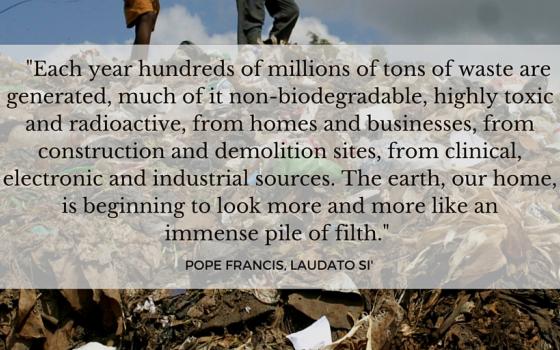

Global Sisters Report is publishing a special series about how trash is managed in the world and how sisters are helping people affected by landfills. We start this project to mark the one-year anniversary of Pope Francis' encyclical, Laudato Si', about climate change, pollution and waste, which warns that: "The Earth, our home, is beginning to look more and more like an immense pile of filth."

______

Sodom and Gomorrah has 100,000 residents and no schools.

The infamous slum in the south of Ghana's capital of Accra is actually Old Fadama, but everyone outside calls it Sodom and Gomorrah. The illegal urban settlement is a crowded maze of ad-hoc buildings where transplanted refugees from Ghana's severely underdeveloped northern region live. Sodom and Gomorrah is its derogatory nickname for people who think the slum is filled with crooks, junkies and prostitutes.

The government refuses to build schools, or barely any permanent infrastructure, in Old Fadama, because it is an illegal slum that they hope to raze to the ground. The residents have no rights to build on the land, and the government has threatened to evict them, even bulldozing parts of the slums last July.

Old Fadama is internationally famous for the Agbogbloshie electronic waste dump, where men and boys spend their days breaking apart the world's e-waste by hand and burning the parts down to salvageable metals. The photos of this process have made their way around the world, prompting outrage.

But the residents of Old Fadama don't want your pity. People who call it an e-waste "dump" are just as bad as those who use the nickname Sodom and Gomorrah, they say.

"You can make harsh judgments about these people, but when you get into the families and see their struggles just to get to the very basics of survival, you start to understand," said Sr. Eileen McGrath, a Franciscan Missionary of Mary who acts as an informal social worker in Old Fadama to encourage parents to pursue educational opportunities for their children.

They don't need pity. They need schools.

An hour-by-hour economy

People in the rest of Accra believe the slums are full of crooks or people too lazy or unintelligent to raise themselves out of dire poverty. Few local Ghanaians venture there, and even sisters who have been working in Accra for decades have never set foot in Old Fadima.

But in reality, the slums are a hive of activity, an informal economy that has transformed a pile of electronic waste into a lively market supporting thousands of people.

Old Fadama embodies a poverty hard to comprehend from the outside. You don't buy a tube of toothpaste, because that's too expensive, but you buy a squirt of toothpaste each day. You don't buy a costly nail clipper, but someone has a business to walk around and cut people's nails for a few cents.

Few people have enough room to cook in their shacks, so they buy all of their food from the local women who cook in the alleys. Want a drink of water? There's no potable water here (or in all of Ghana), so a plastic bag of water called a water sachet is 20 pesewas (U.S. 5 cents). Need to go to the bathroom? The government doesn't recognize this slum, so there are no public services, like latrines. Toilets are a business just like anything else. It'll cost you 30 pesewas to use the toilet, 50 pesewas (13 cents) if you want a door on the stall. A shower is 50 pesewas, extra if you want more than one bucket of water.

Want electricity in your shack? The power company doesn't reach here, but you can pay an exorbitant amount to someone with a meter, who will hook you up to electricity but charge far above the market rate because there is no other option.

People in Old Fadama don't live day to day. They live hour to hour, always hawking something so they can scrape together the next few cedis for a meal.

Career paths are almost carved in stone: Men and boys go to the e-waste market, finding a niche item they can break apart and sell or burn to sell the metals. Girls work as head porters in the tomato, yam and onion market next to the slum. As they get older, the women ply their own wares with buckets perched on their heads, items like soaps or fish perfectly balanced and towering into the sky as they weave through traffic on the main roads outside the slum.

This constant financial limbo perpetuates poverty. While people struggle to plan for the future, they buy in the smallest quantities possible, paying the most expensive price. Meanwhile, the cost of goods keeps going up, and it becomes impossible to stay afloat.

