In 1967 historian Lynn White, Jr., wrote a provocative essay entitled “The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis” in which he blamed Christianity for the environmental crisis. Christianity, he said, with its emphasis on human salvation and dominion over nature, “made it possible to exploit nature in a mood of indifference to the feelings of natural objects.” Because the “roots of our trouble are largely religious,” he claimed, “the remedy must also be essentially religious. We must rethink and re-feel our nature and our destiny.”

Now, almost 50 years later Pope Francis has issued an encyclical that picks up where White left off. His magnum opus Laudato Si’, on Care for Our Common Home, is a work of breadth and depth. Pope Francis has paid close attention to scientific data which indicates that Earth is in crisis: Global warming, water scarcity, loss of biodiversity and other declining factors show that we cannot sustain a first-world lifestyle indefinitely into the future.

Although we have known about an impending crisis for quite some time, we have done little to change our course of direction. In 1990, a group of distinguished scientists, including the late Carl Sagan and physicist Freeman Dyson, wrote a letter appealing to the world’s spiritual leaders to join the scientific community in protecting and conserving an endangered global ecosystem. They wrote, “We are close to committing what in religious language is sometimes called ‘crimes against creation.’”

A world in crisis

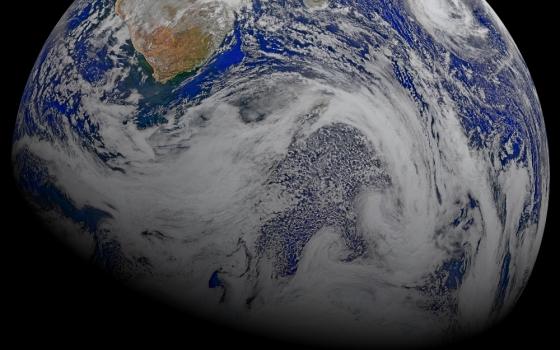

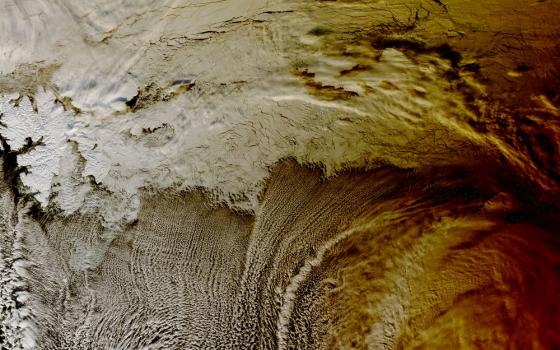

A crisis is defined as a rapidly deteriorating situation that, if left unattended, will lead to disaster in the near future. Pope Francis has raised the planet’s health to a level of crisis. As a planet, we are in danger because the earth’s systems are failing. Many scientists agree that global warming is real, it is already happening and that it is the result of our activities and not a natural occurrence.

We are already seeing changes such as glaciers melting, plants and animals being forced from their habitat, and severe storms and droughts increasing. Scientists predict that deaths from global warming will double in just 25 years, heat waves will become more intense and global sea levels could rise by more than 20 feet with the loss of shelf ice in Greenland and Antarctica, devastating coastal areas worldwide. We are already experiencing some of these changes, and the bulk of destruction is primarily affecting the poor.

Grounded in love

The encyclical of Pope Francis stands apart from his predecessors not only in its breadth of inclusiveness, but in its ecumenical and global appeal and its engagement with modern science. The many excellent conferences on science and religion sponsored by the Vatican have clearly influenced and informed the pope, not only on ecology but also on quantum physics, complexity and evolution. There are signs of these sciences throughout the encyclical, and the pope’s emphasis on interconnectedness indicates the need to move beyond the Newtonian mechanistic paradigm.

