Somewhere in the decision made by the teenage Thea Bowman lay a paradox worthy of a biblical epic. A Protestant child of the Deep South and childhood convert to Catholicism, she chose one of the whitest places possible to work out who she was as both a vowed religious and a black woman.

The significance of her decision and the consequence of the meeting of those seemingly incongruent worlds was on display in late March when some 85 followers and devotees from spots as distant as Seattle and Camden, New Jersey, gathered in LaCrosse, Wisconsin, for an observance of the 25th anniversary of Bowman’s “homegoing.” The two-day event included a panel discussion in St. Rose Convent of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, located near the campus of Viterbo University, which the order founded. Bowman taught at the university from 1972 through 1978. The following day, a live-streamed Mass was celebrated in the order’s distinctive Mary of the Angels Chapel.

When the 15-year-old Bertha Bowman (her birth name was Bertha Elizabeth, and her nickname was Birdie) was about to leave Canton, Mississippi, for her new life in La Crosse, her father, Theon Edward Bowman, understood far more than his daughter the challenges she might face. Bowman, a physician, was but a few generations removed from the harshest reality of black life in America. Relatives on his father’s side had been slaves.

Theon and his wife, Mary, a teacher, had already gone toe-to-toe with their very determined daughter. The couple, who had seen their only child convert from the Methodist church to the Roman Catholic church at age nine, were adamant. They forbade her to go off to become a nun. The teen wouldn’t back down, and began a hunger strike. Birdie finally “finagled her parents’ permission to go to LaCrosse,” as recounted in Thea’s Song: the Life of Thea Bowman, a biography by Sr. Charlene Smith and journalist John Feister. Smith, also a member of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, was a contemporary of Bowman’s and an organizer of the March 29-30 event.

Bowman’s father made a last-ditch attempt to discourage the youngster. “They’re not going to like you up there, the only black in the middle of all the whites,” he said. To which she responded, “I’m going to make them like me.” Her parents eventually followed her into the Catholic church.

Certainly many members of her order came to like her and eventually see her as a model. But Bowman also faced difficult days during her formation. According to Thea’s Song, she encountered, especially during her early years, attitudes ranging from curiosity to resistance to downright ugly racist remarks, particularly from older members of the community. Black sisters were rare in any circumstance, and Bowman was unique in the FSPA’s experience.

What is perhaps more significant is that over the course of her time in La Crosse and in the relatively short period of ministry that followed (she died in 1990 at age 52 after dealing with cancer for several years), Bowman made members of her order and countless others take notice. One can imagine that Theon was worried that his daughter would lose her black identity and become more white in order to fit in with the sisters who had educated her as a child and whom she had come to admire. Quite the opposite occurred. In time, she became an icon of black Catholicism enamored of her African roots and confident enough to declare the importance of her heritage to a gathering of the U.S. bishops.

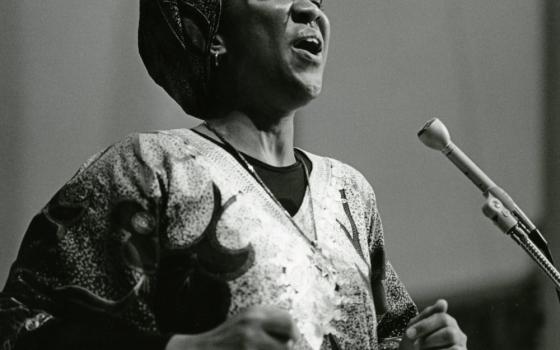

In a memorable scene that might well represent the apex of her ministry, Bowman went before the assembled bishops in June 1989, the rare woman invited and permitted to address the country’s hierarchy. From a wheelchair, racked with cancer that had metastasized to her bones and months before her death, she pronounced:

What does it mean to be black and Catholic? It means that I come to my church fully functioning. That doesn’t frighten you, does it? I come to my church fully functioning. I bring myself, my black self, all that I am, all that I have, all that I hope to become. I bring my whole history, my tradition, my experience, my culture, my African American song and dance and gesture and movement and teaching and preaching and healing and responsibility as gift to the church.

