Fifty years ago in USA, voting rights became an iconic issue representing social exclusion. While Negros (the racial designation used in the 1950s and into ‘60s) had the right to vote by law, local ordinances and procedures in many states rendered them disqualified and excluded – the core of injustice.

The film “Selma” has drawn national attention to the turbulent times of civil rights activism, political strategies, ideal hopes and still-shocking violence. It clearly shows how those who hold power can consciously and actively exclude those they deem unfit or unworthy of social participation. It can be painful to revisit such times and realize anew what we are capable of doing to one another; it can be heartening to revisit such times and realize that, indeed, progress is possible; and it can be frustrating to revisit such times and look around to places and populations still excluded, still waiting for that far journey that will fulfill justice.

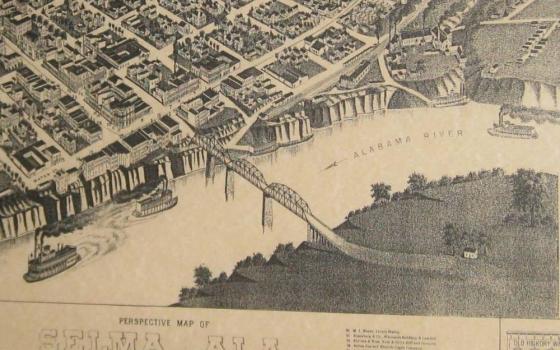

I happened to be in Alabama when the movie was released and decided to take the opportunity to visit Selma-the-city and personally contemplate the Edmund Pettus Bridge (Pettus, 1821-1902, was in turn a Confederate General, a Klu Klux Klan Grand Dragon, and a U.S. Senator.) I wanted to immerse myself in this history and see how it spoke to me, a Northern teenager at the time of the Selma-to-Montgomery march. I found the pilgrimage interesting and soul searching. But the crucial part of my experience, after touring the places and faces of violence and aspiration in Selma was the email I received, late in the day, from a Good Shepherd Sister in an African project where I do consultation.

The email chronicled a recent incident in which violence was inflicted upon a staff member who leads advocacy efforts, including training the community in human rights (for safety I will not identify the project or location). The staff member was accosted, “rounded up by three men unknown to him” in the dark of night when he was walking from his cousin’s house to his own home. As he was beaten, he was given the message to stop supporting consciousness of human rights in the local community – immediately familiar to me after seeing images of the violence delivered to persons in Selma who simply sought their legal right to vote. He was told to deliver the message to all program staff, telling them that it “is dangerous that the community has begun to think they can address politicians.” He was further instructed to “forget any development and rights agenda . . . and stop any media sharing since it displeases the politicians.” The staff member was punched but escaped when a “good Samaritan” happened by and came to his aid.

No burning crosses and no white hooded gowns – simply intimidation and violence with a clear directive to the exploited and vulnerable that they had better stay in their place. That day, reading that email, Selma became a global location for me. It spoke not of the past but of the reality of today. It spoke not of hardship remembered and lessons learned but of justice denied and a movement continuing. It spoke not of a particular location but of a common effort and a universal desire of the human heart. It also spoke, as was well documented in the movie, not only of idealism but of hard-headed strategy required to move justice forward.

In reviewing the historic pictures in Selma, while it is troubling to see the extent of violence perpetrated on the helpless, it was heartening to see women religious in the lines of the marchers – obvious in their distinctive and traditional habits. (Unfortunately, religious dress was carelessly depicted in the movie version.) Globally today we see appalling pictures emanating from every region. As in Selma, we know well, even without distinctive garb, that women religious are in the midst of the struggle today – American Dominicans using media to inform of their visit to the displaced of Erbil, Iraq; Philippine sisters holding placards about systemic roots of poverty and exclusion when the pope visited; international religious communities strategizing to help shape the United Nations’ global agenda, and on and on. Justice is not only about healing fistula and caring for victims of typhoons; it is re-visioning the systems that create such vulnerability and then rolling up one’s sleeves!

Strategy is always difficult to work out. How much risk? How much daring? How much patience? The consequences of strategy are matters, often, of life and death. The program that sent the email to me is in a process of defining their approach. Whatever decisions are made, the strategy is undergirded, as in Selma, with a strong faith in a God who brings good news to the poor and a strong belief in the unquenchable desire of the human heart for justice. The Sister Director of the program who sent the email to me concluded that, within all the uncertainty such threatening provocation brings, the staff has seen “one clear thing, and that we are happy with: the community will never be the same again. Some seed has been sown. Some message has been communicated.”

Selma exists today globally, and women religious are among the multitudes of people of good will moving toward freedom. At this 50-year memorial, we carry the promise of the past to the tasks of today. May none of us be the same again!

[Sr. Clare Nolan is the International Justice Training Coordinator for the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, an international woman’s religious congregation that is involved in providing social services in about 70 counties, with a particular focus on women and girls in vulnerable situations.]