He highlights relationality as the new ontos of all life, impelling him to posit a new metaphysics of relationship grounded in divine love. We are not simply human beings for Pope Francis; we are human interbeings and share in the interrelatedness of all cosmic life. He writes: “Everything is related, and we human beings are united as brothers and sisters on a wonderful pilgrimage, woven together by the love God has for each of his creatures and which also unites us in fond affection with brother sun, sister moon, brother river and mother earth” (92).

The Franciscan spirit

Franciscan theology permeates the encyclical, and the pope raises up the patron saint of ecology, St. Francis of Assisi, to new heights. Even Bonaventure is given ample recognition in this encyclical with his doctrine of exemplary creation, the deep relationship between Trinity and Incarnation, and the resurrection as the transfiguration of all creaturely life. I was delighted to read the description of creation ex amore (out of love), as Pope Francis writes, “God’s love is the fundamental moving force in all created things” (77). This is a shift from classical theology which posits the reason for creation either by divine freedom (Thomas Aquinas) or divine will (Bonaventure).

Laudato Si’ shows a deep, Franciscan understanding of creation flowing forth from the heart of God in which every creature expresses God in some way. The world is created as a means of God’s self-revelation so that, like a mirror or footprint, it might lead us to love and praise the Creator. Francis of Assisi’s beautiful Canticle of Creatures frames this encyclical with a passion for wholeness and unity in the overflowing love of God. Franciscans all over must be rejoicing that, finally, Bonaventure and John Duns Scotus are getting their due recognition.

An inherent roadblock

While the encyclical of Pope Francis has my enthusiastic support, with its intelligence, ambitious outreach and bold engagement with science, the encyclical bears an inherent irony that rests on the relationship between cosmology and anthropology. There is a subtle intransigency in the text to change our core doctrine of the human person, and, in my view, this roadblock precludes the pope’s agenda for a global shift in consciousness.

To understand this dilemma is to begin with Francis of Assisi. Laudato Si’ opens up with the words of the Canticle of Creatures, composed by Francis of Assisi a year before his death. It is a hymn that is doxological in structure, the glory of God resounding throughout the universe in and through the risen Christ whose life now flows throughout the cosmos through the life-giving Spirit. The nature mysticism of Francis of Assisi and the theological vision it inspired must be understood, however, within the framework of the medieval cosmos, a fixed, stable structure of orderly life with the Earth as center.

As earth was center of the cosmos, the human person was center of the earth. The human person, created in the image of God, was the “noble center,” as Bonaventure taught. The medieval person had a consciousness of belonging to a whole; cosmos and anthropos were deeply entwined. This kind of thinking led to a deep, integral relationship between the human person (microcosm) and the cosmos (macrocosm). In other words, the human had a role in creation, to reconcile matter and spirit in union with Jesus Christ.

The rise of modern science

This consciousness of belonging to the cosmos changed with the discovery of heliocentrism and the rise of modern science. When Nicholas of Cusa and later Nicholas Copernicus proposed a sun-centered universe (heliocentrism) the church was not ready for the major upheaval of a moving Earth. If the Earth moved around the sun, then the human person was no longer center of a stable Earth but simply part of a spinning planet. How could this finding be reconciled with the Genesis account where the human person was created on the sixth day, after which God rested? How would sin and salvation be understood? From the Patristic to the Middle Ages, theology and cosmology were united. Theology, like philosophy, was not a particular science; rather it was related to the whole. Cosmology was part of theology as long as the cosmos was believed to be God’s creation. The rise of heliocentrism changed this God-world relationship.

The separation of science and religion

The crises that Pope Francis highlights in Laudato Si’ are not due to recent events; rather they are at least 500 years in the making and are the consequence of cosmological and metaphysical shifts in our understanding of self and universe. Religiously, we have maintained a synthesis that is medieval in structure, while modern science has disclosed a world of change. To this day our prayers and worship reflect a fixed, three-tiered universe even though we do not live in such a universe.