Bowman obviously had not gone white. And though she made the case for black Catholics, indeed emphasizing to the bishops that “the majority of the people in the world are not white Europeans,” it was a thoroughly white order rooted in Germany that had become her second family.

She once said she loved the FSPA teachers “because they first loved us.” The order, which accepted a pastor’s request to start a school in Canton in the late 1940s, was actually young Bertha Bowman’s second encounter with Catholicism. Her first, which led this precocious seeker to her new denomination, was with priests, sisters and brothers of the Missionary Servants of the Most Holy Trinity.

The Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, recognizing her intellectual gifts, sent her on to earn a master’s and doctorate in English literature and linguistics at Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. But it was Holy Child Jesus School and the sisters there who put her on path to religious life and also made her an outspoken and lifelong advocate of Catholic education.

She returned to Mississippi in 1978 to care for her aging parents and was recruited there by Mississippi Bishop Joseph Brunini to develop outreach to nonwhite communities and to develop intercultural awareness programs. This also is the period where she became a national presence as a teacher and preacher.

For all those she inspired with her unique brand of preaching, often mixed with song delivered in an exquisite voice, her most enduring legacy may be her support of Catholic education, and particularly education for disadvantaged African Americans.

______

Mary Lou Jennings was one of four on a panel whose members exhibited Bowman’s ability to inspire in (or wring from) others possibilities they’d not before imagined. The 74-year-old Jennings has headed the Sister Thea Bowman Black Catholic Educational Foundation for the past 25 years. Like Bowman, she defies categories and boundaries. She was heavily influenced by Jesuits and Ignatian spirituality beginning in elementary school in Miami, Florida, and continuing through Georgetown University in the 1950s, where she earned a bachelor of science in nursing, one of only two disciplines open at the time to women. Jennings earned a liberal arts degree and most of a master’s in French and fit in three years of classical Greek at Michigan State University, studied theology at St. John’s College in Minnesota, and also studied spirituality over five summers at Fordham University, all the while raising four children with her husband, Len, an orthopedic surgeon (now retired).

Much of that biography plus a friendship with the late Bishop Kenneth Untener of Saginaw Michigan, one of the most liberal U.S. bishops in recent memory, would, in the usual run of such things, place her on the progressive side of the Catholic ledger. At the same time, Jennings describes herself as a pietist with a deep devotion to St. Pope John Paul II. She is a regular reader of First Things, the conservative Catholic publication, and finds inspiration in one of its principal writers, the neo-conservative George Weigel. In that rather eclectic mix, Jennings may be illustrative of one of Bowman’s hidden contributions to the state of the church: Bowman really didn’t abide by boundaries.

Jennings first met her while attending a session Bowman was leading at the 1984 National Catholic Educational Association meeting in New Orleans. She had been working with Untener in an effort to save an all-black inner-city school that was in danger of closing for lack of diocesan funds. She and her husband at the time were also sending a young African American woman through Catholic University. But when she and the bishop and others involved got together to write a philosophy for the elementary school, only white faces gathered around the table. “I said, ‘How can we do this? We’re not black.” Untener agreed and told her to go meet Sr. Thea.

The Jennings, she recalled in an interview with GSR, were the only white people in the packed room. Bowman came prancing in, singing “in this operatic voice. I had never seen anything like it,” said Jennings. And everyone joined in. People stood and they took out white handkerchiefs and began waving them above their heads. It was an example of what she meant when, during that later speech before the U.S. bishops, Bowman would tell them that being multicultural meant “sometimes we do things your way, sometimes we do things mine.” Multiculturalism for her meant more than getting along, and in no way did it mean erasing differences.

In a talk during the 1980s to members of religious communities, Bowman said trying to understand diversity by saying, “We’re all alike” is counter-productive. “If I say, ‘We’re all alike,’ I’m saying, ‘I don’t need you. You know what I know and I know what you know, and I don’t need you.’ But we’re different. We don’t look alike, we don’t walk alike, we don’t talk alike, we don’t play alike, we come from a different history, a different past, a different experience.”

In that room in New Orleans, those differences from the majority white church were clear.

