From her mission deep in Panama's rainforest, Sr. Melinda Roper embraces a human rights focus much broader than the one that thrust her into the international spotlight nearly four decades ago.

Roper was at the helm of the Maryknoll Sisters of St. Dominic on Dec. 2, 1980, when four U.S. churchwomen — two of them Maryknoll sisters — were murdered in El Salvador. She was just 40 when elected two years earlier to lead the congregation, which had missions in Asia, Africa and the Americas and traced its history to 1912.

Under her leadership, the Maryknoll sisters fought for justice, for the churchwomen and for those they represented. At a time when Americans were mostly unaware of the U.S. role in training and financing right-wing death squads terrorizing much of Central America, the Maryknolls awakened the faith community in particular and the country in general.

The churchwomen became a symbol for a system that was repressing and killing tens of thousands of innocents, many simply for the profession of their faith. Their deaths helped inspire Central American solidarity groups throughout the U.S. and a sanctuary movement that gave shelter to refugees fleeing the violence.

Global Sisters Report sought out Roper in Panama, where she has spent the past 32 years building a pastoral community in the remote tropical wilderness of Darién province. Her human rights focus and spiritual growth have expanded to encompass the connection between environment and spirituality.

"I encourage all of us to try to understand more of what science is telling us today. … Science and spirituality are not contradictory but complementary; they're the principles on which the universe functions," she told GSR. "In all of nature and all of the universe, everything tends toward interconnecting and interrelating. Another word would be to be 'in communion' with everything."

Recently, together with other sisters in Panama, she launched a new program called "Web of Life," an educational retreat focusing on faith, science and the ecosystem, which GSR will be sharing with readers in a "virtual travelogue" beginning June 22. First, here is her story.

From Midwest to Mesoamerica: The early years

On many levels, Melinda Roper was not a likely candidate to be a nun. The daughter of a teacher who was Catholic and a union electrician who was not, she grew up in Chicago in "a very open religious culture," going to Mass on Sundays but to public school, so knew nothing of nuns or of religious life.

"I don't know how it occurred to me to go to a Catholic high school," she says of her choice to attend St. Scholastica Academy, a Benedictine school in Chicago. "There's always a part of religious vocation that's mystery — something you're drawn to and you're not even aware of, perhaps. What attracted me was not so much to be a religious but the whole experience of learning how to pray, learning how to reflect."

Still, she couldn't imagine herself as a Benedictine sister. She mentioned this to a sister who said, " 'Let's look around and see what we can find.' She found a Maryknoll magazine and said, 'Maybe this is the kind of thing for you.' "

"As soon as I saw Maryknoll I said, 'There, that's something I would be interested in,' " she recalls. "I think it was the combination of deep learning, being drawn into reflection, into mystery and prayer…and I think to be honest it was a sense of adventure, a sense of the unknown."

The adventure began in 1957, after two years at Michigan State University where she studied physical education. She had always loved the discipline of competitive sports, and she loved the training. Years later, she recalls, that discipline would help her through the hard times ahead.

The academic world, however, wasn't what she was looking for. When she received her acceptance letter from Maryknoll, she took the leap. After formation, she served in various roles for three years, including the sisters' novitiate at Topsfield, Massachusetts.

At 26, she was then assigned to teach in a bilingual school in Guatemala City. She knew very little Spanish and nothing about teaching or children. "I was most surprised when they told me I was assigned to Guatemala — I didn't sleep," Roper says with amusement. "I thought they'd made a mistake."

She jumped in and did it anyway. "The kids got through OK, and I discovered something else about myself, and this holds true until today. That sense of adventure helps one to be very open to new experiences…and that whole thing of, 'Go ahead and try it, see if it works' — that's one of the learnings from sports."

Two years later, she was re-assigned to Mérida, in Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula, where she worked with young teens and catechists. She was still struggling with Spanish and lacked social skills, but she credits the teens with teaching her both.

"They could see right through me; they said, 'Leave your books alone for a while and get involved in life.' And they were right on."

Those years brought a sea change in the Catholic Church. After the Second Vatican Council, the Conference of Latin American Bishops was held in Medellín, Colombia, where it was agreed that the church should adopt a "preferential option for the poor." The idea of forming "base communities" and using Bible study to teach literacy and empower poor people gave rise to fervor within the Latin American church for social change and the movement known as liberation theology.