We have become radically disconnected from one another because we have become radically disconnected from the whole, the cosmos. Nancy Ellen Abrams and Joel Primack expound the relationship between cosmos and anthropos in their book, The New Universe and the Human Future: How a Shared Cosmology Could Transform the World, indicating that a shared cosmology can help transform our fragmented world into a new unity: “There is a profound connection between our lack of a shared cosmology and our increasing global problems. We have no sense how we and our fellow humans fit into the big picture. . . . [W]ithout a big picture we are very small people.” Similarly, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin noted in the mid-20th century a split between the human person and the cosmos and claimed: “The artificial separation between humans and cosmos is at the root of contemporary moral confusion.”

This division between the cosmos (or universe) and the human person has resulted from the split between science and religion. It is this split that Pope Francis is seeking to address in the encyclical because he realizes that we cannot go forward into a sustainable future without the insights of both science and religion. Thus he addresses the encyclical to all people of good will and states up front that “science and religion, with their distinctive approaches to understanding reality, can enter into an intense dialogue fruitful for both” (62). It is precisely how science and religion relate, however, that is ambivalent in the encyclical.

Old and new creation

On one hand, Laudato Si’ supports evolution without quite explicitly saying so. Rather, the pope writes that God is “creating a world in need of development” (80, emphasis added), and God’s role in this process is one of selfless love. Using the Jewish kabbalist notion of Zimzum (divine withdrawal), the pope states that “God in some way sought to limit himself” in this creating process, thus allowing new things to emerge (80). He sees God’s love as “the fundamental force in all created things” (77, emphasis added) and the power of love “intimately present to each being, without impinging on the autonomy of the creature,” allowing creaturely life to unfold in freedom (80).

Hence, Pope Francis points to a theology of evolution in this encyclical in a way that promises a new vision for the world; however, he reverts to an old theology when he states: “The best way to restore men and women to their rightful place, putting an end to their claim to absolute dominion over the earth, is to speak once more of the figure of a Father who creates and who alone owns the world” (75). When it comes to the human person, the evolutionary paradigm is jettisoned for special creation and divine intervention. The pope writes: “Human beings, even if we postulate a process of evolution, also possess a uniqueness which cannot be fully explained by the evolution of other open systems. . . . Our capacity to reason, to develop arguments, to be inventive . . . are signs of a uniqueness which transcends the spheres of physics and biology. The sheer novelty involved in the emergence of a personal being within a material universe presupposes a direct action of God and a particular call to life” (81, emphasis added). Francis reaffirms the position of Pope Pius XII, who wrote in Humani generis that the human body may come about by way of evolution but the soul is created immediately by God (36). Despite the fact that Pope Francis relies on Teilhard de Chardin, for example, describing the Eucharist as a living center of the universe, “an act of cosmic love” which is celebrated “on the altar of the world” (236), he affirms that “Christian thought sees human beings as possessing a particular dignity above other creatures” (119).

Pope Francis seeks a renewed humanity, but a new humanity cannot be found apart from a renewed cosmology and a renewed theology, as Raimon Panikkar reminded us: the name “God” is a cosmological notion, for there is no cosmos without God and no God without cosmos. In short, if our cosmology has changed, so too our theology and anthropology must change. These three realities – cosmology, theology and anthropology – are so deeply intertwined that one cannot extract particular sections from any one of these areas or “cut and paste” and hope to find comprehensive meaning. They must be held together if they are to be understood together.

The significance of big history

What I find missing from Laudato Si’ is the 13.8 billion year old Big Bang universe story or what is known today as “Big History,” which examines history from the Big Bang to the present using a multidisciplinary approach. This is the story of the modern human person who has emerged slowly, over deep time, through complex levels of biological evolution. However, if we begin to tell the human story as one of emergent life within cosmic history, we lose the nobility of the human person as “unique” or special; that is, the human person uniquely created in the image of God. And here we begin to encroach on Christology, because the nobility of the human whose image was deformed by the sin of Adam and Eve was restored to divine likeness in Jesus Christ. In other words, once we accept cosmic history (or Big History) as our story, then the whole theological edifice of the Catechism of the Catholic Church begins to falter. Every aspect of theology, including sin and salvation, would have to be rethought in light of evolution and in light of an incomplete universe seeking its fulfillment up ahead.

