Background note: Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, is a complex country that has for decades been isolated from the international community and from the phenomenon of what we know as globalization. The status of Catholic religious congregations, largely advanced by missionaries during colonial times, is precarious. Christians are a minority status of about 2 percent of the population and in the 1960s all ex-patriots (the largely European elders in religious congregations) were put out of the country in a nationalistic movement that took possession of church properties. The young Myanmar sisters also left for international training; they returned in the 1970s to open ministries, though the large schools they had operated were lost to them.

Today there is a challenge for religious to evaluate ministries in light of a new openness in the country. With much uncertainty, it offers hope for a non-military state and a society can enjoy greater freedoms.

I traveled to Myanmar in June, 2014, in order to present a human rights workshop requested by my congregation, the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, as part of a desire to learn new skills and develop new visions for their ministries. My initial ignorance of this part of the world led to many questions: “What is the difference between Myanmar and Burma?” “Is it Rangoon or Yangon?” “Will the sisters be free to speak about human rights?” My lack of knowledge was diminished by pre-reading of history and politics; other reservations kept my anxiety high until I met the sisters.

The sisters in Myanmar had anxieties as well. Despite good skills with the English language and good education, they lacked confidence about their knowledge of their own national situation because their exposure to the international stage has been limited. There is a lack of general knowledge on Catholic social teaching as a source for ministry development. Their ministries reach out to the very vulnerable in service projects, urban and rural, that include catechesis, health clinics, pre-school nurseries, services for single mothers and village development. Such projects, necessarily accommodating political constraints, are operated with the daily intensity that is required to support the needs of those who live in conditions of poverty but without a larger vision of social transformation or linkages with broader groups of local service providers or international movements.

As I met the sisters, their warmth produced immediate comfortableness for me, and I was most impressed by their enthusiasm to learn. They were open about their lack of exposure to human rights and Catholic social teaching, topics that many of us take for granted. One sister commented, “It is difficult for us to know our own situation because our knowledge is so poor.”

They expressed a determination that new starting points will be essential to develop ministries that lead to not only individual healing but greater empowerment for the vulnerable and far-reaching transformation of their national reality. They were intensely curious about understanding their society and global realities even as they were in a hurry to apply knowledge and theory within their daily activities. As one sister expressed, “We want to see the real needs of our time, to see if we can really take action.”

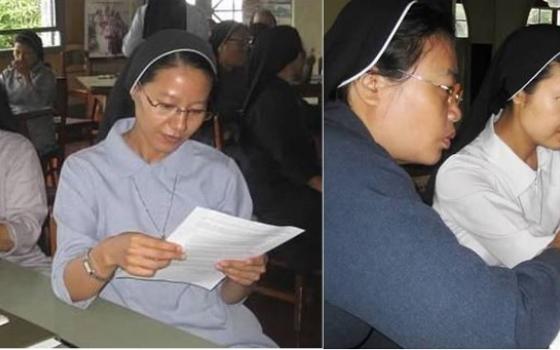

Topics they engaged with were global migration patterns, international trafficking and universal children’s rights. Another sister, realizing a call beyond the day-to-day service work, acknowledged that it will be “difficult to apply project planning; we find it hard but with all our strength I hope we can do it.” The 40 sisters worked for six days in large and small groups, with theory and with practicum exercises, with information and with discussions.

As I write now from New York, 40 sisters in six days of workshop training sounds very mundane. Is this really something to write about? I think it is. It is a listening to the signs of the times; it is an encounter with global forces; it is courage to take up new understanding; it is a commitment to profound change; it is a hope beyond the force of history; it is a belief in spirituality and the dignity of the human spirit. Even though some writing of the details requires restraint, it is still something to write about. Maybe something to sing about!

Justice has not been a word associated with Myanmar in past decades, and many challenges stand in front of this country that has been isolated, fraught with poverty and social neglect. I left, however, with a cautions hope that this will not continue to be the case. One of the workshop participants described as “very difficult” the project of “how to make planning for the future.”

Another sister acknowledged that “it is a long process, it has many risks.” Yet another noted that when they can succeed at putting human rights “into practice in our community as well as when dealing with women and girls who come from exploited and broken situations, I know it can help our effectiveness.”

And the greatest hope, like a pebble in a pond, was expressed by a sister who says, “I came to know about human rights and I will share with others what I have learned.”

Women religious in Myanmar are coming into a new world and a new mission grounded in human rights and Catholic social teaching. It is a sound basis for social, economic and spiritual growth, no matter one’s religion, no matter one’s ethnicity. This is the slow work of God in a region where human settlement with varied and rich tribal identities and cultures dates back 13,000 years.

[Sr. Clare Nolan is the International Justice Training Coordinator for the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, an international woman’s religious congregation that is involved n providing social services in about 70 counties, with a particular focus on women and girls in vulnerable situations.]