When 13-year-old Sheila Flynn decided to attend a weekend youth camp on the fringes of the Epping forest in Essex, England, she and her friends expected a “wild weekend” of fun. Instead she was introduced to the philosophy of St. Dominic.

“I was exposed to this man whose pursuit for truth and his incredible compassion just seared my heart,” said Flynn, who would join a community of Dominican sisters, “and I knew that was what I would become.”

It was a vision that eventually brought the Irish native to South Africa via the United States. And it was in South Africa that Flynn was permitted to fulfill a long-held ambition to study art and share her natural talent with people who needed tools to heal and lift themselves up.

Flynn realized that she wanted to help impoverished women when she offered a ride to two women standing on the roadside during a drive from Durban to Johannesburg. They refused, saying it was not her “kind” of lift they needed and she realized they were sex workers, plying their trade among the thousands of truck drivers who travel the 301-mile (500 km) route each day.

Having read reports of the high number of truckers who use prostitutes while working, she gently asked if they appreciated the risks they were exposing themselves to. She was deeply moved when asked in return if she knew what it is like to hear your child crying from hunger at night.

Overcome by the circumstances that dictate what a mother needs to do for her children, Flynn decided to find a way to use her skills to help women facing grinding poverty each day. She and a colleague, Sr. Mary Tuck, also a Dominican, started looking for an income-generating project for women.

Their answer: Kopanang Community Trust, launched in 2001.

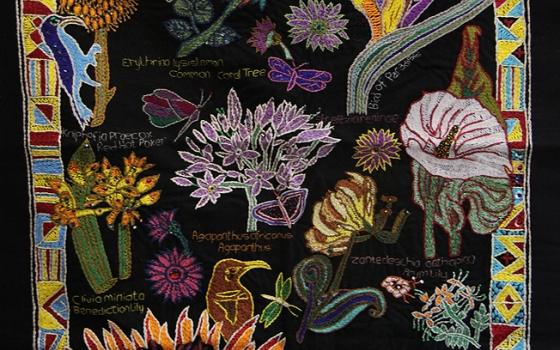

Kopanang, is a Sotho word for “gathering together” and the name of the hopeful center where women come together to create works of embroidery, and to share their stories, their problems, their courage and their solutions.

All of the Kopanang women are either living with HIV/AIDS or have close relatives who are HIV-positive or who have died from AIDS. Many also suffer abuse at the hands of their intimate partners. All live in deep poverty.

“Here at Kopanang we grow spiritually and emotionally,” says 50-year-old Beauty Mabunda, who has been a member of the Kopanang community since 2006. “Before I didn’t believe in myself, but now I have the strength for whatever I come across [in my life].”

Mabunda also participates in Dikaledi (Sotho for “long tears”), a support group for working through problems with a therapist.

The group finds solace in the traditions of the Bible, Mabunda said. “We share different stories among those women and we find the [baggage] that you have at your home lighter than before because of the comfort, the love, that we get from the women.”

Kopanang is in Tsakane, a township 34 miles (55 km) southeast of the sprawling metropolis of Johannesburg, in an area known as the East Rand.

Like other black townships throughout South Africa, Tsakane was developed in the apartheid era for people working in areas designated as “for whites only.” (Apartheid laws were draconian measures designed to keep black South Africans separate and oppressed; they were prevented by law from performing anything other than menial jobs.)

Residents of these townships did not have electricity, running water and proper plumbing in their homes. The townships were built far from people’s workplaces, so transportation was inadequate and costly for the residents, who had to leave very early for work and returned very late.

Tsakane now has basic services, schools, a hospital, a police station and paved roads. It is a fast-growing township, with many modern, if modest, homes, and there are many residents now with decent jobs. Even so, grinding, jobless poverty is a fact of life for many more.

But the women of Kopanang, previously unemployed and often unemployable, are now able to earn modest incomes through their embroidery, and they also access training in leadership, computers, driving and other skills.

Patience Nomonde, a single mother caring for three children and two grandchildren, has been part of Kopanang since it opened. With the embroidery she has stitched and sold there, Nomonde first was able to add windows to her home and is now adding another room.

Even her first meager paycheck made a difference.

“When I started working in Kopanang I earned R59.00 (U.S. $5.90),” she said, “and I was so happy for that R59 because I could buy a packet of sweets for my children, a packet of candles – I was using candles for light – and there was something to put on the table for my children.”

In 2008 she became ill. Nomonde says a workshop on HIV/AIDS at Kopanang empowered her enough to ask for voluntary counselling and testing.

“So the doctor said, ‘Can I have somebody to help you?’ The lady came, and we sat and she said to me, ‘If I can tell you results, you are HIV positive, how would you feel?’ I said, ‘I am ready.’”

Flynn has been at her side ever since.

Nomonde knows how to work with her body and the illness, Flynn said, “and she has been such a witness of hope,”

“She wasn’t going to die,’’ Flynn continued. “This wasn’t going to take her off.”

The embroidery made by the women of Kopanang is sold locally and internationally, not only to provide an income for the creators but to ensure sustainability of the project. Sixty-six percent of the money goes to the maker and the rest goes back into the project to purchase supplies.

The project has also spread its mission to Australia and the United States by inviting students from those countries for annual ‘immersion’ visits. The students are hosted by the women of Kopanang, live in their homes and share their daily lives and meals.

Because the students pay to participate, the program generates funds for Kopanang while also publicizing the project in the students’ countries. The impact on students is profound, with many shifting the focus of their studies from commercial to social subjects.

Lena Melshem of Santa Sabina College, a Dominican day school in Strathfield, New South Wales, said in an email she learned about the impact of poverty and the true face of God as a participant in the immersion program.

“God is truly at work in Kopanang, you can feel it in their song, prayer, words and actions,” she wrote. “The women’s lives have been changed by the project and the immersion experience allowed me to develop as a person, and appreciate what really matters in life. Love, faith, family and relationships are what truly are of the utmost importance.”

The Kopanang Community Trust has survived for more than a decade, quite an uncommon feat when many similar projects, some funded by the government, fail quite quickly. Flynn attributes this success to building the project on relationships rather than money.

She only accepts financial assistance from smaller donors if she is sure the purpose of the donation can be achieved, Flynn said. And strong relationships with the donors are established and maintained by regular communication, including financial and progress reports.

Flynn also said women in project have important links with the project leaders and among themselves, and that any problems are immediately addressed.

“We work particularly with conflict resolution. If problems start emerging, Slindile, [a project leader] is a wonderful motivator: she will find some article, some poem, or scripture that will hone in on malfunction, and also have a chance to say how this is happening.”

Flynn said she believes the project is now sustainable, and will continue when she no longer is available. The center helps the women develop confidence and and skills and this year they are being asked to step into leadership roles to help insure the long-term sustainability of the project.

Kopanang is a small life buoy in an ocean of need, Flynn explained. But for each of the women who have improved their lives through participation, it has made a world of difference.

[Delia Robertson is a South African writer and editor who covered southern Africa for Voice of America for three decades.]

Related - Learn more about Sr. Sheila Flynn in Sharing her art by Delia Robertson