A way out

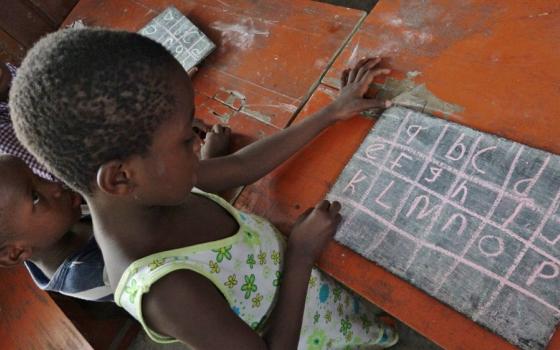

The way to break this cycle of poverty is through education. But how do you educate thousands of children when there are no schools?

"There are some private schools here but they're not meeting any requirements," explained Abdallah Alhassan, 27, a leader of the Slum Union, an advocacy group started by Amnesty International that works to organize members of several Accra slums and change public perceptions.

Most of the "schools" in the area are thinly veiled businesses, charging tuition for students and not making any effort to educate them. When we walked to some of the private "schools" deep in the slum, people started yelling at us to put away the cameras, refusing to speak to reporters.

By day, children mill around the neighborhood, kicking a ball of tightly wound rags or jumping over ditches. Even on a weekday afternoon, none of them are in school.

"Outside the community, in other neighboring communities, they have government funded schools," explained Alhassan. "Those children who have parents that care, they go to the government schools, but it's expensive to take a bus or it's a very long walk."

The challenge is that parents need to fully appreciate the importance of education in order to make that enormous effort to obtain it for their child.

"If parents don't get a feel for the importance of school, it won't be sustainable," explained McGrath, who has spent more than a decade visiting individual families in Old Fadama to counsel them about getting an education. "It becomes a partnership, gradually they begin to get more involved so things continue."

McGrath, originally from Ireland, works with Fr. Subhash Chittilappilly, an Indian Missionary of Charity priest, and the two are the only church employees serving the population. Chittilappilly runs the City of God school, an informal preparatory and adult education school located deep in the slum.

Each year, McGrath identifies a "class" of students ages 9-13. She works with their parents or guardians, visiting on a regular basis to advocate for education. Chittalappily holds daily classes for these students, teaching core subjects like math and English, as well as discipline and order. The classes are not certified by the Ghana Educational Service as a recognized school. Instead they are meant to prepare students to enter government schools by the coming September.

"To pick them up from the streets and put them in school is very difficult," explained Chittilappilly. "So they come here for a year, and we talk to the parents. Otherwise it's very difficult for them to adapt."

Every evening, from 7:30 to 9:30, the City of God school holds literacy and English classes for 60-70 adults. The school had a program to teach beadworking to people working as prostitutes, but it failed because the earnings couldn't compete.

McGrath tries to find opportunities to help some of her charges get a vocational education. But even that can be difficult, because she must balance the need for an education with the residents' need to work to make money for survival.

"I had to go to negotiate with a woman who is teaching hairdressing, to let this girl go out and do marketing [selling on the side of the road] for a few hours a day because otherwise she won't have any money to eat," said McGrath.

The leading industry

McGrath and Chittilappilly are also fighting an uphill battle against the pull of the Agbogbloshie e-waste market, which is the main economic engine of the area. People working in the market can earn up to 40 cedis ($10) on an average day, compared with approximately 15 cedis (less than $4) for a day of selling things on the side of the road.

From a distance, the area next to Old Fadama that hosts the Agbogbloshie e-waste market looks like a dump. There are piles of trash everywhere, since there is no organized trash removal. Fires burn 24/7, as people involved in recycling burn the electronic parts and plastic-coated wires to extract metals such as lead and copper.

Burning the broken electronics to extract metals brings a host of health problems, releasing toxic chemicals into the air and causing respiratory distress.

"Some people call it an e-waste dump, but it's not a dump," explained Alhassan. "It's important to say that at the market we do buying and selling. Normally, it's portrayed as we just get it."

The electronic items at the e-waste market, even the broken ones, are purchased somewhere along the line, either directly from the port or from homes and businesses in Accra. The common misconception is that the electronic waste is dumped in a pile somewhere in Ghana and people scavenge. Instead, as Alhassan and others want the international community to understand, it is an intricate economy of buying, selling, trading and marketing that supports thousands of people.

More than 1,000 people are directly involved in breaking apart the electronics by hand, says Alhassan, who worked there from 2007 to 2012. Although Old Fadama predates the e-waste market, the economic opportunities have caused the slum to grow much more quickly, attracting thousands of people from Ghana's underdeveloped and isolated northern regions.

