I still remember the shock I felt when reading an email that was forwarded to me on Jan. 30, 2009. I was the president of my community at the time. The email reported that a press release announcing the apostolic visitation of communities of women religious in the U.S. had just been issued. I didn't really know for certain what an apostolic visitation was or the ramifications of this announcement, but I sensed it was an ominous message.

Thus began the journey through the four phases of the apostolic visitation, which was ordered by the Vatican's Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life (CICLSAL) to examine "the quality of life" of women religious in the U.S. The visitation was completed in early 2012 with the submission of a report to the Vatican by Mother Mary Clare Millea, who had been appointed to conduct it. The content of the report is unknown.

Now, some wonder when, or if, a public response from CICLSAL will be forthcoming. Or what it will say. I suppose at one time, most of us women religious in the U.S. would have been quite anxious about this. Not anymore.

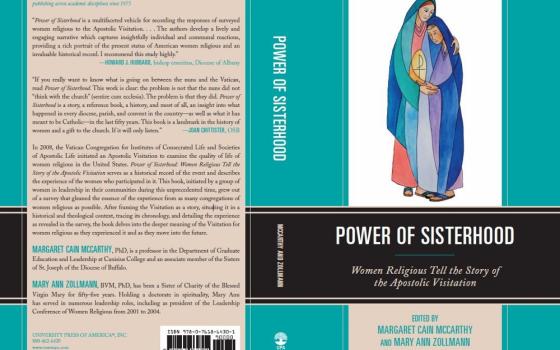

Power of Sisterhood: Women Religious Tell the Story of the Apostolic Visitation, the new book published by University Press of America, affords readers plenty of insight into why that is.

This book was initiated by a group of women religious who were the elected leaders of their communities during the apostolic visitation. They recognized the importance of capturing and telling the story from the perspective of the women who experienced it. So in 2010, with the assistance of Margaret Cain McCarthy, Ph.D., they designed and conducted a qualitative and quantitative survey of presidents or major superiors whose communities had undergone the visitation.

(The book deals only with the apostolic visitation. It does not cover the Doctrinal Assessment of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, which was also announced in 2009.)

If you want to understand the various phases and track the visitation from prior to the time of the press release until the present, check out chapter three by St. Joseph Sr. Jean Wincek and Providence Sr. Nancy Reynolds.

The context

Examining the context for the visitation offers a fuller understanding of it and the women's responses. In the first chapter, Mary Ann Zollmann, a Sister of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, addresses the question of what apostolic visitations are and the history of their development within the church. She distinguishes the types of visitations and explains that for an administrative visitation the accusations are not revealed, the purposes are nebulous, the procedures lack transparency and safeguards are missing. Tracing the influence of Vatican II on ecclesial processes, Zollmann illuminates how the way the visitation was announced and conducted clashed with the collegial experience of the women leaders.

Dominican Sr. Patricia Walter, in chapter two, situates the visitation in the historical and theological context. In doing so, she has identified six major themes or issues that led to the visitation, ranging from the evolving and pluralistic nature of religious life itself, through the inherent tension between the hierarchical structure of the church and the rightful autonomy of religious institutes, and the renewal of structures following Vatican II to feminism.

The survey

Chapters four and five delve into the book's survey itself: its design, the questions, a sampling of responses to each question and McCarthy's analysis of themes that arose. The survey was designed to gauge the level of participation and reactions of the leaders and the sisters in their communities throughout all the phases of the process. The leaders were also asked how they engaged others, where they found support and what were their hopes and fears regarding the outcome. By including a sampling of responses to each question, McCarthy gives the reader a first-hand view from the perspective of the 143 leaders who responded to the survey.

You can read more about the analysis of the survey here.

Delving into the experience

The remaining chapters of the book are written by sisters who reflect both on their own experience and what is revealed through the survey responses. Using metaphors and scriptural passages, they explore what happened in and among women religious communities through the process of the visitation, the deeper meaning of it, some surprising beneficial outcomes and how those might influence the way forward.

St. Joseph Sr. Marcia Allen, in a chapter entitled "Living It Twice," explores the sources of support and inspiration of the leaders. Addie Lorraine Walker, a School Sister of Notre Dame, utilizes theological reflection to probe more deeply into the meaning of the experience. Loretto Srs. Donna Day and Cathy Mueller use metaphor to probe the most important part of the story in a chapter entitled "Balanced on Thin Ice." Zollmann reflects on Luke's Gospel account of Mary's visit to Elizabeth to unfold the experience.

Herein lies the richness of the multi-layered story. The various dimensions and facets offered in these chapters deserve rereading and pondering. This is a story that could provide valuable insights applicable to other situations in the church.

"The Apostolic Visitation is a challenging story about solidarity, integrity and transformation," write Day and Mueller in a succinct summarizing statement.

Solidarity

Solidarity is a recurring theme. Leaders approached the apostolic visitation with the collaborative working styles, communal dialogue and decision-making skills that they had developed since Vatican II.

Because the visitation was not directed to one or two congregations but to all women religious with active apostolates, the leaders had a keen awareness that the response they chose to make had implications for not only their own congregation but for the lives of all women religious in the U.S., globally and for the church as a whole. They involved the sisters of their communities in the process and consulted with one another. Other religious and laity offered their support. Consequently, solidarity among women religious and with laity developed through the process.

