Throughout his divisive presidential campaign, President Donald Trump promised legislation that would crack down on immigrants living in the United States illegally. Since his inauguration, he has been making good on those promises.

In a January 25 executive order, he threatened to pull federal money from any "sanctuary jurisdiction," which the order defines as any federal, state or local law, person or agency that places restrictions on Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

It didn't take long for large cities such as Chicago, Los Angeles and New York to react to the order, declare themselves sanctuary cities, and fight against it in the courts.

Since then, more states, cities, churches and faith communities have declared themselves "sanctuaries" — a broad term with no clear definition. Generally, the term indicates an unwillingness to have local law enforcement cooperate with ICE officials. But the term itself has no official legal bearing, and definitions can differ.

According to The New York Times, at least five states and 633 counties already have laws that limit the interaction between local police and ICE. Yet only 363 counties have declared themselves a sanctuary jurisdiction.

While governments and other faith communities have publicly affirmed their assistance to immigrants without legal permission to be in the United States, the Catholic response has been quiet.

Most sister communities, when asked, said they do not have a statement at this time. Many communities told GSR they are still discerning what the appropriate next steps are for their communities.

Srs. Anna Marie Broxterman and Judy Stephens, Sisters of St. Joseph of Concordia, Kansas, were part of the sanctuary movement in the 1980s, when migrants fled to the United States to escape violence in Central America. They said their faith lends itself to the idea of sanctuary.

However, Broxterman said, "Right now, the listening process hasn't led us to declaring public sanctuary."

Although her community has yet to make a decision about sanctuary, Stephens said they are using Catholic social teaching and Pope Francis as their guides.

"We have a strong background within our Catholic faith of doing [sanctuary]," Stephens said.

Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago recently wrote in a letter to priests in the archdiocese that the archdiocese would not participate in the sanctuary movement.

"We have not named our churches as 'sanctuaries' solely because it would be irresponsible to create false hope that we can protect people from law-enforcement actions, however unjust or inhumane we may view them to be," Cupich wrote.

Cupich did note that should ICE officials approach priests in order to come onto church premises, priests are to ask for a warrant and to consult with the archdiocese's legal counsel.

Refugees in the Reagan years

Sanctuary "has almost always been intertwined with communities of faith," said Grace Yukich, an associate professor of sociology at Quinnipiac University in Hamden, Connecticut. "Most people trace at least the practice of sanctuary in the West to certain passages in the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament that establish cities of refuge."

The modern sanctuary movement in the United States was born in the 1980s from unrest in Central America.

During that time, civil wars erupted in El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua. Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero was assassinated in 1980 after denouncing the killing of civilians. Later that year, members of the El Salvador National Guard raped and murdered Maryknoll Srs. Maura Clarke and Ita Ford, Ursuline Sr. Dorothy Kazel, and lay missionary Jean Donovan.

According to the Migration Policy Institute, between 1981 and 1990, almost 1 million Salvadorans and Guatemalans fled civil wars and death squads and headed for the U.S.-Mexico border.

Hostile refugee policies awaited them there.

The Migration Policy Institute reports that the administration of President Ronald Reagan refused to acknowledge the human rights violations occurring in the migrants' countries of origin. Instead, refugees were categorized as "economic migrants," making it difficult for them to apply for political asylum. In 1984, less than 3 percent of asylum cases from El Salvador and Guatemala were approved.

The treatment of the refugees at the border spurred Jim Corbett, a Quaker, to take action. Corbett asked the Rev. John Fife of Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson, Arizona, to assist detained refugees, according to Scott Wright in Standing on Holy Ground: Responding to the Call for Sanctuary.

Wright, director of the Columban Center for Advocacy and Outreach, writes that not long after, Fife officially declared his church a sanctuary for refugees. Both Fife and Corbett were active in the creation of the underground railroad that brought refugees from the border to various U.S. states or to Canada.

