The 1975 pastoral letter by the Catholic bishops of Appalachia, "This Land Is Home to Me: A Pastoral Letter on the Poverty and Powerlessness in Appalachia," inspired many men and women religious, including Sr. Gretchen Shaffer, to go to rural Appalachia to serve the poor and powerless.

What Shaffer, a member of the Congregation of St. Joseph, found when she arrived in Mingo County, West Virginia, on the Kentucky border in 1976 was a land where for at least a century, the powerful had — through both negligence and effort — kept the people powerless. Shaffer knew personally just how the dynamic worked, as her father had been a coal miner.

That same year, Shaffer and Notre Dame de Namur Sr. Kathleen O'Hagan founded a school just outside Kermit, West Virginia, because school consolidations had left the community without one. There was a school bus to take children to another town for school, but there was a law that said if you had to walk more than 2 miles to the bus, you didn't have to go to school at all, Shaffer said. So the children who lived along the ridges towering over Marrowbone Creek didn't go. At least until Shaffer and O'Hagan arrived.

In 1988, Shaffer and O'Hagan's school became Big Laurel Learning Center, and Kermit opened a public school. Shaffer is retired now, but she and O'Hagan are a constant presence in the area, continuing to minister to the powerless.

GSR: Appalachian West Virginia has a long history of this struggle between the powerless and the powerful who wanted to keep them that way. And coal is the biggest example of that. How far back does it go?

Shaffer: In the early 1910s to 1920s, there was a lot of labor organizing going on in mines. See, what the coal companies would do, they would come in and buy people's coal, and people would often sell it not having any idea what the value of it was. So the coal company would get rich and the land owner would get almost nothing. West Virginia is one of those states that you can own the mineral [rights] separate from the surface.

So they would buy up this coal, and then to get workers, they of course would get Appalachian whites. But Appalachian whites were difficult to keep control of because if it was deer season, they'd quit working. They still do that to this very day. Often, the schools will close when deer-hunting season starts. If they wanted to go fishing, they went fishing.

Well, [the coal companies] didn't like that, so they would go up to New York and meet immigrants coming in off the boats. In this area, it was largely Italian, but in other parts of West Virginia, you had Hungarians, Poles, Czechs, Irish, Italian, all in the same community. In Monongah, West Virginia, there were so many different ethnic groups that the Catholic church had four different churches in one small community. So they would get these people right from the boat in New York and bring them in, and they'd get blacks from the South, usually single men.

So once again, someone is getting rich from West Virginia's resources, but the people who live there see little benefit?

That's right. And one of the strategies, one of the ways to keep control of the workers was to pit them against each other. So you'd put the blacks against the whites, the whites against the foreigners, and so on.

That was the beginning of unionizing — getting men to get over those differences that were being encouraged.

But when these men — say they were Italian men. When they came in from Italy, they had nothing, so the company would put them in company houses, which was another way to control what people did, because if you came up against the company for some reason, you were homeless. Not just jobless, but homeless.

They wouldn't give you the tools you needed to dig the coal, the picks and the shovels. They would give them to you 'on time,' so that would be taken out of your pay. Then there was the company store. Well, you could go and charge at the company store, then they took that out of your pay. You couldn't get loose from that, you couldn't pick up stakes and move to where you might have a better opportunity because you owed. So they were indentured servants, basically, and that's what the unions were trying to overcome.

And those were bitter fights, where people died, right?

Oh, yes. And yet last year, our regressive legislature in West Virginia passed a right-to-work law [which removes the requirement for workers to join the union in a union workplace]. I am sure there were more than a few people who turned over in their graves. This was a great blow, especially down here in the southern part of the state. We call it the "right-to-work-for-less law."

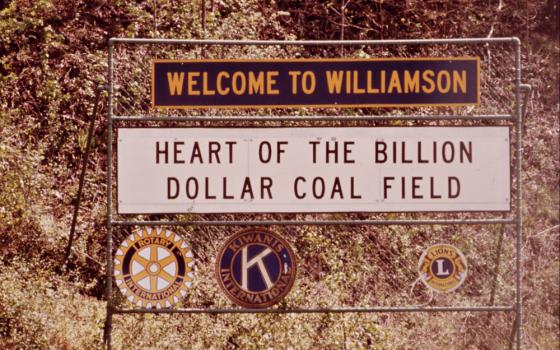

Ever since the early part of the 20th century, coal mining has been the industry. When Kath and I came here in 1976, there was a big sign that said, "Williamson, the heart of the billion dollar coal fields." Ha!

We looked at each other. The roads were terrible, the schools were terrible, there was no kind of recreation for youth or adolescents or young adults, none. If you wanted to go out and have a good time, you had to go to a bar. That was such a contradiction, and it highlighted why the pastoral letter was written in the first place. The question is, why is there so much powerlessness when West Virginia has such mineral riches?

Besides the long history of the power dynamic, was it a big cultural change to move to Appalachia?

We quickly found out they didn't just tell you stuff. And if you were too dumb to ask ...

So we were learning all the time. There was one patriarch in the community that was not at all happy with Catholic sisters coming to the area. There was a lot of prejudice against Catholics. Well, we weren't privy to any of that, and I think it was because certain people in the community who had status that stood up for us. These were longtime residents, and if they thought we were OK, then we must be OK.

[Dan Stockman is national correspondent for Global Sisters Report. His email address is dstockman@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook.]