"It was a very wonderful, very stimulating time to be alive," Roper recalls. She and the other sisters in Mérida would go to Mexico City and Cuernavaca to participate in workshops and return home to try and put them into practice.

But their parish priests were not in agreement. "The long and the short of it was that we were thrown out of that parish, and that was a real crisis for me," she recalls. "I realized as clear as clear could be that as women in the Roman Catholic Church we didn't have a chance; we didn't have a voice; we didn't have a vote; we didn't figure into the decision making in any way. So that was a very stark and painful reality for me."

She returned to the U.S. and finished her degree in theology at Loyola University in Chicago — but the world had changed. "At the time I left, Vietnam had not happened; the whole hippie thing hadn't even started," she says. "Martin Luther King was killed; the Kennedys were killed. The liturgy was in English now, and I didn't know the answers in English. I was like, 'Where am I? What's going on?' "

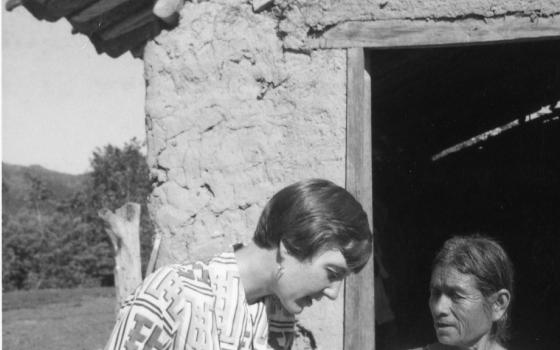

After graduation in 1971, she began a two-year stint in Chiapas, Mexico, with Bishop Samuel Ruíz, who became a dear friend. She learned from his profound respect for the many indigenous groups in his parish, and she studied the Tzeltal Maya dialect and began to understand their community and Earth-centered worldview. But soon she became aware of the escalating violence in neighboring Guatemala and the U.S. role in supporting that violence.

She was asked to become coordinator for the region that extended from Mexico to Panama, and then headed up to the highlands of Huehuetenango, Guatemala, forming leaders and animators of the faith.

"I spent four wonderful years there, and during that time the violence in Guatemala escalated tremendously," she says. "Coworkers disappeared, and there was indiscriminate violence; they were definitely targeting leaders in the church, including some of the people we had trained."

Particularly horrifying was when the Guatemalan government forces got hold of a list of the diocese's health promoters, and one by one they began to disappear.

The diocese began having fewer and fewer workshops. "We didn't want to put people in danger," she says.

As more people fled to southern Mexico, several Maryknoll sisters went to live in the refugee camps with them.

For Roper, it was time to attend Maryknoll's General Assembly, a meeting that occurred every six years to re-elect the leadership and set priorities.

A term marked by pain

The clear and unanimous decision of the 1978 General Assembly was to follow the Maryknoll mission to stand with the poor of Latin America, with all that implied. Roper, with 14 years in Central America, was chosen as president.

"I guess we felt that the Spirit was with us in electing Melinda," says Sr. Jo Kollmer, who served on the board with Roper. "Even in those young years, Melinda had a depth of wisdom and could plumb the depths of some of the things that were happening. … It was her passion for justice and for the poor that really shone through."

It was clear that hard times lay ahead — but no one knew just how hard.

"It wasn't like we walked into anything blind," says Roper. "We knew the implications of the options in Central America, and also in Chile and in Peru."

At the end of the assembly, they made a list of 18 or 19 possible results of their decision. "It said that if we do what we say we're going to do, and live the way we say we want to live, these are some of the things that might happen," Roper recalls. "By the time the six years were over, nearly all of them had happened. On the list was the risk of being killed. That was stated very clearly."

Tensions were escalating, and on March 24, 1980, they exploded with the assassination of Archbishop Óscar Romero as he was saying Mass. It was only nine months later that Roper received the news that their sisters in El Salvador, Ita Ford and Maura Clarke, along with Ursuline Sr. Dorothy Kazel and lay missionary Jean Donovan, had gone missing on their way from the airport. Their burned-out minivan was discovered on the side of the road.

"Right away I knew. They weren't just missing. I knew that they had been killed," Roper recalls. "Of course I was hoping against hope, but in my heart I knew they were gone."

Kollmer, who has maintained a close friendship with Roper throughout the years, recalls the moment clearly. "Melinda's first reaction when we got the news of the sisters being killed was anger, great anger. That anger formed itself into a very good way of expressing what this meant to us."

