For Sr. Pilar Chagoya Mingüer, co-founder of the new Diocesan Social Pastoral School in the city of Oaxaca, Mexico, these are times of healing after a long and difficult era that saw former archbishop José Luis Chávez Botello step down in 2016 amid a sexual abuse scandal, blamed for covering for pedophile priests accused of abusing indigenous children.

Pope Francis' new appointee, Archbishop Pedro Vázquez Villalobos, took office in February 2018, inheriting an institution fractured by scandal and discord, but his first year at the head of the Oaxaca Diocese gives Chagoya much reason for optimism.

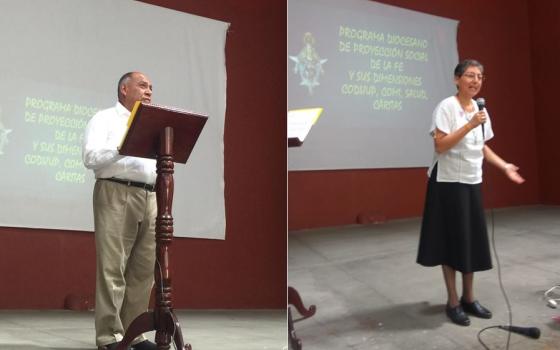

Previous administrations over the past two decades gave social programs low priority. Chagoya, a practicing dentist, licensed attorney and longtime advocate for social justice, teamed up with Fr. Lionel Cárdenas three years ago in the Social Projection of Faith Program, organizing different activities to try and promote interest in the program. The Social Projection of the Faith Program is an umbrella for all the social programs in the church, including CODIJUP (Justice and Peace Commission), COMI (Mobility Commission, for assisting migrants), Salud (Health) and Caritas. The Social Pastoral School was launched under the auspices of the Social Projection of the Faith program.

In November 2018, during the diocesan assembly for parish priests, sisters and pastoral agents in the diocese, the need for comprehensive education was identified as a priority. That's when Chagoya and Cárdenas' plan for the Social Pastoral School was presented — an initiative to restore what Chagoya says is the rightful duty of the church and its members to actively work for justice and the well-being of people who live in poverty.

In February, the Diocesan Social Pastoral School began to teach and motivate faith leaders throughout the Archdiocese of Antequera, Oaxaca, to take on projects in the areas of migration, food sovereignty, health care advocacy and strategies for empowerment of marginalized communities. The weekly lessons, which ended Aug. 24, drew around 130 faith leaders on a weekly basis.

I sat down with Chagoya in the simple but welcoming home in Oaxaca City that she shares with four other sisters of the missionary congregation Servants of the Holy Spirit (Misionera Sierva del Espíritu Santo).

GSR: Tell me a little, please, about the challenges that religious sisters in Oaxaca faced under Archbishop José Luis Chávez Botello.

Chagoya: That time was very difficult for those in consecrated life. Several congregations left the archdiocese; only the sisters dedicated to education and those attending the hospital were left. Three or four congregations that work in the communities stayed, but with much difficulty. Now we have a new archbishop, and he asks us for forgiveness. But really, here in Oaxaca, in consecrated life, we have entered into a disarticulation.

We are seeing that each congregation does what it has to do: Those who have schools stay in their schools; those who have hospitals stay in their hospitals. Those who are inserted in communities stick to their parishes. And if the priest treats you badly, it's your problem. In other words, there's no cohesion among us.

So now with the new archbishop, have things started to change?

Yes, now there's Mr. Pedro Vázquez Villalobos. To me, he's a beautiful person, and that has been the experience of the religious where he has gone. Since he's moved to the archdiocese, it's been a very good experience. He's very close, not only with the religious but with the people. He's very much a pastor, and that has allowed us from the social pastoral mission to carry out our projects, and he supports us.

As a religious, I am collaborating in an area that was previously inactive, and now, with Father Lionel, we are working in an articulated way. It has not been easy. Little by little, we got to know each other, and we had some disagreements. Something that has helped us is that the service that he and I do is for the church, and who is the church? The people. I am working neither for the bishop nor for the priest, but for the people.

Before, I was the coordinator of justice and peace of my congregation, and my sisters all knew what justice is, what peace is, that we all have to be promoters of caring for the environment. Because that's the task of our congregation within communities.

First, we dedicated ourselves to the task of explaining what the social pastoral program was, because the pastoral leaders generally think of it only in terms of handouts: "I'll give you some food, together with a little money, and you'll take it." But for social issues that sometimes involve denouncing or taking a stance — it's not done, because they say, "That doesn't concern us." Of course it does.

So we have been organizing training workshops. A food sovereignty workshop was held, and during the elections, we had the faith and politics workshop, which brought us some difficulties among the priests.

The social aspect isn't a separate thing. The social aspect impregnates the entire mission; it's an evangelizing process, a catechesis, and it has to start from the social to lead to the social. If not, you receive the sacrament, and that's the end of it.

That's the idea that prompted us to start this school.

That's what we are doing now at the level of the archdiocese. Right now, there's a document that's a global plan resulting from the pastoral reflection of the bishops of Mexico. This document talks about families, about young people, native people, about women and their role within the church. Then it was mentioned that it's necessary to include women in decision-making.

So this is a very interesting new project, right?

Yes, well, we are excited. We are working on the Social Projection of Faith Program and its dimensions: There's the justice and peace dimension, the hospital or health pastoral, human mobility, and Caritas, which is a commitment we have assumed. The one who is very close to that is Fr. Martín Octavio García Ortiz, the archdiocese's justice and peace coordinator. As a part of his responsibilities, he is in charge of two lawyers. They give legal advice to local communities when there is a territorial conflict.

Like when there's a hydroelectric dam or something like that?

When they are defending their territory, yes. They are also in charge of giving information about megaprojects; for example, the construction of dams, mines, etc.

Also, the graduates must be prepared to respond to requests for medicines in the communities they visit; for that, we contact Fr. Francisco Silencio, who coordinates the hospital pastoral and finds a way to provide the medicine.

Do you think that Archbishop Pedro is going to support you in terms of social concerns?

Yes, he is supporting us a lot with his closeness as pastor. He is attentive and cares about the pastoral work we are doing. We count on his moral and economic support at certain times. But the Social Projection of the Faith Program has no income to help us pay for the expenses that arise. We just trust God will provide in the case of the pastoral school. A small store was set up to cover some of the expenses we generate to make copies of the materials that students need, to borrow the room, and so forth. It's the way we've been working so far.

It seems that things are changing.

Yes, yes. There's a lot of hope. I am excited, I am happy. Reaching this level has taken us a lot of effort. Yes, we have had difficulties; we had to balance, talk, give our point of view. But right now, we can say that we already have gone a part of the way.

You have had to make a space for yourselves.

Yes. My character has influenced many things, as my training was very strong. My first trainers were from the United States, Argentina, Brazil, India, but when I was on the Oaxacan coast [in the late 1990s], I had some sisters from Brazil and Argentina who were very radical in terms of poverty. You accompany the people, you do what the people do. Why are we going to pay for a truck if the people don't have money to pay? Let's walk.

Those sisters were very, very strong, so that stuck with me a lot, and sometimes they tell me, "Sister, it's just that your training is very strong. You're very strict." It's simple: I commit, or I don't commit. For me, it's a choice for life. I made a choice to be a religious. The Lord invited me, and I gave an answer from the limitations that I have as a human, of character, of complexes, of weak points — but God provides.

[Tracy L. Barnett is an independent writer, editor and photographer specializing in environmental issues, indigenous rights and sustainable travel.]