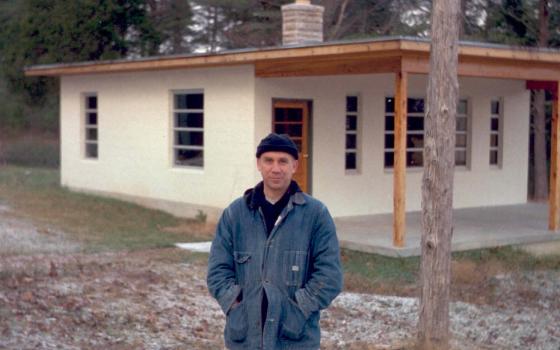

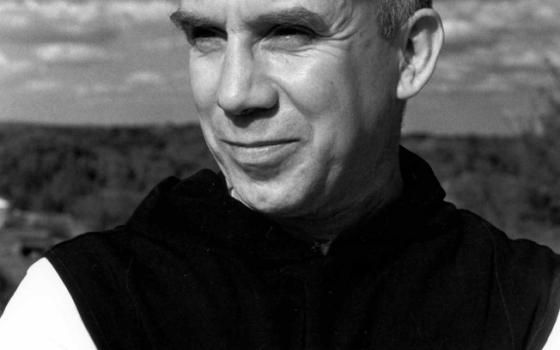

The idea of a long-dead monk having a 100th birthday party is intriguing but not fully surprising when the monk in question is Thomas Merton (1915-1968), arguably America’s most famous monk. There are many such “parties” going on this year, in forms such as retreats, theological symposia, publications, films, academic conferences, liturgical celebrations, art exhibits and public talks. An Internet search reveals events happening on every continent except Africa.

I participated in the four-day conference, Living the Legacy, in Louisville Kentucky, in June, under the organizational expertise of the International Thomas Merton Society. Over 500 people from over 20 countries gathered for the centenary conference. I’m fairly sure there were over 500 motivations that drew these participants together. And perhaps, like myself, as we now read through notes and remember insights we wonder what it was about.

Over the years, I have found challenges and consolations from the writings of Merton. They helped sustain my spiritual imagination and growth during my early years in a religious congregation during the late 1960s and early 1970s. In later years, even though I have continued to turn to my “favorites” of Merton and have perused some newer writings and interpretations, more often, as a spiritual guide, Merton has faded into a past, a world of peace rallies and civil rights dreams long distant.

Why celebrate this birthday party now? I am happy to say, the days were not about erecting some historical monument or updating an icon. And even though there was a moment when the group sang “Happy Birthday,” it was not about sentimental remembrance. A significant aspect was realizing that the monk who died in 1968 is actually alive today, much like an ancestor, often a grandmother, who stays within us as inspiration and much like youthful dreams which, perhaps jaded or trampled, still glow. I experienced new life that urged my spirit in resolve towards living a more human life that sustains and honors the personhood of each through experiences of interior prayer, communities of relationships, analysis of current social situations and active commitment to initiatives toward change and/or resistance.

As I met other conference attendees, chatting informally about their own lives of often simple but creative works, the questions always turned not so much to Merton but to ourselves. Today, as terrorism defines our fears, as the economic field defines so much of our motivations, as brutal human slaughter saturates multiple countries, I found myself challenged anew by a monk of paradox who made contemplation a transparent invitation to analysis and daring. Personally, it poses the questions: Have I forgotten my own birth and lost the revelation of God in the moments of right now in this world, not the world I would like to imagine? Have I settled too long and comfortably in a dulled spiritual system? Questions are what I carried from the conference.

Rev. Bryan Massingale was one example of the superb speakers who helped call me to myself, that is, wake me up to the God I have often left sleeping. Massingale explained Merton’s outspoken analysis of the racial issues of his day which was a contrast to a complacent church that told us (and still does) to just be nicer to those of other races. Merton spoke of moral blindness and systemic challenge; his call for profound change in heart, attitude and social structure seems to me the core of his legacy. Within his presentation, Massingale silently displayed images of the many African American men killed in recent months by police. The group of attendees, as one body, seemed to hold its breath and plunge into contemplative silence that might disclose the social implications of seeing, just seeing, faces while pondering the violent tragedy that besets our nation. Now as our nation has fresh racial hate killings in Charleston and as we pay attention to so many spiritual responses from the targeted congregation, this possibility of deep contemplation and keen social scrutiny is a decisive choice before us.

Such is my own desire: to do deeper analysis, to resist knee-jerk mainstream cultural responses, to contemplate spiritual responses that may have a chance to awaken a birth in our culture and, however slight or small, affect new ways of looking within my own circle of relationships. This was my tiny birth at the conference birthday party. It was quickened by many vibrant themes presented – interfaith hopes, the meaning of God’s presence, re-thinking personhood, and probing what it is to be a church of mercy. Even as news media now clamor to hit upon a good story line on Pope Francis’ new encyclical Laudato Si’, I see the possibility of birth and life again. It is an opportunity to test a stance of deeper response and contemplation, avoiding petty polarizations of left-right, spiritual-political, scientific-religious. Can we turn the analysis to truth, life, and spirit? Can we read the document with eyes of inclusion and love? I am hopeful to maintain this awakened outlook in the face of a world seeming to bleed and disintegrate endlessly as it cries for release from the force of some kind of captivity.

In the end, as I think about the conference, I am left with several out-of-order lines of the untitled poem* that was read during the opening of the conference:

. . . Each one who is born

Comes into the world as a question

For which old answers

Are not sufficient.

. . . This is the theology of our birthdays.

. . . Birth is question and revelation

. . . All theology is a kind of birthday

. . . The ground of birth is paradise

. . . And we wander further away. . .

The words circle around my heart and head and lead me, with God’s help, closer to the juncture of genuine contemplation and faithful social justice. This is a birthday worth remembering.

*Published - In the Dark Before Dawn: New Selected Poems of Thomas Merton, by Thomas Merton, Ed. Lynn R. Szabo

[Sr. Clare Nolan is the International Justice Training Coordinator for the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, an international woman’s religious congregation that is involved in providing social services in about 70 counties, with a particular focus on women and girls in vulnerable situations.]