A Greenpeace study examining electronic waste at the Agbogbloshie market found that children as young as 5 are sent by their parents to break apart the electronics. Men and boys sit on the side of the road with rocks, chipping at computers, refrigerators, air conditioning units and fax machines. Thousands of others are involved in other aspects of the e-waste trade, including coordinating collection points or traversing the city by foot to find old electronics. Others patrol Ghana's ports, where containers of old electronics arrive on a daily basis from Europe.

The electronics that are shipped to Ghana are a major point of contention. It is illegal to export e-waste from Europe, so unscrupulous traders classify the shipments as "second-hand products" that they claim can still be fixed. This shady reclassification is utilized because it is cheaper to export e-waste to Africa than to safely dispose or recycle it in Europe.

According to Greenpeace, up to 75 percent of the second-hand electronics that arrive in Africa are not fixable or appropriate for resale.

In 2014, the United Nations University, a Japanese think tank that focuses on solving the e-waste problem, estimated that the world produced almost 42 million tons of e-waste that year. And this amount is growing exponentially: In 1997 the average lifespan for computers in developed countries was six years, but in 2005 it had already dropped to just two years, according to the U.N. Environment Programme. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that e-waste will increase by 5-10 percent each year, so a solution for what to do with these discarded products is imperative.

In 2013, the Ghanaian government banned the importation of second-hand refrigerators, but later that year they uncovered a shipment of 37 containers filled with 4,000 old fridges from the United Kingdom.

"If we knew we could dump all of our trash on Europe, we'd do it too," said Alhassan.

Another person's treasure

The Greenpeace study found that samples from the ground in the Agbogbloshie e-waste market contained toxic metals, including lead, in quantities as much as 100 times above other areas of Accra. Other chemicals in the area included phthalates, some of which interfere with sexual reproduction, and chlorinated dioxins, which are carcinogenic. During the rainy season, Old Fadama, which was built on wetland ("Fadama" means "mushy" in the Hausa language) often floods. The ground chemicals are then swept into the Odor River and out to the Atlantic Ocean through the Korle Lagoon.

"When you wipe the sweat off your body, it comes off black," said Chittilappilly. He said that many of the children have skin diseases and asthma but there are also no clinics in the entire slum, just for-profit pharmacies that may not have trained medical professionals. Chittilappilly, who said he often got sick when he first started working in the slum but has now built up a resistance, hopes one day to have a small clinic supported by the church.

As stated earlier, the residents of Old Fadama working at the e-waste market don't want international pity. After other global media coverage has portrayed the dump in an ugly light, journalists and researchers wielding cameras are no longer welcome in the area where the breaking apart and selling take place, said Alhassan, because they are perceived as endangering livelihoods. "Yes, we agree that it's dangerous, but people have no choice, as much as it's destroying the environment," he said.

There is almost a quiet pride among residents that people in Old Fadama have figured out how to make money from something the rest of the world sees as trash, creating employment for thousands of people out of thin air.

"People here see it as an opportunity to have jobs, that's how I saw it," said Alhassan. He is one of the few people able to escape Old Fadama: He used the money he made at the e-waste market to go to the University of Ghana, where he graduated in 2012 with a degree in business management. After a decade living in a rented shack in Old Fadama, he moved earlier this year to a permanent neighborhood in Accra and is still involved in advocacy for his former community.

"If we stop, your house will be an e-waste dump," said Alhassan. "They say we get cancer, but I don't know anyone who suffered from cancer. Sometimes they find a way to exaggerate stories."

"The media in Ghana portrayed all the slums as a very negative thing, and everyone living there is a criminal," said Alhassan, who runs a charity with his friend Faidal Rahman, 28, to help pay for school fees for local children and a community center, in a similar initiative to the City of God school without the organized preparatory year.

"There are good people and bad people all over the world," said Rahman, who still lives in Old Fadama. "Here, we don't have public toilets or schools. If we had those resources, they wouldn't say bad things about us. People are here because they have no choice."

For Alhassan, who did not participate in the City of God school, education was his ticket out of the slum, just as McGrath is desperately trying to convince the parents. It took him six years of breaking apart fridge motors (they contain both copper and lead) to save enough to begin his degree. Alhassan had an advantage, having completed high school at home in the northern part of Ghana before coming to Accra to make money to continue studying.

"It's all about perseverance and vision," Alhassan said. "So if you are interested in education, it may mean you need to stay hungry for some days or only eat once a day to pay for a book or to pay your school fees. But because if you believe that the future is education, you do it hoping that soon times will change."

[Melanie Lidman is Middle East and Africa correspondent for Global Sisters Report based in Israel.]