Catholic women religious, intent on opening new frontiers for the children of immigrants, laid a foundation of convent schools and academies to educate girls. But when they launched colleges off that base in the 19th and 20th centuries, they helped change the face of American higher education for a new generation.

Like Protestant educators and the founders of religiously unaffiliated colleges, sisters were part of a growing American movement to provide educational equality for women. At the time, colleges were almost exclusively male.

While many Catholic conservatives opposed higher education for women because it might encourage them to seek professional careers or remain single, women religious and some sympathetic male bishops bucked the tide of disapproval, Mary J. Oates wrote in a 1988 essay, "The Development of Catholic Colleges for Women, 1895-1960."

Bishop John Lancaster Spalding of Peoria, Illinois, was one of those sympathizers and a strong supporter of Trinity College for women when it opened in Washington, D.C., in 1900. Oates characterized him this way: "If women seemed to lack capacity for work beyond the domestic, he argued, it was only because men had refused them entry into wider spheres of action. The sphere of woman was 'wherever she could live nobly and do useful work.'"

Now in 21st century America, at a time when faith-based colleges themselves compete for students and dollars, the women religious who stand in the shoes of their innovative and persistent forebears find themselves with an ongoing challenge: how to ensure that they have created a distinctive religious heritage that endures — even when they may not be around to nurture it.

Strategies include governance changes, such as rewriting covenants to make sure that the priorities of the religious community are explicitly part of institutional structure, or by appointing mission officers. But some religious communities also try something a bit less formal, encouraging students to visit retired sisters living nearby, initiating prayer partnerships, or providing ways for them to participate in social justice activities.

Though the tools at hand might be different than those used by their trailblazing sisters, their intent is similar: to change and challenge the culture in which they live, one graduate at a time.

"Women religious would seem to be the likely group to found these colleges. If you go back to the Middle Ages, they were scholars and intellectuals. That interest was present long before they came to America," says Mary Reap, a member of the community of the Immaculate Heart of Mary and president of Elms College, founded by the Sisters of St. Joseph in Chicopee, Massachusetts (with the Springfield diocese and formally called College of Our Lady of the Elms). Reap plans to step down as president at the end of this academic year.

"From the beginning, most of the women who came to us were from first-generation families who wanted them to have a well-rounded education but also to be employed, [though] careers for women were very limited," she says, adding that colleges were a natural outgrowth from the seminaries and academies already in place for Catholic girls.

The story of the women who launched a Catholic education movement in late 1800s and early 1900s America hasn't been told enough, says Michael Galligan-Stierle, president of the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities. If you were to chart a group of leaders before women got the vote or worked in the marketplace, he says, "you would have at the top of that chart women religious . . . they were the first women to have those roles. They led the way."

St. Mother Théodore Guérin, a French immigrant and founder of the Sisters of Providence of St. Mary-of-the-Woods, founded the academy that became Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College in Indiana in 1840, within a year of her arrival. Mary Pauline Kelligar, a Sister of Charity (the order begun by Elizabeth Ann Seton), was the first president of New Jersey's College of Saint Elizabeth, opened in 1899. According to Women in Higher Education: An Encyclopedia by Ana M. Martínez Alemán and Kristen A. Renn, Trinity College in Washington, D.C. (now Trinity Washington University), was the first Catholic women's college not to be preceded by a secondary school. And Notre Dame of Maryland was the first Catholic women's school to award the four-year baccalaureate degree.

As leadership is increasingly transferred to non-consecrated people, the entire community has a responsibility to ensure that the mission, known as the charism, of the founding congregation is carried on in the context of an overarching Catholic identity, says Mary Pat Seurkamp, the retired president of Notre Dame of Maryland University who now works with MPK&D Consulting, a higher education strategy firm.

"Figuring out what those structures and processes are is very much evolving," she says. "Places are experimenting with a number of things. We are learning what works and what doesn't."

ReBecca Koenig Roloff, the 11th president at St. Catherine University in Minneapolis-St. Paul — the largest American Catholic college for women — takes the mission of the founding Sisters of St. Joseph to heart.

"I believe that my job is to make them [the Sisters of St. Joseph] visible in the community, and I want them to be there. Infusing their spirit in the institution . . . requires attention," says Roloff, who last summer became head of the school informally known as St. Kate's. Roloff followed Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary Sister Andrea Lee, now president of Alverno College in Milwaukee.

A thousand miles away, St. Joseph Sister Carol Jean Vale, is approaching her sixth and final term as the president of another order-founded school, originally called Mount Saint Joseph College. Chestnut Hill College, nestled in the picturesque environs of one of Philadelphia's historical neighborhoods, still has a substantial number of sisters on the college staff. "We already have a very robust program. However, we must consider a different approach going forward, because so much of the understanding that our lay colleagues acquired about the charism, spirituality and mission was actually 'caught' through daily interaction with the sisters," Vale says.

