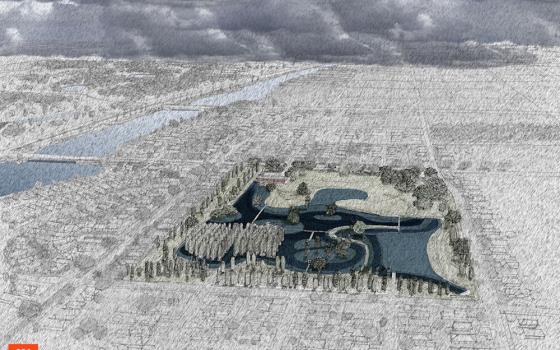

In topographically challenged New Orleans, where "running water" can be a pejorative depending on whether it is flowing inside or outside the house, a long-promised, 25-acre stormwater management and flood control project called the Mirabeau Water Garden will be a welcome sight.

After eight years of design discussion and government delays, the ambitious project made possible through the vision and generosity of the Sisters of St. Joseph appears ready to start.

The garden will be able to store 9.5 million gallons of water in a park-like setting and then slowly release it back into the city’s overtaxed drainage system.

David Waggonner, the project’s lead urban and environmental architect, is eager to see how the water retention area on the Mirabeau Avenue site where the Sisters of St. Joseph’s motherhouse stood before Hurricane Katrina, will transform both the hydraulics of the surrounding area and, more importantly, the deeply held view that the only solution to keeping the city safe from flooding is to pump water out of the New Orleans bowl.

"The sisters were way ahead — maybe because their faith lets them move forward," said Waggonner, the founding principal of Waggonner & Ball. He first approached the Sisters of St. Joseph in 2011 when he heard they might be thinking of making their land available for the project.

When the motherhouse took on 7 feet of flooding from Katrina in 2005 and then was struck by lightning and gutted by fire in 2006, the sisters prayed about what to do with the large and mostly undeveloped site they no longer needed. As New Orleanians began returning home from the Katrina diaspora, the sisters easily could have sold the undeveloped parcel for millions as homesites, using the money to provide for the retirement needs of their aging members.

Instead, after meeting for months with Waggonner and latching on to his vision about working with the environment to manage water, the sisters decided to jump-start the project by leasing their land to the city for $1 a year, a monumental step on the way to securing funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency and other government entities to construct the garden.

"We could have sold the property 15 times to this day," said Ed Sutoris, who oversees the congregation's properties from his office in Chicago. "Every two weeks someone is calling me. It probably was worth about $2 million-$4 million. But the sisters' definition of 'best use' was this project."

"This caught the heart of the sisters because if they could show that this 25-acre parcel could protect thousands of surrounding acres, then that would be big enough proof to encourage other landowners in New Orleans to do something similar."

"Actually, we kept vigil with that land, praying that some idea would come to us that would help the land serve the people of New Orleans, just as our sisters had done all those years," said Sr. Pat Bergen, the former congregational leader, who lives in St. Louis. "When David approached us with this idea, we initially knew this is what we were praying for," she told the Clarion Herald, archdiocesan newspaper of New Orleans.

Waggonner said construction is expected to begin by the end of the year.

The major phase of the $20 million project — the gross water storage features — will cost about $13.2 million and is expected to take 14 months to complete. The second phase calls for the construction of educational buildings by 2022. The buildings will be used to teach students and others about the science of water management and how the site's newly planted cypress trees, shrubs, flowers and grasses will help create an ecosystem that can mitigate flooding.

The site will have stormwater features to store and filter water and allow it to "infiltrate" the ground. Excess water will be released back into the drainage system. The site also has a planned reflection area commemorating the Sisters of St. Joseph for their commitment to the project and to the people of New Orleans.

A. Baldwin Wood's "world-class" invention in the early 1900s — the screw pump that could lift large quantities of water — drained large parts of previously uninhabitable New Orleans, Waggonner said, but that engineering breakthrough came with "a tradeoff."

"The part that was not factored in was the subsidence," Waggonner said, referring to a gradual caving in or sinking of an area of land.

"The pumping of shallow groundwater was not understood as the cause of subsidence," he explained. "Because of the way we've constructed our drainage pumps — with open joints — and because we put these big suction pumps on them, you're constantly dragging down the groundwater, which is dragging down the land. So, we're actually sinking the city by pumping it. This system has a radical cost, an unsustainable cost."

For now, Waggonner is buoyed by his collaboration with Dutch groundwater expert Roelof Stuurman, who has stressed the need for innovative water management areas in New Orleans, and with the Sisters of St. Joseph.

"It's always been a matter of trust with the sisters," Waggonner said. "And, in this case, perseverance, because it's been years."

Bergen agreed.

"The need is visible and apparent," she said. "All of us sisters are praying that movement will happen on this adventure quite quickly because we see its potential — and its hopes for the people of New Orleans."