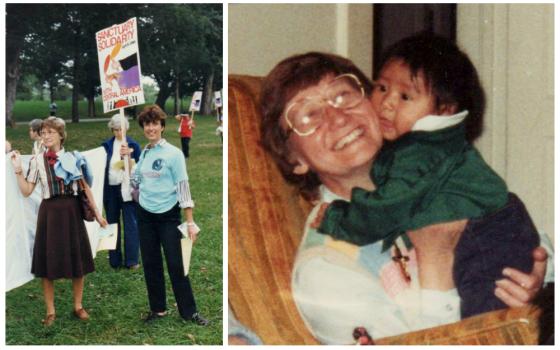

Sisters played a part in every step of the sanctuary movement — assisting refugees across the border, securing a place for them to stay, and offering rest along the underground railroad, all at the risk of jail time.

Notre Dame de Namur Sr. Nancy Wellmeier, who worked closely with Corbett and Fife during the 1980s, became involved with the movement after she visited Guatemala and saw the "genocidal warfare" refugees were subjected to.

This experience prompted her to join the Valley Religious Task Force on Central America, a Phoenix-based interfaith group founded in 1981 to aid and advocate for Central American refugees. Wellmeier worked part-time as a sanctuary counselor at the task force's safe house for refugees in the Phoenix area.

Once refugees arrived at the safe house, Wellmeier listened to each story and discussed with them their options: travel the sanctuary movement's underground railroad to Canada, or be connected with an asylum lawyer in the United States.

Broxterman got her start in the movement after a written invitation from a community of nearby Mennonites in the winter of 1983. At the time, she was the director of Manna House of Prayer, a retreat center in Concordia, Kansas.

Although the Mennonites did not formally get involved with the sanctuary movement, they were aware of the work Fife was doing in Phoenix and of the mission of the Sisters of St. Joseph.

The Mennonites "had heard of us because one thing we had said in our mission statement at Manna House was that we would have our house and home open to those in need, and we didn't define the need," Broxterman said. "So the Mennonites were aware of the differing social issues we got involved with because of that statement and our mission statement, and so they wrote to ask us if we would consider becoming a sanctuary for Central American refugees."

After a period of discernment, members of the Manna House of Prayer publicly declared it a sanctuary and received their first family April 23, 1983.

"You have to have the humility to go public," said Stephens, who worked with Broxterman at Manna House of Prayer during the 1980s. The hope was that, by going public, what was then the Immigration and Naturalization Service would avoid raiding the property because of the negative publicity it would draw, she added.

"It seemed strange, on the one hand, to be so public, but it was our protection," Stephens said.

By 1987, Broxterman, Stephens and Wellmeier saw their numbers of refugees and work begin to dwindle after the signing of the Central American peace accords. The accords, which were signed by Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica, gave amnesty to political exiles and called for the return of refugees.

In 1990, U.S. Congress also passed legislation allowing the president to designate "temporary protected status," which led the way for refugees from Central America to gain permanent status.

"The Valley Religious Task Force stayed kind of in connection with each other, but after the signing of the peace accords in the early '90s in the Central American countries, we didn't see the same phenomenon of people escaping that kind of violence," Wellmeier said.

A different national context

Despite the lull in refugees escaping from Central America, faith communities never stopped being part of the movement.

"Even though the national movement and the press coverage of the national movement died down eventually, the churches never stopped offering sanctuary," Yukich said.

The sanctuary movement began to garner national attention again when officials, in response to an increase of immigrants entering the United States illegally, proposed bills targeting the immigrants and those who helped them in the mid-2000s, Yukich said. As a result of the bills not passing and comprehensive immigration reform failing, the sanctuary movement had lost steam by 2009, Yukich said.

However, this history laid the groundwork for what's happening today, she added.

"Because people had already organized, because leaders had already emerged and because many of those people have continued doing at least some work since that time, it made it much easier to get things going, now that there's a much more pressing perceived threat for immigrant communities," Yukich said.

Stephens and Wellmeier are among those who continued the work after the Valley Religious Task Force disbanded in 1998.