“I didn’t even know what they were doing,” said Jennings. “The room was just filled with her. You know how some people light up a room? She did more than light up a room. She turned them on. She just came in and sang and then she preached. She said, ‘I’m here to catechize you, and I only know how to do that through beauty and song and music and dance,’ and she sang again. All the children joined her. That’s when I first met her.”

Jennings approached Bowman after her presentation, “And I said to her that I had done a little work with African Americans and at that time Len and I were putting a young African American woman through Catholic University.”

Jennings told her that she had come on behalf of Untener and described the project and then said, “But I’m not black.” Bowman replied, “You certainly aren’t.”

And Jennings recalls saying, “I don’t know anything about African-American consciousness.” Bowman didn’t hesitate to confirm her. “You’re right, you don’t know anything,” she said. “You need to come to Mississippi.”

“She didn’t say, ‘Oh isn’t it wonderful what you and your husband are doing.’ Oh, no,” said Jennings, laughing. “She said, ‘You come to Mississippi.’” So went the somewhat testy start of a relationship that would endure into a deep friendship. But Jennings admits now that at first meeting, “I didn’t really like her.”

Often, said Jennings, she felt as if Bowman was testing her. During one of their early meetings, Bowman told her, “White folks come down here all the time and say they’re going to help, but you never see them again.” The determined Jennings took the comment as a challenge, and whether Bowman knew it or not, there would be no getting rid of her new acquaintance.

Jennings went to Mississippi repeatedly, though often feeling competing emotions: on the one hand, that she could do nothing quite right in Bowman’s eyes; and, on the other hand, driven by Bowman’s insistence that what she and Len were doing locally – supporting disadvantaged African American children through school and college – had to be done nationally.

“I told her I wanted to be a theologian,” Jennings said. “She told me, ‘You can do that in your next life.’”

The Jennings spent a significant amount of their own funds over the years bringing Bowman’s ambition for a national organization to fruition. Mary Lou never took a salary from the foundation, and Len’s work subsidized her travel expenses. Along the way they began picking up support from other individuals and groups. A priest at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, where the Jennings were supporting a student at a time when Jennings was considering giving up her work with the foundation for lack of funding, set up a fund-raising event that included members of the Rooney family, owners of the NFL’s Pittsburgh Steelers. The team has provided support in various ways for the past 20 years. The Knights of Columbus provided a major donation for foundation work and regular annual donations to pay for housing and child care for single mothers attending college.

Mary Lou was with Bowman for periods toward the end of the nun’s life, during a time when the Jennings were living in Vermont. One of Bowman’s last visits occurred in October 1989, as the foundation took shape as a formal entity.

“She was very sick at the opening of the foundation,” recalled Jennings. “I went into to see her. She said, ‘I’m dying.’ I said, ‘I know.’”

Bowman told Jennings she had to keep going, that the foundation had to go national and help more African American students. Jennings told her that she didn’t think she could go on without Bowman. The racial reality was raised. “I’m not black,” said Jennings, who recalls that Bowman replied, “You’ll be okay, you’ll find the people that you need to help you.”

There was also the matter of their own relationship, at times prickly. “Don’t get me wrong, there were times when she was nice to me, and we laughed and had fun,” said Jennings, but she felt exhausted and frustrated, still inadequate to Bowman’s expectations.

“I started to cry,” said Jennings. “I just couldn’t seem to ever do anything right for her. But then she asked my forgiveness for all of that. ‘I want to ask your forgiveness,’ she said. And she took my hand. She started to cry, and she said, ‘You are my sister,’ and she prayed, ‘Lord make us closer as sisters.’ It was beautiful.’”

It was the last time the two would see each other.

In the intervening years, the foundation has put more than 150 African American students through college. Jennings said the organization is now attempting to transition to a more structured form. It is time, she said, to look for her replacement and to include more African Americans on the board. She said she also hopes to see the foundation move out of her home in Duluth, Minnesota, to either Chicago or Washington, D.C., where there is a greater African American presence.

______

Br. Mickey McGrath, a member of the Oblates of St. Francis de Sales and an artist, writer and speaker from Camden, New Jersey, never met Bowman, but she inspired a significant change in his life.

