From left, Esther Ruth Modonig, Martha Akoul and Sarah Yar are high school students at St. Mary Assumpta Girls Secondary School near Adjumani, run by the Missionary Sisters of Mary Mother of the Church. They are leaders of the South Sudanese students group. (GSR photo / Melanie Lidman)

Reflect on your own or with a partner on the following questions. These will help you to connect with the story you're about to read.

- Think about a time when you've been an outsider within a new place or group, or just a time you haven't been sure where you belong. How did that feel?

- Why do you think people generally leave their homes to come to a new place?

- In general, how have the Ugandans treated the refugees from South Sudan?

- Why have they had this attitude?

Seeking Refuge: Ugandans, displaced once themselves, welcome South Sudan refugees

Some days, Angelika Ouma isn't even sure which side of the border she's on.

"I was born in Sudan, then I came here [to Uganda] when the situation was bad, then I went back to Sudan when it was bad in Uganda, and now I'm back here," said the 73-year-old nursery school teacher.

Over 60 years, Ouma has crisscrossed the border in pursuit of a peaceful place to teach children. She completed primary school in Uganda but returned to Sudan for higher education. Escaping violence in Sudan, she first worked as a nursery school teacher in Uganda, where she met her husband. Together, they fled to South Sudan when northern Uganda was unsafe. Ouma finished her career and retired, expecting to relax in South Sudan. But, suddenly, after fighting broke out in her village, she found herself, now widowed, once again escaping across the border.

Now, along with the Missionary Sisters of Mary Mother of the Church, she helps coordinate nursery school classes for more than 70 South Sudanese refugees from her community in Kocoa village in northern Uganda. Refugees make up about a quarter of the students at the Bishop Caesar Asili Memorial Nursery and Primary School.

In addition, a small percentage of South Sudanese refugees who were able to secure scholarships at schools outside the settlements have been absorbed into regular classes with Ugandans.

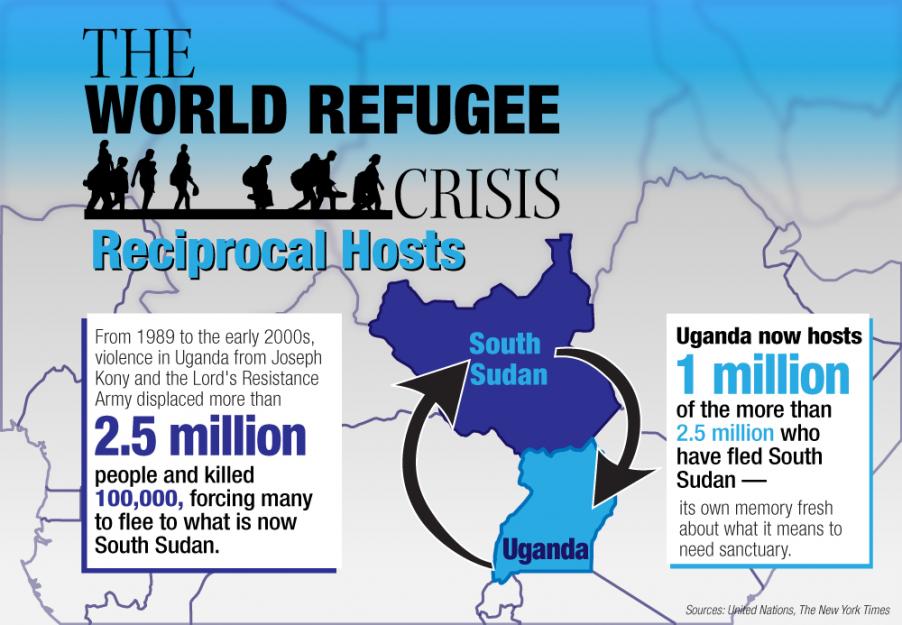

As countries around the world try to deal with waves of refugees flooding their borders, Uganda has quietly accepted a million South Sudanese refugees, almost half of the more than 2.5 million people who have fled South Sudan since 2014, according to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees. Today, the country absorbs an average of 500 refugees from South Sudan per week, which is considered a quiet period. At times, 1,000 children were fleeing South Sudan every day.

This has made Uganda, in the course of just a few years, the African nation with the largest refugee population and one of the top five host nations in the world.

The country also hosts almost 250,000 refugees from the Democratic Republic of Congo and more than 70,000 refugees from Burundi and Somalia, according to 2017 U.N. data.

Although there are significant challenges, and many refugees living in settlements complain of issues with security and sanitation, Uganda's attitude toward refugees is considered more accepting than many other countries.

Uganda has "one of the most open refugee policies in Africa, and most likely in the world," U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi told reporters after visiting the Imvepi Refugee Settlement in Uganda.

That's partly because the memory of being a refugee is still fresh for many people in northern Uganda, where the majority of settlements are located.