Challenging landscape

Catholic colleges founded by women religious have been affected by many of the same trends challenging other schools, including lower graduation rates, student debt, compliance with federal mandates, and the maintenance costs that go with brick-and-mortar institutions. Successful recruitment of students in part depends on having a distinctive identity.

While women religious founded as many as 212 colleges, 80 had closed as of 2002, with eight more legally separated from the Catholic church and another 20 acquired, merged with or incorporated into other institutions, according to Catholic Women's Colleges in America, edited by Tracy Schier and Cynthia Russett.

Currently, 104 colleges and universities founded by religious women remain, according to association statistics. Of these, 24 have religious presidents, including four men.

At the end of the current semester, Indiana's Saint Joseph College will suspend operations for at least the 2017-18 year, Paula Moore, a spokeswoman for the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities says.

Saint Catharine College in Kentucky was shut down in July, and Marian Court College in Massachusetts closed in 2015, Moore says. Moody's Investor Service has predicted that the number of private college closures will increase over past levels.

Gone are the days when women religious were the primary staff on the campuses they had started. Lay involvement started to climb during the 1960s, with boards taking over the supervisory responsibilities that were once the sole province of sisters, according to Schier and Russett's book.

Sisters and lay leaders on many of these campuses say that this trend has been going on not for years, but for decades. The first non-consecrated person in charge of a sister-founded school, for example, was Dr. George Hermann Derry, who became president at Marygrove College in 1927.

Yet, sisters are very much in evidence on college and university boards, showing a keen interest in defining and shaping the way their charism (specific mission and spirituality) is passed on to future generations.

As executive director of the Association of Colleges of the Sisters of St. Joseph, Martha Malinski works with nine member schools. Only one of them, Philadelphia's Chestnut Hill College, has a sister at the helm.

"Transition and change are always very difficult and emotional, especially when we're talking about people, communities, and how they continue to live on," says Malinski. "I think it's very challenging."

Part of her job includes planning events that bring together key personnel, from vice presidents to campus ministers, to plan collaborative activities, she says. This year, a grant from National Catholic Sisters Week will enable campuses around the country to hold a social-justice-themed event focused on the Sisters of St. Joseph mandate to care for the "dear neighbor."

Continuing the charism

Jean Wincek, a Sister of St. Joseph of Carondelet, St. Paul Province, serves as vice chair of the board at St. Catherine University. About eight years ago, she says, the school launched a new governance model, creating a sponsorship council to oversee both possible changes to mission and the nitty-gritty of bylaw revisions, property transactions and potential mergers or closings.

"We wrote a document called a covenant to inspire and guide the board of trustees about how we work together. That core relationship is what helps to shape the university's future," she says. The school has three mission directors to oversee that the three fundamentals — Catholic, women and liberal arts — are woven through the fabric of the school. Seven sisters out of 30 sit on the board of trustees.

But the sponsorship council and the local sisters didn't stop there. They also focused on concrete ways to further link sisters with students. Sisters signed up to be prayer partners. Each fall, the sisters host a picnic and a tour for new students. At the beginning and end of their college careers, students take a course intended to strengthen the commitment to Catholic teaching on social justice so crucial to the mission of the Saint Joseph of Carondelet sisters.

"We have huge community involvement with all of our students," says Roloff, pointing out that St. Catherine University has a Center for Community Work & Learning. "I believe that the role of the women's college, and, even more so, a Catholic women's college, has never been more important than right at this moment," she says.

While in 1905 the school welcomed immigrant daughters from the prairie, this year the freshman class will include 44 percent women of color, she says proudly. "The charism of being a Catholic, liberal arts and women's institution guided us for the first hundred years, and [continues] to carry us into our second."

On the cusp of graduation, senior Shannon McKeever, student senate president, echoes the president's enthusiasm as she says that she was drawn to the school by its focus on equipping women for leadership through education. McKeever, who hopes to work for a nonprofit when she graduates, acted purposefully to connect with the sisters through her work on human trafficking.

"You definitely have to be intentional to make those connections, because they aren't as visibly present anymore," she says, though she notes that students can volunteer at the sisters' nearby retirement community, Carondelet Village.

"The sisters made a point when they founded the school that it wasn't a finishing school but a college. That's been very present throughout its entire history but it's especially current," says McKeever. "Students are expected to develop their leadership potential in the classroom, on and off the campus."

The tradition of hospitality practiced by the Sisters of St. Joseph also permeates the campus, she adds. In the campus ministry department, Muslim students, a large population on campus, have a place of their own to worship. "It's here and we know it's here," McKeever says of the order's presence.