Stephens worked with Catholic Charities in Salina, Kansas, as a Spanish medical interpreter from 1998 to 2008. She has also helped coordinate trips to the U.S.-Mexico border that serve as both volunteer and educational experiences.

Wellmeier and Notre Dame de Namur Sr. Maria Olivia Pacheco created their own ministry, Centro de Educación Santa Julia, in Mesa, Arizona. The center opened in October 2009 and provides English-as-a-second-language and citizenship classes, as well as assistance with document translations.

And while Stephens and Wellmeier continue their work with communities of those in the country illegally, they said it is hard to figure out how best to serve immigrants under the Trump administration.

"With this new crisis, we have offered to help people with power of attorney so they can designate someone to take care of their children if they are deported or designate someone to manage their property, bank account, house, car, whatever," Wellmeier said, adding that there might even be a need to figure out who will take in children whose parents have been deported.

Wellmeier is also letting her English-language students know that "if they fear being deported imminently, they can stay [at the center]. All they have to do is call."

She does, however, stop short of calling it a "sanctuary."

"We hesitate to use the word. Not that there's anything wrong with it, but it just attracts trouble," Wellmeier said, referring to the added attention when declaring sanctuary. "You can do the action without using the word, is how I feel. There is no legal definition, and basically unless you do it, it's meaningless to say it."

While women religious and Catholic churches did sign on to the sanctuary movement in the 1980s, many are quick to point out that the climate surrounding immigration has changed since then.

"There were just procedures [back then] that people could follow and expect some kind of justice," Wellmeier said. "People were entitled to a hearing in front of an immigration judge, and they had been up until now, but people are being deported without a hearing."

"It seems that those people who really want everybody gone have permission now to do it," she added. "And how those who think otherwise can fight against it, I'm not sure."

Yukich said the publicity garnered from declaring sanctuary may no longer mean protection from immigration officials.

"INS in the '80s was a very different organization compared with ICE, and the national context now is different than it was then," Yukich said. "We don't know what Trump is going to be like as a leader. We don't know [what Attorney General] Jeff Sessions is going to do as a leader. It's a little early to say who will and won't be prosecuted for doing something like sanctuary."

Those working in the sanctuary movement recommend that organizations look into other ways to provide accompaniment to immigrants rather than just physical sanctuary.

"We've been expanding its definition. When we launched back in 2007 ... we thought about the word as a way to open up the dialogue," said the Rev. Juan Carlos Ruiz, a Lutheran minister and a part-time organizer with the New Sanctuary Coalition in New York City. "The word is a way to kind of unleash our imaginations about our sacred spaces ... and that these sacred spaces are not just physical."

The New Sanctuary Coalition involves more than just space for undocumented immigrants to stay, Ruiz said. The movement accompanies people through immigration proceedings and provides legal help and education for the community.

All of this weighs on women religious communities.

"I don't know if it's a climate of the nation right now, but it just seems like there is an urgency, and yet the clarity about what could be done isn't coming as clearly as the urgency is coming," Broxterman said. "So that's a kind of conundrum within me. Why does it feel so urgent and yet I don't know what it is? Anything that we choose to do seems so small in light of the urgency."

[Kristen Whitney Daniels in an NCR Bertelsen editorial intern. Her email address is kdaniels@ncronline.org.]

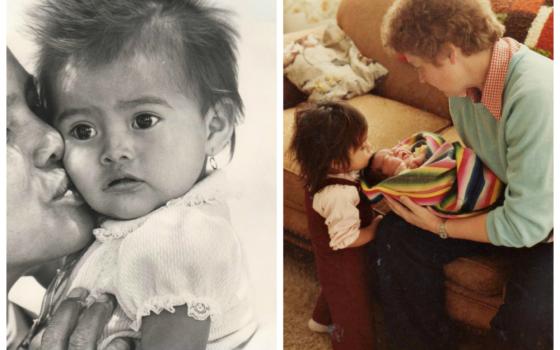

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story misidentified the child in the first and last photo.