Recently my attention has been drawn away (thankfully) from national political campaigns and (mercifully) from ISIS atrocities. Unexpectedly, while visiting Kenya, I was pulled toward an awareness of housing.

I've never worked in housing ministry and I often take housing for granted, even as I always feel grateful to return to my own home after time away. My joy is not only in retuning to home "where my heart is" but also in returning to a secure, warm, shelter with running water, ventilation, and much else that goes with middle-class housing in a country such as the United States.

Recent exposure to housing varieties across Kenya opened to me a glimpse into hierarchies of housing that seem to be yet another indication of the looming and growing disparities we have created between human beings. It leaves a sinking feeling with the obvious question, "what to do?"

The most degraded housing I saw was in Western Kenya, in the Kipsongo "slum" near Kitale. Internally displaced tribal peoples with pastoral traditions have migrated in past decades, as prolonged drought in the north and west has killed animal herds and caused famine. The displaced people have settled (squatted) on land that serves as a garbage dump for the town of Kitale. Arriving people constructed shelter out of paper and plastic found in piles of waste underfoot. The beehive shaped structures are about 10 feet in diameter at the base, with entrance openings 3 or 4 feet high and no other ventilation, save the leaks and cracks through plastic layers.

The Sisters of Good Shepherd came in 2008, upon invitation of the bishop, to provide various social supports. The "slum" is now called the Kispongo "community," removing a pejorative label on a place people call home. Still, people continue to live in substandard homes, with government taking virtually no responsibility for relocation assistance, employment support, or permanent stability. Communities remain socially isolated, scorned and feared by long-established residents; they remain largely without skills or hope.

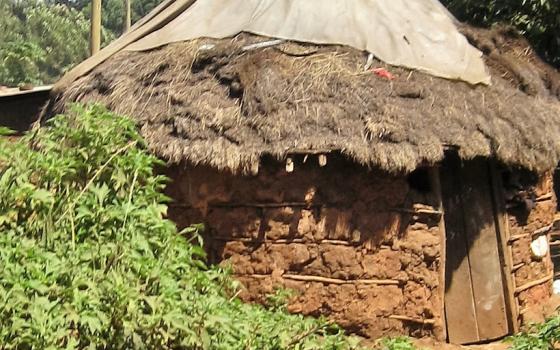

Some settlements have improved. The sisters took me to a community where there has been some upgrading, where most paper and plastic shelters have been replaced with rectangular walls of mud and animal dung, fortified with sticks. They have rusted pieces of tin for roofs, held down by large rocks. At least there was a roof; the rainy season arrives forcefully here. At least there were window openings; heat is oppressive. But the windows have no closure against the rain — back to scrap plastics!

The pride these families took in their upgraded housing was dismal comfort to me as I imagined the dangers of nightfall and cold ground. But I found some solace in the circular shape and thatch roofs of a few of the mud-stick houses, evocative of traditional homes for which, undoubtedly, hearts still yearn. I felt a resilient spirit at work in a people with endurance and some kind of desire for their children and community. In fact, in this improved community children have access to day care operated by the sisters; some have entered and passed primary classes, defying and surpassing the norm of tradition by which older herd-keeping generations have no experience with, or value for, formal schooling. While real, such improvements are slow since the various settlements encompass thousands of persons, and the sisters are only two.

I left Kitale, a long car ride back to Nairobi. I noticed, as I had not on the trip going to Kitale, levels of housing that typify a range of social differences. Going there, it all seemed like stark poverty to me. However, after being in Kitale, I was able to perceive divergent housing wealth on the return trip.

Close to towns and makeshift street markets, the houses were small structures of makeshift bricks loosely piled but able to withstand weather, with scrap tin roofs nailed down. As we approached small cities with more visible schools and shops, the homes were of substantial well-laid brick, with stable roofs of metal alloy sheets, intended for permanence. Finally, as we came into the wealthier suburbs of Nairobi (where many religious institutions have their headquarters and novitiates) we saw large two-story homes, brightly painted, some concrete construction as well as brick, with shiny roofs of painted metal or clay tiles. These homes were difficult to see as they had high walls around them topped by barbed wire, with security guards at gated entrances.

I think this panoramic parade of housing across Kenya could be replicated across the globe. It is a parade of shame where children sleep on dirt floors, and progress consists of mud and sticks while people continue without sanitation, safety, or protection from vermin.

Catholic social teaching has always taught that housing — decent, safe, and affordable — is a human right. Bishops' conferences and Catholic Charities have consistently advocated for governments to form public policy that implements secure housing for all.

I can imagine Pope Francis speaking directly to the residents of Kipsongo rather than to the United Nations when he spoke of a "relentless process of exclusion." How might the community, living on top of a garbage dump, hear these words from the pope's address in September 2015? "Economic and social exclusion is . . . a grave offense against human rights. . . . The poorest are those who suffer most . . . . they are cast off by society, forced to live off what is discarded and suffer unjustly from the abuse of the environment. They are part of today's widespread and quietly growing 'culture of waste'."

In the civil society arena there has been a global movement in the past decade to ensure universal "Social Protection Floors," housing being among the essential basics upon which any human dignity can be built. This is now reinforced in U.N. Sustainable Development Goal #11, the first target of which is to "ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums." This target never stands alone. It is girded about by 16 goals that include food security, resilient infrastructure, sustainable production and consumption, and natural resource conservation, to name a few. Just as each goal cannot stand alone, neither can communities of humanity stand alone; we are in this together and I cannot be complacent in my own comfort when brothers and sisters are suffering so.

Decrees of church and society seem to say the right things, but a connection to the reality of people is too often lost.

The challenge is to understand that the web of human indignities including poverty, unsanitary or no water, meager access to health care, lack of employment, substandard or no education, and disregard for tribal traditions are thoroughly interconnected. A holistic vision is required.

Personally I am called to make the link between lack of housing and the trafficking of women, between inadequate shelter and woeful education, between mental vulnerability and environmental wreckage, between women's empowerment and no place to bathe. But just to define this is not to answer anything.

My hope is that shared awareness can strengthen efforts, can impel fluid movement across areas of expertise, can support partnerships and hold complex interrelationships at the center of all work towards sustainability and human dignity.

[Sr. Clare Nolan is the International Justice Training Coordinator for the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, an international woman’s religious congregation that is involved in providing social services in about 70 counties, with a particular focus on women and girls in vulnerable situations.]