Global Sisters Report is focusing a special series on mining and extractive industries and the women religious who work to limit damage and impact on people and the environment, through advocacy, action and policy. Pope Francis last year called for the entire mining sector to undergo "a radical paradigm change." Sisters are on the front lines to help effect that change.

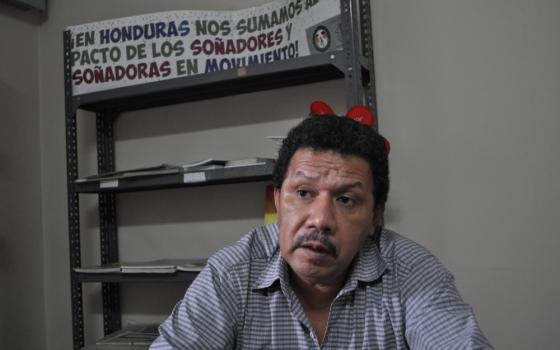

Environmental activist Pedro Landa knew fellow activist Berta Isabel Cáceres for 20 years.

They had walked together for so many years he recalled from an office of Radio Progreso in this traffic- and billboard-clotted city. They had dreams of building a society based on equal justice for everyone.

"We were like family," Landa said. "She always called her friends 'compas' and 'compitas.' She always wore blue jeans and boots. She would never wear a dress or a skirt. She always worried if the people with her had something to eat. She carried bags of tamales so everyone had food. No matter what, she made a point to stop so everyone could eat."

The assassination of Cáceres on March 2 shocked all of Honduras, but it sent a specific message to environmental activists: Even internationally renowned environmental activists are unsafe in Honduras.

"Berta's death was a declaration of war by the government," Landa, 54, said. "We are coming after all of you."

But the effort to intimidate activists extends beyond environmentalists, said Jen Moore, with Mining Watch Canada, an advocacy and research group investigating mining conflicts in Central America.

"People fighting for their land, journalists, LGBT rights activists, anybody speaking up is at risk," Moore said. "The fact that Berta could be killed, Honduras has shown so much indifference. Things were already bad but now they are spiraling out of control."

In December more than 200 organizations in Latin America wrote a letter to Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, calling for greater accountability in Canadian mining operations in their countries. Landa's Fundación ERIC was among the signers.

A commemoration for Cáceres was held June 15, with about two dozen people congregated outside of the Honduran Consulate in Midtown Manhattan as part of events to mark Global Day of Action Demanding Justice for Berta June 15. Many represented various environmental and human rights groups. Cáceres is seen by Catholic sisters, environmental activists and others as a poignant example of martyrdom for her spirited and visible work in opposing the controversial Agua Zarca Dam, a massive construction project that activists oppose because of its possible damage to the Gualcarque River, a body of water held sacred by indigenous groups.

Activists want the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to lead an independent investigation of the killing, which followed years of death threats against Cáceres and other activists for their work in opposing the project, and are calling for a suspension of U.S. military aid to Honduras until the matter is resolved. Some members of the U.S. House of Representatives have introduced legislation to that effect.

Landa, as well known in Honduran environmental circles as Cáceres, said he has received multiple death threats and attempts on his life. In 2008, while he was at a meeting in Tegucigalpa, men with machetes waited outside; in 2010, after he spoke before the Canadian parliament about mining, he received a text message, "We know what you are saying. You are about to suffer the consequences." And in 2013, someone fired into his car when he left a televised debate about mining.

"We are living in a historic moment in our country," Landa said, "and not fighting would mean I was betraying my country and also my community."

Fr. Cesar Espinoza also knew Cáceres. They met when she helped him oppose the Nueva Esperanza mine.

"She had a very gifted way of speaking," Espinoza said. She spoke with unusual clarity and straightforwardness. She was one of those people, when you heard her, you loved her. In a meeting in 2013 she said, 'Let's prepare ourselves because many of us will die. I don't know who in here will be next.'"

Espinoza said he remains under threat and has post-traumatic-disorder.

"I awake feeling nervous," he said. "If I'm driving and a motorcycle comes too close, I am scared. If they can kill Berta, what would stop them from killing me, a little known priest?"

Landa's sister, Sr. Miriam Landa with Hermanas of Our Lady of the Holy Rosary in Nacaome near the mining town of El Tránsito, met Cáceres once, at a rally for indigenous people last year.

"She was very humble and sincere," Landa said. "She was dynamic and cheerful at the same time. She was always doing something."

Caceres' death has only made Landa worry more about her brother, Pedro. She talks to him daily, she said, to assure herself of his well-being. Her activism, she said, does not compare to his. She does not fear for her life, only his.

"All I can do is pray for Pedro," Landa said. "It is very painful that our country is used to all this violence. That it is used to people who stand up for other people getting killed for no other reason than defending human rights. Even within the church there are those who don't support our work defending human rights. This is not normal."

[J. Malcolm Garcia is a freelance writer and author of The Khaarijee: A Chronicle of Friendship and War in Kabul, What Wars Leave Behind: The Faceless and the Forgotten. He is a recipient of the Studs Terkel Prize for writing about the working classes and the Sigma Delta Chi Award for excellence in journalism.]