Allen writes, ". . . there is a side to this story that bears repeating not just once but many times. It is the story of solidarity. . . ." Day and Mueller call it a gift. Zollmann speaks of it as community, writing, ". . . we claimed the living of community as our identity and its creation as our mission." Zollmann refers to a "great wide global sisterhood," while Allen emphasizes that the networks that developed have created a new reality.

Just as the book does not shy away from honestly naming the negative reactions and emotions of the leaders, the marginalization of women in the church and the tensions with the hierarchical structure of the church, neither does it dodge the reality of the brokenness of sisterhood.

In the early 1970s some major superiors separated from the Leadership Conference of Women Religious. Eventually this led to the formation of the Council of Major Superiors of Women Religious, which received Vatican approval in 1992. Walters names this "now institutionalized and officially recognized" split "a source of pain and probably scandal." Zollmann refers to "this division between two valid expressions of religious life" as a "hole in the community of our sisterhood." Both hope that one of the fruits of the apostolic visitation itself will be the recognition and welcoming of the diversity of expressions of religious life in living the Gospel, bringing about healing.

Integrity

Women religious took seriously the call of Vatican II for renewal.

"It would be difficult to overstate the importance of Vatican II in the lives of American women religious," writes Walter. That reality is evident in the answers to the survey and in each chapter. They had turned to scripture and the spirit of their founders. They made "the joys and the hopes, the griefs and the anxieties of the people of this age" their own (Gaudium et Spes). They adapted to the times. They changed.

"Accordingly, the Apostolic Visitation landed in our lives as a judgment on the women we had become in response to the invitation of our church," writes Zollmann.

They responded to the apostolic visitation out of who they had become. Once again, women religious delved into their constitutions and found "renewed energy for their charism" and "an intensification among us regarding our commitment to live the gospel fully." (Day and Mueller). They grounded themselves in contemplation and nonviolence. They worked collaboratively.

"Because we lived into the renewal mandated by Vatican Council II to return to our roots, to renew ourselves in our charism, we could look at our reality and not compromise the truth of our lives," Day and Mueller write.

In writing about Phase II, the questionnaire, Zollmann states, "As we worked with the language of the document and its assumptions about our life, many of us came face to face with the undeniable gap between our own self-definition and the official church's expectations of us. We had grown beyond the boundaries of those questions; they simply did not fit us; they were too small for the women we had become."

No wonder only 15 percent of the leaders chose to answer all the questions.

The apostolic visitation also brought to the forefront their reality as women in the church. It affected their initial and ongoing reactions, how they responded and how they reflected on the meaning of the experience.

"Despite the great contributions of women to the building of the church in America, women continue to experience being marginalized: no seat at the table, no voice in the shaping of the report or follow-up decisions that impact the oversight of religious life, and no participation in the overall governance of the church," writes Walker in chapter seven, "Theological Reflection on the Apostolic Visitation."

"The ‘genius,' talents, and the collective giftedness of U.S. women religious' leadership, for the most part, is experienced as absent from the overall process of the Apostolic Visitation: the identification of the need for such an investigation, the consultation with congregational leadership about the concerns calling for such a formal visitation of the majority of congregations in the U.S., the announcement to the congregations and the public, the design and implementation of the process."

Walker continues, "The Apostolic Visitation seemed to force women religious to come to grips with their situation of subordination: finding voice, claiming and affirming identity, critiquing the situation in light of their vocational call."

Transformation

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the apostolic visitation was that it became a transformative experience. Women religious came through it with a new-found solidarity, greater strength, a renewed commitment to living the Gospel and a sharper focus on their identity.

Day's and Mueller's description capture the experience:

"We responded in a manner true to our lives. We talked with one another, shared emotions, possible scenarios, and strategies. The value of conversations both within congregations and among congregations helped us to look at the Vatican's request, to remember who we are, and to move to a response that could be constructive. This was a turning point. We encouraged one another to follow our own charism and to rely on the wisdom in our communities. As individual congregations made different responses, the other congregations treated each congregation's response with respect. We could honor the diversity among us; we experienced the solidarity."

Walker spoke of it in these terms:

"This somewhat latent power of community called to the fore creative energy from the heart of the various charisms and evoked courageous fidelity to the very mission of apostolic religious life itself, not just for a particular congregation, but for all congregations together – truly a collective vocational moment for women religious in the U.S."

She even sensed a transformative power within the experience of marginalization:

"However, it was in the midst of this sense of marginality or within a context of subjugation that women religious found a unique sense of liberating power along with the meaning and purpose of their prophetic voice."

A difficult situation became life-giving, Day and Mueller wrote. And even a source of hope according to Walker: "Faith and trust in God who accompanies were clearly the prevailing virtues accessed throughout the process. . . . Seemingly the biggest unintended and unexpected consequence of the collective experience of women religious in the U.S. was enduring hope."

And so, we await CICLSAL's public announcement of their response.

But even in the waiting lie the seeds of transformation:

"In an ironic and paradoxical way, the lack of a Vatican evaluation has given us the opportunity to cull out our own meanings and learnings from the event, liberating us to break through and beyond the confines of Rome's assessment of us," Zollmann writes in the Epilogue "The Power of Silence."

[Jan Cebula, is a Franciscan Sister of Clinton, Iowa, is a liaison for Global Sisters Report to women religious and organizations in the United States.]