School Sister of Notre Dame Kieran Sawyer has been involved in sex education since the 1970s, first as a teacher creating and sharing her popular lesson plans then writing programs for other teachers and catechists.

For decades, her lesson plans have been based on what she calls a L.I.F.E. structure: Love, infatuation, friendship and exploitation are four areas she defines for her students while they interpret what it means when those areas overlap.

For Sawyer, sex education means teaching children about loving relationships. They learn about family love and friendship as young children, she said, but once they hit puberty, they have to learn how to integrate their sexuality into the process of learning to love and learn to identify the subtleties of abusive relationships.

"I have found that teens listen to language about 'using' much more readily than they listen to language about sin," Sawyer said. "That structure, just those four concepts, have been the basis of many good lessons I've done with teens, and I've developed it in all kinds of ways," ways she has shared with other teachers who have had success with this approach.

In conversation with Global Sisters Report, Sawyer talks about what those classroom discussions look like, the programs she's currently creating, and why the church needs to step up in helping parents have these tough conversations.

GSR: What's one of the more popular classroom activities that students respond well to?

Sawyer: Say I'm teaching a group of 15-year-olds the L.I.F.E. structure. I say, "Let's talk about the relationship I call the big IF — the combination of infatuation and friendship. If some things go on in that relationship, it will grow toward love, and if other things go on, it has a big chance of moving toward exploitation."

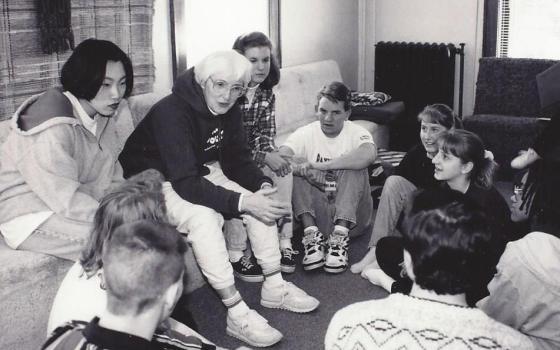

So then I have 30 question cards, all starting with the question "What if?" and there are groups of kids with a group leader. They draw a card and read it; it says, "What if most of the time, when the couple is together, either one or both of them is drunk or high?" Will that relationship go toward love, or is it likely to turn into exploitation? And the kids decide together as a group to put it under the E on the L.I.F.E. chart.

Or: "What if this relationship makes me more open to other people and more caring toward my parents and my brothers and sisters?" The teens can easily see that one pointing toward love.

(The seventh- and eighth-graders know right away. And I've done it with college kids, and they argue about every question, because relationships are so subtle, the way E gets in there.)

That's a little tool, of having cards in the kids' hands — everybody is paying attention, and they're making their own decisions. I don't tell them the answers; they tell themselves the answers.

Sometimes, they'll say, "Sister, you never tell us what you think." If they ask, I tell them what I think, but I have to be cautious. It's not what I say that matters; it's what the kids hear that matters. If I say something that means one thing, they can hear it from where they are. I may give a different answer to an adult group than I would to a teen group because teens are so black-and-white in their thinking, and I don't want to give them permission to do things that will be harmful to them. I'm trying to get their minds open and get them to realize they have to make their own choices. I can't make their choices for them. Neither can their parents. It's one of my biggies: You are in charge of you.

Have responses from the students' end changed over the years?

Actually, no. Kids are kids. The kids I'm dealing with are just the way you were when you were that age. Every teenager wants to be loved. The boys experience their sexuality being aroused, but they don't know it's not love. The girls are pretty sure it's not love, but they like the attention. That's not different from when you were 15 or 17.

What's different today is the amount of negative messages the teens hear, the absolute "of course everybody is doing it" message that says, "Sex is fun, so let's go do it."

Figuring out who they are and what they want to do in their life and how they're going to use this huge energy they have in them to be sexual, that's forever-stuff. It's what it means to be a human being. To explain that in a way where they listen to me — that's the challenge of doing good catechesis.

Are there obstacles to teaching sex ed as a chaste woman? Do you address that in the classroom?

I don't think my vow of celibacy disqualifies me as a sex ed teacher at all. I want the teens to understand that falling in love — infatuation — is not the same as loving. Infatuation is a feeling; love is a commitment.

Every person needs to learn how to practice chastity, the virtue that directs our sexual feelings and desires toward loving someone and away from using them. I've often spoken to teens about celibate love, a term I prefer to chastity. Some people, I tell them, promise God that they will be celibate in all of their love relationships so they can be free to serve God and his people. That doesn't mean that they won't experience sexual attraction. I have had many male friends over my long years as a nun, people I have loved and still love deeply.

I like to tell teens that even married people take a vow of celibacy. The marriage vows imply that the couple will be celibate in every relationship except one: their sexual relationship with one another. Rather than talk about abstinence, I ask the young people to make a temporary vow of celibacy, promising God that they will be celibate in every romantic relationship until they are ready to give their entire life to one person, either to God or to their marriage partner.

You told me you're writing lesson plans for other people to teach about sex, including two new programs. What are those new programs?

Recently, I've been spending a lot of time on two programs: LoveEd and Learning about L.I.F.E. Both are designed to help parents talk to their own children about sexuality and other important life realities. And both are based on the conviction that teaching children about sex is really teaching them about love.

I was the catechetical consultant for LoveEd, a video-discussion program by Coleen Kelly Mast, which guides parents in talking to their own children about both the biology and the theology of puberty and sexuality. And I'm currently working with Kathie Amidei to revise and expand the L.I.F.E. program, which we wrote 10 years ago in response to the sex abuse crisis.

The revision calls for a parish gathering of parents with their own children at each grade from kindergarten through high school. In these sessions, a facilitator guides the families in discussing the three kinds of loving relationships — family love, friendship, and infatuation — and the ever-present possibility of exploitation in each of them. These discussions are always engaging and age-appropriate.

You promote the concept that parents should take on sexuality and chastity education but that the church needs to be more helpful in this realm. In what ways has the church failed to fulfill that role? What do you suggest the church do?

The church has produced wonderful documents about sex education over the years, but I feel we have done very little to show people how to live those teachings. The documents call sex ed "education for love" and say that the parents are to be the primary educators, but little has been done to prepare parents for this role. That's why I would like to see our new lesson plans in every parish. We want to help the parents with this important job.

I'm encouraged by the wonderful response that Pope Francis is getting to Amoris Laetitia, which has a whole chapter on chastity education. I'm really hopeful that the church will listen to Francis, and maybe we'll get some good sex education going. Maybe even the L.I.F.E. program, which is designed to teach parents and children how to create loving families.

[Soli Salgado is a staff writer for Global Sisters Report. Her email address is ssalgado@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter: @soli_salgado.]