Another of Roper's close friends, Sr. Linda Donovan, was a novice at the time. She remembers a profound sadness, followed by Roper's words:

"You need to pray, because we know that today in El Salvador to be disappeared is to be found dead. So I need you all to pray."

The next day their worst fears were confirmed when the sisters' bodies were found in a shallow grave.

Donovan will never forget the homily that Roper gave that day. "She was just transformed. You could sense the commitment, the love of the people. It was the injustice of it all, the pain of it all. … I remember her taking the words of the consecration: 'This is my blood, given for you; this is my body, given for you.' You could hear a pin drop."

But there was little time for reflection, as Roper was immediately thrust into the international limelight. There were media interviews, congressional hearings, numerous requests to speak across the U.S. as the nation tried to make sense of it all. When she looks back, she doesn't dwell on the grief. She dwells on the injustice.

"All of a sudden the brutal death of the women was such a shock to so many people, they began to question what was going on there, and what was the U.S. government doing in terms of the violence in Central America?"

For Roper, the role of the Maryknolls was to link the sisters' deaths with the suffering of the Salvadoran people — some 78,000 civilians killed throughout El Salvador alone and hundreds of thousands more throughout Central America.

"We were living in a new age of martyrdom," she said. "It was not just the sisters who had been assassinated. … Thousands and thousands of Salvadorans, of Guatemalans, of Nicaraguans — good people practicing, living their faith — had been eliminated."

Yet her task, as she interpreted it, was not to give a socio-political analysis of Central America. To some degree that was inevitable in order to speak out against the U.S. support of the Salvadoran regime, and to help people understand the violence and why the sisters chose to live — and sometimes die — as they did.

"For me, the message was that living one's faith according to the spirit of Jesus takes one deep into what it means to give of oneself totally for the common good." And that can lead to the ultimate sacrifice — as it did for Christ.

The U.S. government's immediate response was to blame the churchwomen.

"What just amazed me was their ability — and I'll just say it right out — to lie," says Roper.

Jeane Kirkpatrick, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations at the time, told the Tampa Tribune: "The nuns were not just nuns. The nuns were also political activists on behalf of the Frente [the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front]." She later denied saying this until the reporter publicly played back the tape.

Secretary of State Alexander Haig suggested in a hearing before the House Foreign Affairs Committee that the sisters had "perhaps" been trying to run a roadblock — a theory that ran contrary to all available evidence. Called on it, he backed down at a Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing the next day. "He made it up," Roper said.

Roper's words were rooted in the Gospel, and she did not flinch from confronting the lies. Her testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee was clear in criticizing the State Department, which had been "less than satisfactory" in its dealings with the congregation. She called out the investigators on the case for their "lack of communication, defensiveness, evasion and even contradictions."

Five Salvadoran National Guardsmen were convicted of the murders in 1984 and years later implicated military leaders. A United Nations Truth Commission in 1993 concluded that two of the highest-ranking Salvadoran military officers had organized a cover-up. The two, who had been granted U.S. residency and lived for years in Florida, were deported in 2015 and 2016. See timeline for details.

______

The death of the churchwomen was only the most public of the Maryknolls' struggles during those years. A private string of tragedies would engulf the board of directors as well. By the end of Roper's six-year term, of the five original board members when she took office, only she and Kollmer were still alive.

"That whole experience for the congregation was a time of great sadness," Roper remembers. "It was not a time of confusion, although the experience of death being so close and so frequent, and so many of them violent deaths, was something we weren't used to."

Linda Donovan, the Maryknoll sister who had grown close to Roper during her training, had been powerfully affected by the tragedies in El Salvador. Her Spanish was not good enough to be assigned to Central America in the chaos of war, so she was sent to Chile. There the brutal Pinochet dictatorship had already eliminated most of the resistance, and the country was living a dead silence, as she described it. Torture and disappearances were still a reality. Her goal was to be a sign of hope in a place that had none.

In December 1982, two board members, Srs. Peg Hanlon and Gert Vaccaro, paid Donovan a visit. Then on a flight to a remote mission in the north, their plane went down.

"It was horrible — it was just horrible," recalls Donovan. "And it was horrible for Melinda, and we were so far away. I couldn't be present for her like I could have at other times."

She did what she could from Chile. "I was there when their personal things were sent back, I was there to receive the coffins, I was there to put them on the plane."

The very day they died, a third board member, Sr. Regina McEvoy, who was vice-president, was diagnosed with cancer. She struggled for a year and died in December 1983.