In New Haven, Connecticut, interim president Sr. Anne Kilbride and Sr. Joan Scanlon, interim special assistant to the president for Dominican Mission, are working with an advisory board to make sure that the mission of Albertus Magnus College doesn't rely on the presence of religious sisters on campus.

When there were more sisters on the grounds, the Dominican mission of the founders (promoting the search for truth in all its dimensions) "just walked with you and permeated you. But as the number of sisters grew smaller, there was a need to articulate it more, and to empower laypeople to carry that Catholic identity forward," says Kilbride.

"I don't look at it as a relinquishing," she adds, listing the numerous ways, including book studies, banners, a founder's day celebration, and various social service programs, that the message is echoed inside the classroom and on the campus, which became coeducational in 1985*. "I think our role as religious is to promote and to spread this charism, this identity, this mission."

"Sister Anne has created a program here that is sustainable and replicable," Scanlon says. "I feel blessed to have the opportunity to pass the charism on to students and faculty."

She chuckles at a comment another school staff member made to her recently about the college's lure for students: "They aren't too high on being Catholic, but they love being Dominican."

The fifth lay president of Marian University in Indianapolis, Dan Elsener, is going into his 16th year at the helm. Elsener says his university has worked hard to ensure that the mission of the Sisters of St. Francis of Oldenburg, Indiana, who founded the school (originally Marian College), is integrated consistently throughout the school, including the details of the handbooks and the constitution.

Though the sisters have been working with lay presidents for decades, he says, in some ways, "we're probably living out the mission more strategically and intentionally than we did in the past."

Simply put, says Elsener, "We don't want to disappoint them. Plus, it makes our university rich, distinctive, makes a much more powerful experience to be there because the spirit — of the Catholic and Franciscan tradition and Franciscan charism — imbues everything we do."

What lies ahead

At Chestnut Hill College, there are 41 Sisters of St. Joseph on the faculty, says Vale — an extraordinarily high number for any American Catholic college or university. But she is acutely aware of the need to prepare for a future that may look quite different. "In all too short a time, we won't be around in large numbers to witness to the essence of what it means to be a Sister of Saint Joseph, so it is imperative that we develop a plan to provide both experiential and theoretical education," she says.

At Chestnut Hill, those plans include an associates program that educates faculty, staff and administrators about the charism, mission history and spirituality of the Sisters of St. Joseph, as well as other lay formation programs. Students can participate in the 1650 Society (the date the order was founded), learning about the Sisters of St. Joseph and participating in service to the "dear neighbor."

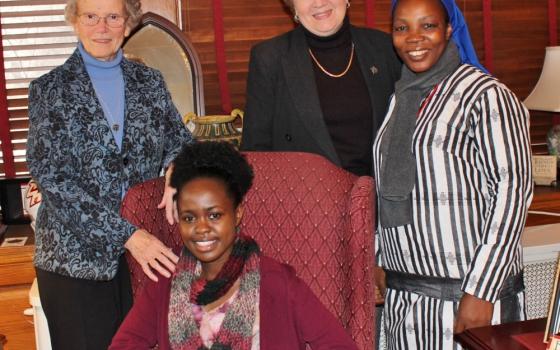

First-year orientation, periodic retreats, residential life experiences and even specially crafted cards adorned with the sayings of the congregation's founder Jesuit Fr. Jean Pierre Medaille written in contemporary English offer students multiple chances to experience the values of the order — as do service trips to Camden, New Jersey, the Appalachia region and Tanzania, says Vale. And that's just the beginning of the multi-dimensional, 360-degree approach taken by the school.

Though religious women educators don't have to grapple with the physical challenges of prairie life or the anti-Catholic bias many of their predecessors faced, today's challenges are real enough, if more abstract.

The women interviewed for this story seemed more resolute than intimidated, though.

"Many of us are working to right-size our institutions," says Vale. "We simply cannot continue to do what we have always done."

But it falls to one of them to say what is increasingly obvious — that the pioneering women religious who helped shape the American educational landscape are disappearing and no longer setting the course of the institutions they were responsible for creating.

Noting that she is the only Sister of St. Joseph left heading one of the order's colleges and universities,Vale says: "This fact is indicative of the present time and foreshadows the time when none of the presidents will be Sisters of Saint Joseph. I feel the deep and costly loss of a treasured and trusted presence in Catholic higher education."

Now and then, says Vale, a convert herself, she takes a moment to distance herself and "consider those extraordinary women who have been quiet giants among us as they fearlessly built huge institutions to serve the people of God. I am in awe of these women . . . long before feminism, they witnessed the way forward for women. I am humbled," she concludes, "and blessed to walk in their footsteps."

*An earlier version of this story gave the incorrect year.

[Elizabeth Eisenstadt Evans is a religion columnist for Lancaster Newspapers, Inc., and a freelance writer.]