Editor's note: More than 68 million people had been displaced from their homes because of factors such as war, threats from gangs, natural disasters, and lack of economic opportunities at the end of 2017, the highest number of displaced since the aftermath of World War II. Of those, the United Nations considered 25.4 million to be refugees: people forced to leave their countries because of persecution, war or violence.

Global Sisters Report is bringing a sharper focus to the plight of refugees through a special series, Seeking Refuge, which will follow the journeys refugees make: living in camps, seeking asylum, experiencing resettlement and integration, and, for some, being deported to a country they may only vaguely remember or that may still be dangerous.

Though not every refugee follows this exact pattern, these stages in the journey are emblematic for many — and at every stage, Catholic women religious are doing what they can to help.

______

Some days, Angelika Ouma isn't even sure what side of the border she's on. "I was born in Sudan, then I came here [to Uganda] when the situation was bad, then I went back to Sudan when it was bad in Uganda, and now I'm back here," said the nursery school teacher, 73.

Over 60 years, Ouma's career has crisscrossed the border in pursuit of a peaceful place to teach children: She completed primary school in Uganda but returned to Sudan for higher education. Fleeing violence in Sudan, she first worked as a nursery school teacher in Uganda, where she met her husband. Together, they fled to South Sudan when northern Uganda was unsafe. Ouma finished her career and retired, expecting to relax in South Sudan. But, suddenly, after fighting broke out in her village, she found herself, now widowed, once again fleeing across the border.

Now, along with the Missionary Sisters of Mary Mother of the Church, she helps coordinate emergency nursery school classes for more than 70 South Sudanese refugees from her community in Kocoa village in northern Uganda. Refugees make up about a quarter of the students at the Bishop Caesar Asili Memorial Nursery and Primary School.

In addition, a small percentage of South Sudanese refugees who were able to secure scholarships at schools outside the settlements have been absorbed into regular classes with Ugandans. Read about the Missionary Sisters' work at a girls secondary school in Adjumani.

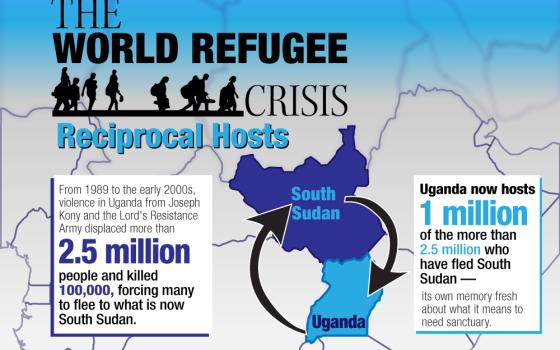

As countries around the world grapple with the wave of refugees flooding their borders, Uganda has quietly accepted a million South Sudanese refugees, almost half of the more than 2.5 million people who have fled South Sudan since 2014, according to the United Nations High Commission on Refugees. Today, the country absorbs an average of 500 refugees from South Sudan per week, which is considered a quiet period. At some points, 1,000 children were fleeing South Sudan every day.

This has made Uganda, in the course of just a few years, the country in Africa with the largest refugee population and one of the top five host nations around the world.

The country also hosts almost a quarter of a million refugees from the Democratic Republic of Congo and over 70,000 refugees from Burundi and Somalia, according to 2017 U.N. data.

Although there are significant challenges, and many refugees living in settlements complain of issues with security and sanitation, Uganda's attitude toward refugees is considered more liberal and accepting than many other countries.

Uganda has "one of the most open refugee policies in Africa, and most likely in the world," U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi told reporters after visiting the Imvepi Refugee Settlement in Uganda in January.

Part of that is because the memory of being a refugee is still fresh for many northern Ugandans, where the majority of settlements are located.

Starting in 1989, Joseph Kony, a self-described prophet bent on overthrowing Uganda's longtime president, Yoweri Museveni, instructed his followers to kidnap children as young as 8, brainwash them and force them to burn down homes and rape and kill their neighbors. The violence displaced more than 2.5 million people in northern Uganda and left 100,000 people dead. Kony and his guerrilla group kidnapped more than 30,000 children, both boys and girls, and forced them to commit atrocities during two decades of war.

The Lord's Resistance Army eventually crumbled into disarray and the war petered to a halt in the 2000s. Despite international attempts to capture Kony, he fled to Sudan or the Central African Republic with a small group of supporters and is still at large.

Northern Uganda began to emerge from the years of terror. Those who had fled their villages — many to the part of Sudan that is now South Sudan after it gained independence in 2011 — returned. Religious leaders oversaw traditional forgiveness ceremonies to try to heal the communities' wounds. Sisters and educators created special training and educational opportunities for returning child soldiers to help them integrate. With time, these traumatized children became community leaders and advocates for peace.

Farmers planted crops in land that had previously been abandoned. Gulu, the regional capital, started growing at a breakneck speed, with a network of newly paved roads linking it to other cities in the region.

Then civil war broke out in South Sudan in December 2013. Before long, hundreds of thousands of South Sudanese began to flee across the border to Uganda's relative stability.

"There's a culture here in Uganda of welcoming," explained Sr. Helen Tabea, a member of the Evangelizing Sisters of Mary from Uganda, and an English teacher and program coordinator with the Jesuit Refugee Service in Uganda. "And the fact that Ugandans have experienced difficult times for a long time, we remember what it's like. The South Sudanese and the northern Ugandans are basically cousins. They speak the same language."

Jesuit Fr. Kevin White, the country director of the refugee service, says Uganda has an excellent refugee law today "and it's because they have a live memory of when they themselves were refugees."