He first encountered her as he was visiting his dying father in his Philadelphia home. While his father napped, McGrath picked up a copy of U.S. Catholic that contained Bowman’s last interview.

“I read this, and I was in tears because she talked about going home.” She didn’t talk about dying, but said, “I’m going home. I prefer the language of my slave ancestors. I’m going to meet Jesus. I’m not looking forward to pain and suffering. I’m not a martyr or victim. But I look forward to meeting Jesus.”

McGrath said the words filled him with hope as he looked up at his father. About a month later, his father died and McGrath realized that after 11 years of teaching art at De Sales University in Center Valley, Pennsylvania, he needed to concentrate on making art.

He began painting, but none of it pleased him. And then some friends invited him to view a video of Bowman. The next morning he began painting images of her in a manner and style he’d never used before. He painted for weeks and “nine images emerged.” And she became one of his favorite subjects. McGrath, who provided a new painting, of Bowman with St. Francis of Assisi, for the observance here, said he believes something mystical happened in that second encounter with her.

“I thought, ‘I have a little black nun inside of me and I really feel she possessed me.’” Soon he was doing exhibits of his work featuring images of Bowman, who introduced him “in a new and challenging, fresh way to Salesian spirituality. . . . I was feeling like a 35-year-old orphan wondering what I was going to do when I grow up, and she led me to it.” She convinced him, he said, “that the world doesn’t need any more bad landscape painters. The world needs what you can bring to it.”

______

Striking similarities exist between the lives of Fr. Maurice Nutt and Sr. Thea. Nutt is executive director of the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University in New Orleans, which Bowman helped to found in 1980. A native of St. Louis, he was 13 when he left an inner-city housing project, inspired by the Redemptorist priests who ran the parish he attended, to enroll in the order’s seminary high school in Edgerton, Wisconsin.

Unlike Bowman, however, after nine years of formation and final vows, he said, “I had assimilated into a Germanic-like, cold culture. I wanted to be the best Redemptorist I could be. My collar was right, my habit was pressed, my rosary beads lie just so. I had a desire to say that in order for me to be religious, I had to forget all of that back stuff. I had to assimilate I had to let them know I fit in.” He said he had told himself, “I’m going to be the best white religious I could be.”

He met Bowman when he attended the first Institute for Black Catholic Studies graduation in 1984. She was commencement speaker. He can no longer remember the specifics of her talk, and she was not much for documenting such things, so Nutt has been unable to find the content of that speech. “But it was a cathartic moment for me.” Whatever she said became for Nutt “a moment of revelation, a moment of epiphany. Whatever she said, it opened up the floodgates. And I cried uncontrollably. She spoke to my heart. She said to me, ‘Maurice Nutt, you can be the best Catholic religious you can be, the best Redemptorist, but you can also be who you are, an African American man.’”

He now calls her his “spiritual mother.” Along the way, she was his teacher (Preaching I, Preaching II and Black Religion and the arts, he recalled). He considers her “the patron saint of racial reconciliation.”

______

Sr. Marla Lang, a La Crosse classmate of Bowman’s, said she couldn’t imagine how difficult it must have been 25 years ago for the young woman from Canton, and how difficult it continues to be for African-American women in leadership. “Not all went smoothly, and not all actions were affirmed” at the time, a period when religious orders in general “were working through the ‘re-making questions’ we all had within us.” But she recounts Bowman’s words, looking back on her career, acknowledging that the FSPA community gave her “a religious identity as well as a platform from which to speak as a well-educated person.”

Bowman recalled the FSPAs “who have loved me and who have believed in me; who have encouraged me, who have challenged me to do and be my best, who have walked with me when times were troubled, who have understood – these sisters have enabled me and, actually, that is what FSPA has meant in my life.”

And then she added a thought for her community that might well apply in the wider church and beyond. “I’d like to say I’m sorry for the times I haven’t connected properly,” she said. “I’d like to say that there is still hope that we can still be good news for one another.”

[Tom Roberts is NCR editor at large. His email address is troberts@ncronline.org.]