We use the adjective tragic when speaking of young persons who die from accidents, cancer, suicide and violence. After all, don't we expect human beings to live long and full lives?

Here in the United States, our average life expectancy is 78.5 years overall, with men living an average of 76 years and women living an average of 81 years, per the World Health Organization, 2016. Even though this only ranks the U.S. at 45 out of 201 countries for longest life expectancy in the world, living 78.5 years is still considered a full life.

My five siblings and I agonized at Christmastime in the later years of our parents' relatively long lives, struggling to figure out what gifts to get them. In our Catholic family, Baby Jesus was a gift to the world and symbolized our gift-giving to each other. But how many shirts or nightgowns or the like does an older person need? In truth, our parents didn't want things. Our parents didn't want presents to unwrap. Our parents were way beyond material gifts — but we didn't pay attention. We went shopping anyway.

What our parents actually valued most was being together as a family, everyone getting along, welcoming new spouses and new babies, and hearing about what was happening in everyone's lives.

The phenomenon underway escaped me for a long time. Mom and Dad went to heaven years ago, so they're no longer around to ask. But as I'm getting older, I'm starting to think like they did about things. I, too, don't need or want more "stuff." Now I realize that secret and that wisdom coming with age.

Recently, I read this quote from St. John of the Cross about the narrow pathway: "The road is narrow. One who wishes to travel it more easily must cast off all things and use the cross as a cane." He was paraphrasing the Scripture passage from Matthew that exhorts entering through the narrow gate that leads to life: "Go in by the narrow gate. For the wide gate has a broad road which leads to disaster, and there are many people going that way. The narrow gate and the hard road lead out into life, and only a few are finding it."

My mind flooded with images from my last geographic move. I had plenty of belongings to move, including a beautiful grand piano that I played often. But using that St. John reminder, in my mind I pictured myself struggling down a gradually skinnier pathway as I approached the narrow gate with the grand piano on my back. While I could fit down the path — the piano couldn't. So then and there, I decided it was time to share the piano with a sibling who was glad to get it. That same scenario replicated with other possessions that I once needed but didn't any longer. It was liberating.

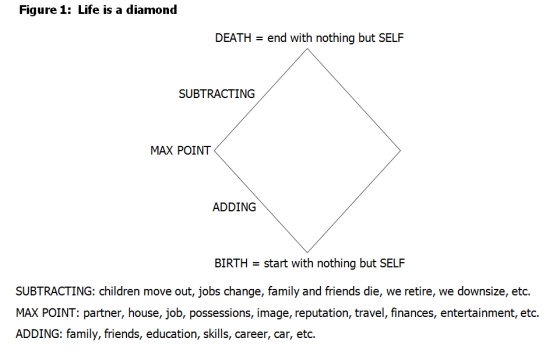

In thinking of how to describe this, picture a diamond — life is a diamond (see Figure 1).

We come into the world with only ourselves. (Picture the bottom point of the diamond.) This is our small entry point into the world — a narrow gate of its own.

We grow up, we learn and we start our own lives, which puts us in an "adding" mode. (Picture the lower sides of the diamond.) We then reach a point where we "max out" in the things that are part of life — partner, children, house, car, job, possessions, image, reputation, travel, finances, entertainment, etc. (Think the widest part of the diamond.) This maximum point occurs when we have everything and everyone we could possibly need — and then some. We may not know that we've reached the maximum point, though, until after we've passed it.

Now what about someone in the world who doesn't have many possessions? Does the diamond analogy apply to him or her as well? Let's think about that. I suggest that a person anywhere — even a homeless person or someone living in a simple hut — gets to a point when the bigger question of life takes over. The individual looks at his cardboard box or her rice bowl or whatever and thinks, "Do I even need this any longer? Why?"

So something changes for each of us. At some unspecified moment, we start subtracting. Children become adults and move away. Jobs change, family and friends die, we retire, we clean out basements and closets, we downsize into a smaller residence, we may have health issues that require simpler living, and even once favorite foods aren't favorite anymore. We don't have the same needs as before. We're not even interested in possessions like we once were.

We start subtracting. (Think the upper sides of the diamond.) This subtracting is gradual and we may not realize the significance, but what we're really doing is preparing our lives for the point opposite of our birth point on the diamond. In this subtracting, we become especially reflective about all sorts of things, including spiritual readiness for the narrow gate.

Eventually, we will arrive at the end and leave this world the way we entered it — with nothing but ourselves. No wealth or clothing or possessions or even grand pianos. Just ourselves. (Think the top point of the diamond.)

The top and bottom points of the diamond are similar since both are narrow. As we move from birth at the bottom toward death at the top, we keep honing and readying ourselves to fit through the narrow path. This honing and readying is not just focused on material things, but it's also a readying of mind, attitude, soul and spirit.

The words of Christ encourage me: "I am the gate. Whoever enters through me will be safe." Life is a diamond — precious, full and meant to be lived well so that I can make it worthily down the pathway toward my personal moment to meet Christ, the gate.

[Nancy Linenkugel has been a member of the Sisters of St. Francis, Sylvania, Ohio, since 1968 and writes blogs for her community's website. She is an alumna of Xavier University's Master of Health Services Administration program and serves as its director. She was president and CEO of Providence Hospital and Providence Health System from 1986 to 2001.]