Leaders of a March 25-27 convocation on racism made good on an opening promise to accompany participants on a three-day journey to new levels of discomfort and pain.

About 120 participants — women religious and lay associates, nearly all serving as justice promoters or advocates within their congregations — attended the biennial convocation of the Justice Conference of Women Religious in St. Louis. This year, the gathering focused on systemic and institutionalized racism operating invisibly and insidiously, not only in U.S. society and in the Catholic Church, but also, leaders said, in virtually all of the religious congregations that proclaim justice as their mission.

"You are going to experience some uncomfortable 'ouch' moments before we leave here," Sr. Patricia Chappell said in the opening keynote address, which she shared with Sr. Anne-Louise Nadeau.

Chappell is executive director and Nadeau is program director of Pax Christi USA. Chappell is African American; Nadeau is Caucasian. Together, as Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur and as self-described "sistahs," they have struggled as members of an anti-racism team in their own congregation — a difficult and often painful 35-year journey, they said — and have led dozens of anti-racism workshops.

The conference was still in its first hour when Chappell delivered her first major "ouch" as she challenged the familiar words "justice, peace and integrity of creation" many congregations use to describe their contemporary missions.

That euphemistic "one-pot" approach is ineffective because it fails to call out racism, the sin that underlies all the social issues and inequities that religious women are trying to address, she said. "Racism cuts across them all": poverty, violence, housing and education, human trafficking and environmental degradation.

If we are really going to deal with racism, we have to either change the words or recognize that systemic racism is the root cause, Chappell said.

"We use other issues as diversions," Nadeau said. "We'd rather talk about feminism" and the ways we as women are oppressed than look at the ways we are oppressors, she said.

Nadeau said she experienced an "ouch" herself when she looked around the room filled with mostly white faces, tellingly reflecting the makeup of most U.S. religious congregations.

"Why isn't half this room women of color?" she asked. "What did we not do to make women of color feel welcome?"

Participants shared stories about overt racism in their congregations: white sisters refusing to sleep on a mattress a black sister had slept on; unintended hurtful comments; difficulties and conflicts between white employees who work with people of color. But many acknowledged that insidious presumptions of white privilege tend to be unrecognized and unaddressed, even in congregations whose ministries have supported people of color in various ways.

"It's not the big drum roll. It's the little things," Nadeau said in a workshop, "How to Be White Allies." "I suspect racism would drop out of the picture much faster if we were really conscious of our white privilege and what we've gained from that."

Nadeau and Chappell stressed that religious orders need a new set of values, "transformational values" that would effect change in the mindsets that undergird decision-making. Examples of transformational values are inclusiveness, transparency, operating from a sense of abundancy rather than scarcity, and replacing "either-or" choices with more creative approaches.

"We need to allot more resources to justice issues," Chappell said. "The budget will show what a congregation's priorities are."

Nadeau stressed that multiculturalism and "interculturality," values espoused by many women religious orders, are not equivalent to anti-racism.

"We see the openness to welcome sisters from Africa or Asia or Latin America," Chappell said, but sisters of color "who have been here all along" are unimpressed. "It's easier to be in relationship with those from outside, but we think, 'Well, wow. We've been here all along, and you are still not in right relationship with us.' "

Centuries of racism have crippled both whites and non-whites, resulting in internalized racial superiority among white people and internalized racial oppression among people of color, the conference leaders said.

Our history has taught us that as the conquerors, "we are the best, we are the experts. It's part of our psyche as white people," Nadeau said. And when it comes to confronting our racism, "we are very defensive."

Relationships among the races is "a mutual dance" requiring a high level of vulnerability and honesty and courage, she said.

"It's very hard for white people to describe white privilege," said Dominican Sr. Marcelline Koch, who led a breakout session on the topic. "It's like asking a fish to describe the water it's swimming in."

White people in the United States take it for granted that everyone is expected to observe their social norms and that they will get the benefit of the doubt, in contrast to people of color, who often do not, said Koch, a Dominican Sister of Springfield, Illinois.

People of color have a lot of healing of their own to do, Chappell said. In centuries of oppression, of being abused and denied access and resources, including access to religious congregations for many decades, "we have learned to survive," but in the process, "we have done damage to ourselves. It is manifested in never feeling good enough or competent enough. We see it in the violence in [the communities in which we live]. We have to find ways to address that damage and to psychologically heal ourselves."

Sisters at the conference continued to call out "ouches" as a presentation on the history of oppression in the church and society gave new information for many.

One came from the revelation that two papal decrees in the 15th century had lent direct support to both the enslavement of non-Christians and the so-called Doctrine of Discovery. That far-reaching principle of international law declared "discoverers" to be the rightful owners of lands inhabited by non-Christians, justifying western expansion in the United States and centuries of European colonialism.

"That hurts, to see the role of the church in perpetuating racism over the years," said Donna Ewy, an associate of the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Dubuque, Iowa, and a member of the congregation's justice committee. "How easy it is to see myself, as a woman, as the oppressed; how hard it is to see myself as the oppressor."

Others seized on the disclosure that educational benefits of the GI Bill had been denied to African American veterans. The bill, which funded education for millions of returning World War II veterans, was a boon to colleges and universities.

"Our colleges were built on the GI Bill," said Dominican Sr. Brigid Clingman, promoter of justice for the Dominican Sisters of Grand Rapids, Michigan.

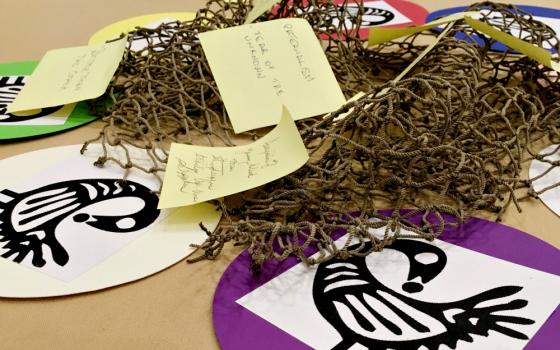

The conference symbol was a mythological bird with its feet planted forward, its head turned to look backward. It represents sankofa, a West African word meaning that the past serves as a guide for the future.

In the closing ceremony, participants wrote on the back of images of the birds their individual commitments to combat racism in their personal lives and in their congregations. They laid them around a fishnet spread out in the middle of each table, symbolizing the web of racism all are caught in.

Participants anointed one another as they read their commitments aloud at their individual tables. They then moved from table to table, arms raised, singing a song of unity, as they read the commitments others had written.

"Your challenge from this convocation is to make the racism piece more prevalent as you do your peace and justice work," Chappell said. "Individually, we have no power. We have to stand together as a collective, drawing on that extraordinary power that comes from within us. We keep going on because we believe that change is possible."

[Pamela Schaeffer is an independent writer and editor in St. Louis.]