Starting in 1989, Joseph Kony, a self-described prophet bent on overthrowing Uganda's longtime president, Yoweri Museveni, instructed his followers to kidnap children as young as 8. His plan was to brainwash them and force them to burn down homes and rape and kill their neighbors. The violence displaced more than 2.5 million people in northern Uganda and left 100,000 people dead. Kony and his guerrilla group kidnapped more than 30,000 children and forced them to commit atrocities during two decades of war.

Kony's group, the Lord's Resistance Army eventually crumbled, and the war ended in the 2000s. Despite international attempts to capture Kony, he fled to Sudan or the Central African Republic with a small group of supporters and is still on the run.

Angelika Ouma, left, the director of the Bishop Caesar Asili Memorial Nursery and Primary School, and head teacher Sr. Laura Kaneyo sit outside the school, overseeing an expansion that will enable them to open an additional classroom. (GSR photo / Melanie Lidman)

Even though most of the students are on break, the house mother, right, at the Bishop Caesar Asili Memorial Nursery and Primary School prepares lunch for some of the South Sudanese students who might not otherwise get enough to eat during the school vacation. (GSR photo / Melanie Lidman)

Northern Uganda began to emerge from the years of terror. Those who had fled their villages — many to the part of Sudan that became South Sudan after it gained independence in 2011 — returned. Religious leaders oversaw traditional forgiveness ceremonies to try to heal the communities' wounds. Sisters and educators created special training and educational opportunities for returning child soldiers to help them integrate. With time, these traumatized children became community leaders and advocates for peace.

Farmers planted crops in land that had previously been abandoned. Gulu, the regional capital, started growing at a breakneck speed, with a network of newly paved roads linking it to other cities in the region.

Then civil war broke out in South Sudan in December 2013. Before long, hundreds of thousands of South Sudanese began to flee across the border to Uganda's relative stability.

"There's a culture here in Uganda of welcoming," explained Sr. Helen Tabea, a member of the Evangelizing Sisters of Mary from Uganda, and an English teacher and program coordinator with the Jesuit Refugee Service in Uganda. "And the fact that Ugandans have experienced difficult times for a long time, we remember what it's like. The South Sudanese and the northern Ugandans are basically cousins. They speak the same language."

Jesuit Fr. Kevin White, the country director of the refugee service, says Uganda has an excellent refugee law today "and it's because they have a live memory of when they themselves were refugees."

The government of Uganda is careful to refer to refugee "settlements," not "camps." Every few months, it builds a new settlement, which quickly fills to capacity. Bidi Bidi, now considered the world's largest refugee settlement with almost 250,000 people, opened in August 2016 and was filled by December.

Refugees in Uganda can move freely about the country and obtain work permits. Most are assigned a 30-meter-by-30-meter (about a 10,000-square-foot) plot of land in a settlement, where they are encouraged to build their own homes, dig a pit latrine and grow some of their own food in an effort to encourage self-sufficiency and promote dignity. This also lessens a common side effect of refugee camps in rural places around the world: soaring inflation for the local population when refugees are given cash by international nongovernmental organizations.

"The humanitarian response about Uganda has been quiet because Uganda is doing a good job. You only get attention when it bleeds."

—Fr. Kevin White, Jesuit Refugee Services, Uganda

Refugees in Uganda can move freely about the country and obtain work permits. Most are assigned a 30-meter-by-30-meter (about a 10,000-square-foot) plot of land in a settlement, where they are encouraged to build their own homes, dig a pit latrine and grow some of their own food in an effort to encourage self-sufficiency and promote dignity. This also lessens a common side effect of refugee camps in rural places around the world: soaring inflation for the local population when refugees are given cash by international nongovernmental organizations.

In some parts of northern Uganda, refugees will soon outnumber Ugandan citizens, as the country was on track to absorb an additional 400,000 refugees during 2018. In 2016, the region of Adjumani had 170,000 refugees and 210,000 Ugandan citizens. Land is quickly running out, and refugees who come these days might only receive a 10-meter-by-10-meter plot of land, which will not be enough to grow their own food.

There is not enough water in the area to support such a large population, and trucking in water has become too expensive. Trees are disappearing as people cut them for firewood.

For now, Ugandans have been welcoming their South Sudanese neighbors, but as competition for resources increases, this goodwill may disappear.

Tabea said the plots that encourage refugees to grow their own food are essential to maintaining good relations between the refugees and the local population. "[Refugees] must stand up on their own, and people do," she said. "People start working, or they sell small items. Uganda doesn't have a lot of resources, but we do have very rich soil. Within two weeks, you can have vegetables, and within a month, you can have beans if the rains cooperate."

(GSR graphic / Toni-Ann Ortiz)

'We've always had wars around here'

Sisters in northern Uganda have had to quickly adapt their ministries for a changing population, especially those working in education.

Yet, despite the severity of the South Sudan refuge problem, the changes at schools and ministries were not drastic. Many of the sisters were already working with Ugandan refugees who were starting to return, so they were familiar with the traumas refugees face.