The vision of Teilhard de Chardin

No one understood better the implications of evolution for theology than the Jesuit scientist, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. He indicated that dialogue alone is insufficient to move us to a new level of consciousness and new action in the world. What is needed, he indicated, is a new synthesis that emerges from the insights of science and religion. Evolution, he maintained, is neither theory nor particular fact but a “dimension” to which all thinking in whatever area must conform. The human person emerges out of billions of years of evolution, beginning with cosmogenesis and the billions of years that led to biogenesis. To realize that humans are part of larger process which involves long spans of developmental time brings a massive change to all of our knowledge and beliefs.

In the past, Christianity had been above all a religion of order. The fundamental question Christians asked themselves had always been the same: What is the significance of Christ in a world which was created in a perfect order but has been upset by original sin? The answer was unambiguous: Christ had come to restore the order destroyed by sin and to lead the world back to its original perfection. Now what we must ask is: What is the significance of Christ in an evolving world, at the heart of humankind seeking its future?

By abandoning the doctrine of original sin, Teilhard was able to see the incarnation more coherently in its relation to creation so that the mystery of creation and the mystery of incarnation form a single mystery of divine love. This world is not merely a plurality of unrelated things but a true unity, a cosmos, centered in Christ who is the purpose of this universe and the model of what is intended for this universe, that is, union and transformation in God.

Teilhard used the term Christogenesis to indicate that the biological and cosmological genesis of creation – cosmogenesis – is from the point of faith, Christogenesis. The whole cosmos is incarnational. Christ is organically immersed with all of creation, in the heart of matter, thus unifying the world. Teilhard introduced a new understanding of Christ as the “evolver,” the power of divine love incarnate within, who is one with Christ Omega. He posited a dynamic view of God and the world in the process of becoming something more than what it is because the universe is grounded in the personal center of Christ.

Technology and the noosphere

Teilhard was convinced that the total material universe is in movement toward a greater unified convergence in consciousness, a hyper-personalized organism or “an irreversible personalizing universe.” Jesus Christ is the physical and personal center of an expanding universe and the Spirit sent by Christ continues evolution in and through us. He saw unification of the whole in and through the human person who is the growing tip of the evolutionary process. He spoke of the human person as a “co-creator.” God evolves the universe and brings it to its completion through the human person. Before the human emerged, he said, it was natural selection that set the course of morphogenesis; after humans it is the power of invention that begins to grasp the evolutionary reigns.

Whereas Laudato Si’ speaks somberly of technology and technocratic power (102-114), Teilhard saw the computer ushering in a new level of shared consciousness, which he called the noosphere, a level of cybernetic mind giving rise to a field of global mind through interconnecting pathways. He insisted that technology is a new means of (evolutionary) convergence; humankind is not dissipating but unifying by concentrating upon itself. We call this new level of consciousness “global consciousness” because we now have awareness of life around the globe in a way unprecedented in human history. But Teilhard also saw that this new level of global mind could give rise to a new level of shared being and shared consciousness, a new level of unity reflecting the emergence of Christ. In this way, Teilhard saw that technology could further religion at the heart of evolution.

A religion of the earth

Teilhard felt that traditional Christianity still lives too aloof from the world – too much at odds with “the natural religious current” of contemporary humanity, a closed system of routinized sameness. He wrote: “No longer is it simply a religion of individual and of heaven, but a religion of mankind and of the earth – that is what we are looking for at this moment, as the oxygen without which we cannot breathe.” He called for a new religion of the earth rather than a religion of heaven.