"Melinda's time in office was so marked by pain," said Donovan. It wasn't just the three board members; a string of deaths happened during her term, beginning in 1979 with Sr. Carla Piette, who was swept downstream in a jeep in a flash flood in El Salvador along with Ita Ford, who managed to survive. In July 1981, another young sister was struck and killed by a passing car; and a month after McEvoy's death, in January of 1984, two sisters in Bolivia died in another flash flood.

"At one point we counted 16 sisters who had died whose mothers were still alive," Roper recalled.

The mourning of the sisters combined with the public scrutiny was a serious test of their faith. What sustained them, said Roper, was solidarity — from within their own community and the world at large — and a deeper faith.

"It was not a new search in my life," says Roper. "But it certainly got pushed to the extreme in this situation — what really is faith? What helps one to get through?

"Faith is not doctrine, it's not dogma, it's not a list of moral behaviors, of do's and don'ts. That is not faith," Roper says. "For me faith is an energy that comes both from within and without, that helps us see and understand and direct our lives toward something. In my case it would be according to the spirit of Jesus, what he taught … the living spirit of the Gospel, which is also dynamic. It's that living energy, and I can't tell you where it comes from or how it is, how we become more and more aware of it and how we live into that — but I think that's a sustaining thing in my life and it was in those years. And imagine living with a community of women who have that same energy of faith."

Time and time again, it fell to her to find the meaning in the mystery, words to help with the healing. Asked how she did it, she laughs. "I think they carried me more than I carried them," she says of her fellow sisters.

Finding her refuge

The years of public scrutiny and political pressure took their toll, not only on her but on her parents.

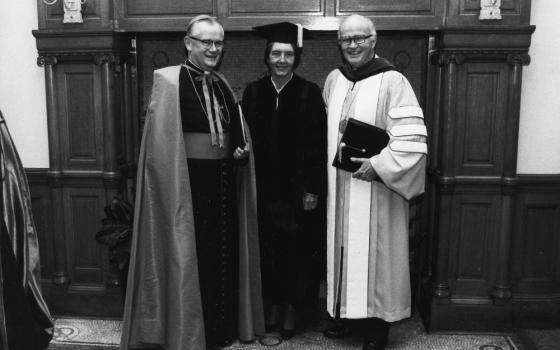

"The criticism was that we were these radical nuns, we were communists, we were not living the Gospel, we were revolutionaries," Roper recalls. When Cardinal Terence Cooke of New York said a memorial Mass for the churchwomen at St. Patrick's Cathedral and invited Roper to speak, the official recognition helped. So did the honorary degrees from Loyola and Fordham universities, Catholic University of America and others. But when she was invited to speak at churches in her native Chicago, the cardinal there forbade it.

"One day my parents went to Mass and the Young Republicans were handing out anti-Maryknoll literature," she said. "So even my poor parents got dragged into this thing."

When her term finally came to an end in 1984, it was time for a major change.

"Was I running, looking for a place to hide? I sure was — there's no doubt about that, and I knew it," says Roper with her characteristic self-deprecating humor, when asked why she suddenly stepped off the end of civilization into Darién, Panama.

"For me, a source of life and inspiration and motivation has been to be with the ordinary folks," she says. "I knew that after these six years removed from that reality, in order to recuperate my energy, in order to help things come together again, I knew I had to get back to the very base level of what it is to live."

She remembered a visit to Panama, when she had met a bishop there, Carlos María Ariz, who "spoke the same language." She contacted him and began discussing the possibilities.

"He said, 'Oh, I think I have just the place for you folks. It's one of the most difficult places I can think of." He was referring to Darién, Panama's swampy badlands that runs down to the border with Colombia.

"Lo que se necesita es una pastoral artisanal," said Ariz: The area needed special, 'artisanal' pastoral care.

She thought about that a lot. "An artisan is someone who looks around and uses the materials at hand and does something very, very practical — but it has a certain aspect of beauty, however rustic it may be.

"When I heard that phrase I really resonated with it. I linked it with that other thing that I discovered in myself — that combination of not knowing what you're going to do or how you're going to do it, but a certain sense of adventure to say, 'Yes, I'm willing to explore, I'm willing to look at that, I'm willing to try.' "

And that's how she and three other sisters ended up in Santa Fe in 1985.

At that time, the tiny settlement was at the end of an arduous eight- or nine-hour journey — "if you were lucky." The road was terrible; there wasn't a church, or even a ranchito to use as a chapel. Once a year or so, a priest would come to baptize the new babies.