If the walls could talk at the Bishop Caesar Asili Memorial Nursery and Primary School, they would tell the history of a broken region. The building was originally built for the Missionary Sisters of Mary Mother of the Church, but in 1992 rebels from the Lord's Resistance Army broke into the compound, killed a watchman and kidnapped a sister, who was later rescued. The congregation left the area and moved south to safer parts of Uganda. Sudanese seminarians from the Comboni congregation moved in but then went back to South Sudan.

The sisters began returning to the area over the last decade, first re-establishing a health center and maternity lab. The school opened in early 2017 as a nursery and primary school. Refugees make up about a quarter of the enrollment.

"The refugee children have a different character from the children here. They have wild behavior because they are traumatized," said Sr. Laura Kaneyo, the head teacher.

She said the children are often fighting. "They were born in the war, they grew up in the war, they don't know peace," she said. "Without a big heart, you cannot handle this group of people; you must have patience and tolerance."

Kaneyo depends on people like Angelika Ouma, the kindergarten teacher who was a pillar of her community in Nimule, South Sudan. When Ouma fled to Uganda in the current round of fighting, many families followed her to Adjumani so they could enroll in her school again.

Ouma looks out over her students, a dozen rowdy boys of varying ages who are at the school even though it is vacation time, because there is nothing to do at the settlement. They gather to sing traditional Madi songs for a guest and then help the school's "mama" cook lunch.

Sitting in a plastic chair, Ouma watches as workers put the finishing touches on an expansion to the school that will allow it to open another classroom and serve more children, both Ugandan and South Sudanese.

She doesn't know which side of the border she will end up on or if she will live to see peace. Like many South Sudanese refugees, she longs for a day when she can return "home," to South Sudan, even though she has spent more than half of her life in Uganda. But she also knows how to provide stability for her main concern, the children under her care, despite the uncertainty of their future.

"Since 1955, we've always had wars around here," said Ouma. "From the time I was 10 until now, we've always been at war."

Reflect on your own or with a partner on the following questions.

- The Ugandans who have welcomed Sudanese refugees have often experienced displacement and disruptions, such as water shortages and deforestation. How has this affected their attitude toward the Sudanese?

- How is this attitude similar to or different from the attitude that people you know have about refugees who want to come to the U.S.?

In the Old Testament, God frequently challenges his chosen people to remember that they have something important in common with aliens — people who come from foreign lands to live among them. From Deuteronomy 10:17-19:

For the Lord, your God, is the God of gods, the Lord of lords, the great God, mighty and awesome, who has no favorites, accepts no bribes, who executes justice for the orphan and the widow, and loves the resident alien, giving them food and clothing. So you too should love the resident alien, for that is what you were in the land of Egypt.

- After being enslaved in Egypt and escaping the wrath of Pharaoh, God's people were familiar with oppression, fear and hardship. What hardships have your ancestors endured — in their homelands or in this country — so that you might live freely?

- Why is empathy — the ability to understand the feelings of others — so important to serving people in times of great need or distress?

Pope Francis recently shared a special message with the young people of the world. In this Christus Vivit, post-synodal apostolic exhortation to young people and the entire people of God, March 25, 2019, he encouraged people to keep open minds about people forced to migrate due to drastic situations:

Grave concern was also expressed by Churches whose members feel forced to escape war and persecution and by others who see in these forced migrations a threat to their survival. The very fact that the Church can embrace all these varied perspectives allows her to play a prophetic role in society with regard to the issue of migration. In a special way, I urge young people not to play into the hands of those who would set them against other young people, newly arrived in their countries, and who would encourage them to view the latter as a threat, and not possessed of the same inalienable dignity as every other human being.

- Many refugees cross borders with few possessions or empty-handed, often with nothing but the clothes on their backs. How do they threaten the nations they enter?

- Why do you think the pope has hope that young people might not get caught up in hostility toward immigrants?

Consider the special perspectives that the sisters in this article have about the people that they serve.

- What qualities does Sr. Helen Tabea see in the Ugandan people that give her hope for the South Sudanese refugees? What must be done to maintain good relations?

- What concerns Sr. Laura Kaneyo about her refugee students? What gifts do she and her teachers use to respond to their needs?

Discuss how a teacher, sister, priest or other leader you've observed used empathy or understanding to ease a stressful conflict.

- Explore how children are exploited and endangered in situations of war and violence around the world. Consider factors that make children more vulnerable and ways to support organizations that protect and heal children threatened or scarred by war.

- Thousands of children are among migrants seeking protection and opportunity in the United States. Consider this list of suggestions from a leading Catholic immigration advocacy group and choose one way to stand up for vulnerable children.

Lord, be with us when we feel lost or hurt.

Send us loving people to guide and heal us.

And when we find peace and the strength to move forward, give us also the compassion to help others who are hurting as we once were.

Amen.

This article comes from the series "Seeking Refuge," published by the Global Sisters Report. You can download the entire e-book HERE.

Tell us what you think about this resource, or give us ideas for other resources you'd like to see, by contacting us at education@globalsistersreport.org