Religion, in Teilhard’s view, is primarily on the level of human consciousness and human action, rather than in institutions or belief systems, except insofar as these manifest and give direction to the former. In his final essay The Christic he wrote: “In a system of cosmo-noogenesis, the comparative value of religious creeds may be measured by their respective power of evolutive activation.”

Teilhard said that “the crises of our time are challenging the world religions to release a new spiritual force transcending religious, cultural and national boundaries into a new consciousness of the oneness of the human community and so putting into effect a spiritual dynamic toward the solutions of world problem. . . . We affirm a new spirituality, divested of insularity and directed toward a planetary consciousness.”

Old and new beliefs

Like Teilhard, Pope Francis believes that human consciousness finds itself on the threshold of a new age which requires entirely new dimensions and values. The deepest beliefs of human beings must find new forms of expression. Unlike Teilhard, however, the pope has not called for a new consciousness and relatedness within the church. Yet as Lynn White, Jr., claimed, “since the roots of our trouble are largely religious, the remedy must also be essentially religious.”

The core principles of the Judeo-Christian tradition, such as the fall of Adam, divine likeness and historical progress (resurrection and pleroma) have contributed to the rise of modern science and hence modern culture. These principles are also deeply embedded in the church’s prayer life, core theological doctrines and religious rituals. Because the law of belief (lex credendi) is the law of life (lex vivendi), there is a deep connection between ancient religious prayers, beliefs and rituals at the heart of our ecological disconnectedness. What we profess in faith, the language used to express those beliefs, and the structure of worship that ritualizes those beliefs, are all wired into our religious DNA. We are programmed for heaven above not an earth in evolution; God up above not God up ahead.

The church in evolution

Teilhard had a vision of the church in evolution. He spoke of the church as a new phylum of Christian amorization in the universe. By speaking of the church as a phylum, he imagined a new christified humanity, bonded by love, that would amorize (from the Latin amor or “love”) the cosmos and kindle love in the evolving cosmos. Anchored in the cosmic Christ, the church bears witness to the living God as the life of the world and hence to its own life as the Body of Christ in evolution. The mission of the church therefore is the christification of the universe and the personalization of divine love at the heart of cosmic life. In other words, the church does not exist for itself, it is exists for the world. Teilhard said that a new vision of the universe calls for a new form of worship and a new method of action.

Conversion and conscious evolution

Laudato Si’ is calling for new action but this cannot be effective without sinking its roots into a new consciousness of church and hence Christian life in evolution. Pope Francis wants the world to change but does not see that change must take place within as well. Unless we change the way we think and pray, we will not change the way we act. Evolution, Teilhard said, is the rise of consciousness; as we begin to see self, God and world in new ways, so too do our actions follow. Only when a new level of religious consciousness emerges will a new reality emerge.

Conversion is essential, as the pope indicates, but it cannot be spiritual conversion alone. Rather, conversion must take place on every level of ecclesial life – spiritual, theological, structural, organizational, interreligious – until the world begins to feel the spiritual impulse of love at the heart of all life.

Laudato Si’ opens the doors to a new world by challenging a selfish world of disconnectedness and calling all people to a new world of interrelatedness. But the Church must model the very principles it promotes: mutual relatedness, inclusivity, interdependence, dignity of all peoples, shared resources and responsibilities, all creatures united together as brothers and sisters, woven together in the love of God. Teilhard de Chardin had a vision for the Church in an unfinished universe and I encourage Pope Francis to look to Teilhard’s evolutionary vision for the 21st century, to make Teilhard de Chardin a Doctor of the Church and to bring the good work he has begun to the next level of evolution.

[Ilia Delio, a member of the Franciscan Sisters of Washington, D.C., will be the Josephine C. Connelly Endowed Chair in Theology at Villanova University starting in August, 2015. She is the author of 16 books and the general editor of the series Catholicity in an Evolving Universe. Her new book Making All Things New: Catholicity, Cosmology and Consciousness will be published by Orbis Books in fall 2015.]