on to the local people.

What kind of changes are the Missionary Sisters of the Holy Rosary seeing these days?

We, the Irish sisters, are getting older. We haven't had any young Irish women join now for a long time, but we have a lot of African sisters from many different countries. In the latest intake, there was an Ethiopian, a few Cameroonians, a Nigerian, a Ugandan and some Kenyans — wonderful. Bishop Shanahan used to pray, "Lord, that I may see," by which he meant that as I look at you, I see Jesus. No matter what color or how old or young or how ill you are, God is present in you — and that is awesome!

[Sarah Mac Donald is a freelance journalist based in Dublin.]