Richard is 6 years old and has cerebral palsy. His legs can’t support his upper body, so he uses a walker and braces on his legs. His equipment looks like it’s from the last century: leather straps with big buckles for his leg braces, clunky black orthopedic shoes, a walker made from welded metal and painted green to make it less industrial.

But all of Richard’s equipment was specially created for him on site at a workshop at the Naromoru Disabled Children’s Home. And it cost less than $200.

“We’ll help a patient more by doing it locally,” explained Emma Muthanje, a 25-year-old orthopedic technologist, who creates and designs prosthetics and braces for patients at the children’s home.

Muthanje, who studied orthopedic technology at the Kenya Medical Training College, looks at each patient as a puzzle: What part of the body needs extra support? What kind of brace will someone use, if their prosthetic is built like this? What if there is a temporary splint after an operation? Everything she builds is customized to the person who will use it. And children grow, sometimes quickly, requiring new prosthetics, splints and braces.

“The prosthesis must be custom made, because every person has his or her own measurement,” said Muthanje. “You have to work individually with every person that comes.”

Importing this equipment from Europe or America would entail major delays. Shipping costs alone would be higher than the cost of building it locally, not to mention delays or lost shipments, or the headache of returning broken equipment, and having a child wait months for delivery.

“[Building here] is much cheaper than importing these things,” explained Muthanje. “Just a prosthetic foot [from abroad] costs $100, plus the shipping it can easily be $150. When we create a below-the-knee prosthetic it costs $80 to $120, if it’s between the knee and the hip, it costs between $120 to $200. If we imported a prosthetic like this, the cheapest possible would be $500 but more likely around $2,000.”

She added that even when non-profit organizations try to bring parts of the prosthetics from abroad, they run into issues during periods of unrest, like the post-election violence in 2007-2008. When riots paralyzed the country, they also stranded people who were waiting for braces or prosthetics.

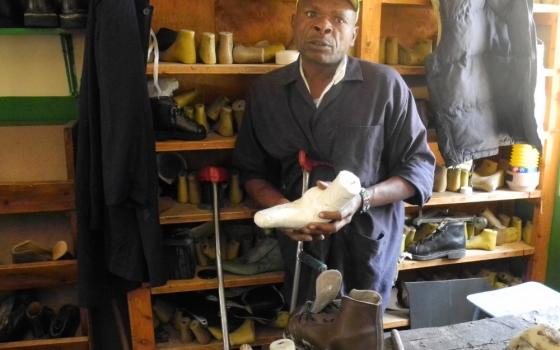

Pius Gichunge was a patient in the 1990s at the Naromoru Disabled Children’s Home for his club foot. For the past 15 years, he has designed orthopedic shoes for hundreds of patients. The shoes may not win accolades on the runway for style, but they work. He builds each shoe from a mold of the child, and it costs less than $15.

A metalworker, Jackson Njuguna, makes walkers that he customizes for each child, or for adults who come as outpatients. He also creates braces to help train children to sit up properly if they don’t have inner body strength. Njuguna works with the physical therapist on site to take measurements; he can build the walker within three days.

It takes Muthanje and co-worker Moses Sifuna approximately a week to make a lower-limb prosthetic. They use resin and polypropylene in a special oven brought from Italy. The feet are made from scratch from a block of wood.

“I always knew I wanted to do this,” said Muthanje, who is from Thika, a city on the outskirts of Nairobi. “I saw so many people in the streets of my hometown with muscle deformations and amputations, and I wanted to do something to help.”

“In the northern part of the country, most of the people with prosthetics got them from here, because there’s no other factory north of here,” she added. “When you see someone using your prosthetic, it is so fulfilling. There’s nothing else you wish to do in life.”

[Melanie Lidman is Middle East and Africa correspondent for Global Sisters Report based in Israel.]

Related - 'Show them they have special abilities' by Melanie Lidman