"We had to find water, we had to find food; there was no electricity, no communication — it was very challenging and wonderful for me," she recalls. "Just surviving took a lot of our time and energy."

The people living there knew nothing about the civil wars that had been raging throughout the region. "They'd never heard of Archbishop Romero; they didn't know anything about Central America, the violence — that was another world. As Conchita Hojilla, another sister friend of mine, said, 'Oh my God, where are we? This is a whole other situation. Now what are we going to do?' "

The government had recently opened the frontier to settlers, promising 50 hectares to anyone who wanted to stake their claim. They began carving out spaces among the Afro descendants and indigenous people already living there. There was no connection to each other or to the land. Helping to build that sense of community would be a big part of the Maryknoll mission's work.

But it wasn't until the mid-1990s, Roper says, that it dawned on her what was happening: The surrounding tropical rainforest and wetlands were being systematically destroyed — by the logging companies, small farmers and cattle ranchers.

It had seemed necessary to create sustenance for the farmers. But as the sisters learned more about the critical role of tropical rainforests for the health of the planet, they began to pay attention. Industrial agriculture firms had begun to come in and buy out the subsistence farmers and drain the wetlands on a much larger scale.

The Pastoral Center they created began to learn and teach about organic farming, composting, rainwater harvesting and agroforestry. They purchased and preserved a 100-acre forest — the only forest left in Santa Fe, which is now a hub of commerce for the region.

Learning to live respectfully in a complex ecosystem changed their own lives as well, says Roper. Increasingly their emphasis was on wellness — not just of the human community, but also the environment, which they had come to see as integrally connected.

"The ecological crisis is really a spiritual crisis because it has to do with values, with quality of life, with the ability to consider the common good against the individual good," Roper said.

She sees Darién as a microcosm of a planet out of balance, where the human community has lost its sense of itself as a part of a complex and harmonious web of life, to disastrous effect.

"I believe that the alarms that are being set off by climate change are based on scientific evidence; also the disappearance of biodiversity is scary," she said.

While Roper's reflections propel her deep into the cosmos, her feet are firmly planted in the rich tropical soil of Darién. Her impact has spread far and wide — among local families and people like Clara Meza, a Panamanian former sister who, after leaving religious life and raising a family, was inspired to move to Darién three years ago and join the work of the Pastoral Center as a missionary.

"She opened me to life again," Meza says simply. Last year Meza helped with the annual assessment for the Maryknoll office. "People said that the role of Melinda in these 32 years has been to fill people with dignity — and with a great deal of love," she said. "Everyone is known by name; all their problems, everything they feel, what their needs are: 'How is the cow doing? And the pigs? And how are the children?' in a way that people feel part of her family."

Watching her give money to a panhandler: "You ask her, 'Why does she do it? He's a drug addict.' She says, 'No no no no no, I don't care. He needs the money.' She always asks, 'How would Jesus do this?' She has a heart the size of the world."

Roper changed Meza's life with her example, she says, and encouraged her to renew her vows privately. She wrote them alongside Roper, committing herself to the Mother Earth and to God.

For Roper, exploration of the natural realm from a spiritual standpoint has been a fruitful area for reflection.

"They say that the universe is constantly expanding. … And if the universe is constantly expanding, what is God like? It means that God cannot be contained, that God is also expanding and charged with energy and newness…and all the tendencies of many religions is to try to fix God, to try to control God, to make God like a rock or an old man."

In 2015, Roper was invited to speak at the University of Central America in San Salvador, the same university that stood at the forefront of the struggle during the civil war and where, on Nov. 16, 1989, six Jesuit priests were murdered.

Her talk, "Vida: Un Sacramento de Dios. Presente" (Life: A Sacrament of God. Present), discusses that connection in the context of spiritual practice:

"Our capacity to live with a spirit of sacrament propels us towards the galaxies and the universes — and at the same time, it embraces us in the breezes, the waters, the colors and the songs of our sacred Earth. Our capacity to marvel, to question, to study, to learn, to create, to produce, to organize ourselves, brings us to the reflection and the contemplation in the face of the mystery of what we call life."

Come along with Global Sisters Report to the Web of Life eco-spiritual retreat in our virtual travelogue beginning June 22.

[Tracy L. Barnett is an independent writer, editor and photographer specializing in environmental issues, indigenous rights and sustainable travel.]