The government of Uganda is careful to refer to refugee "settlements," not "camps." Every few months, they build a new settlement, which quickly fills to capacity. Bidi Bidi, now considered the world's largest refugee settlement, on par with Kenya's Dadaab camp, with almost 250,000 people, opened in August 2016 and was filled by December.

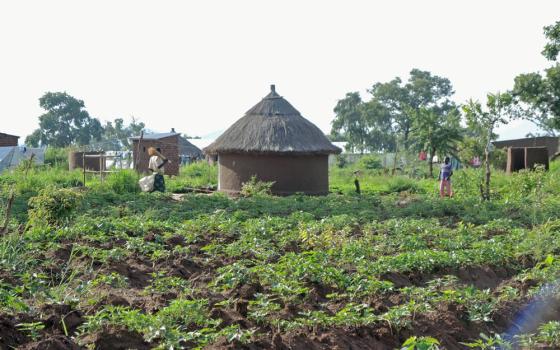

Refugees in Uganda can move freely about the country and obtain work permits. Most are assigned a 30-meter-by-30-meter (1076-square-yard) plot of land in a settlement, where they are encouraged to build their own homes, dig a pit latrine, and grow some of their own food, in an effort to encourage self-sufficiency and promote dignity. It also fights a common side effect of refugee camps in rural places around the world: soaring inflation for the local population when refugees are given cash by international nongovernmental organizations.

"The humanitarian response about Uganda has been quiet because Uganda is doing a good job," said White. "You only get attention when it bleeds."

He gave the example of a summer 2016 cholera outbreak that was dealt with effectively. "The irony is that, if it wasn't contained, we would have gotten headlines and maybe more money."

Although Uganda's policies are better than those in most surrounding countries, the situation isn't tenable, White noted.

In some parts of northern Uganda, refugees will soon outnumber nationals, as Uganda is on track to absorb an additional 400,000 refugees during 2018. In 2016, the region of Adjumani had 170,000 refugees and 210,000 Ugandan nationals. Land is quickly running out, and refugees who come these days may only receive a 10-meter-by-10-meter plot of land, which will not be enough to grow their own food.

There is not enough water in the area to support such a large population, and trucking in water has become prohibitively expensive. Trees are disappearing as a growing population cuts them for firewood.

For now, the Ugandans have been welcoming their neighbors to the north, but as competition for resources increases, this goodwill may disappear.

Tabea said the plots that encourage refugees to cultivate their own food are essential to maintaining good relations between the refugees and the local population. "[Refugees] must stand up on their own, and people do," she said. "People start working, or they sell small items. Uganda doesn't have a lot of resources but we do have very rich soil. Within two weeks you can have vegetables and within a month you can have beans if the rains cooperate."

'We've always had wars around here'

Sisters in northern Uganda have had to quickly adapt their ministries for a changing population, especially those working in education.

Yet, despite the severity of the South Sudan refuge problem, the changes at individual schools and ministries were not very drastic. Many of the sisters were already working with Ugandan refugees who were starting to return, so were familiar with the traumas refugees face.

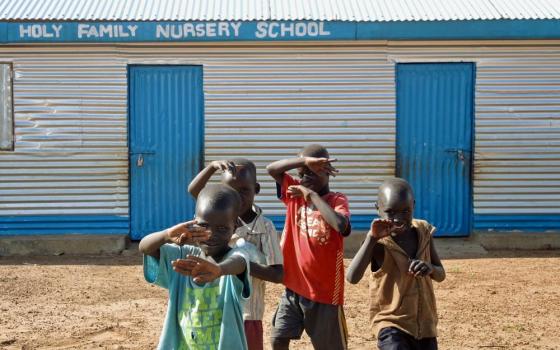

If the walls could talk at the new Bishop Caesar Asili Memorial Nursery and Primary School, they would tell the history of a fractured region. The building was originally constructed as a novitiate for the Missionary Sisters of Mary Mother of the Church congregation, but in 1992 rebels from the Lord's Resistance Army broke into the compound, killed a watchman and kidnapped a sister, who was later rescued. The congregation left the area and moved south to safer parts of Uganda. Sudanese seminarians from the Comboni congregation moved in, but then went back to South Sudan.

The sisters began returning to the area over the last decade, first re-establishing a health center and maternity lab. The school opened in early 2017 as a nursery and primary school. Refugees make up about a quarter of the enrollment.

"The refugee children have a different character from the children here, they have wild behavior because they are traumatized," said Sr. Laura Kaneyo, the head teacher.

She said the children are often fighting. "They were born in the war, they grew up in the war, they don't know peace," she said. "Without a big heart you cannot handle this group of people, you must have patience and tolerance."

Kaneyo depends on people like Angelika Ouma, the kindergarten teacher who was a pillar of her community in Nimule, South Sudan. When Ouma fled to Uganda in the current round of fighting, many families followed her to Adjumani so they could enroll in her school again.

Ouma is part of the South Sudanese Madi tribe, and her husband, now deceased, was a Ugandan Madi. The fact that the tribal identity straddles the border has made the transitions logistically easier, though still emotionally wrenching.

She looks out over her charges, a dozen rambunctious boys of varying ages who are at the school, even though it is vacation time, because there is nothing to do at the settlement. They gather to sing traditional Madi songs for a guest and then help the school's "mama" cook lunch.

Sitting in a plastic chair, she watches as workers put the finishing touches on an expansion to the school, which will allow them to open another classroom and serve more children, both Ugandan and South Sudanese.

She doesn't know which side of the border she will end up on, or if she will be alive to see peace. Like many South Sudanese refugees, she longs for a day when she can return "home," to South Sudan, even though she has spent more than half of her life in Uganda. But she also knows how to provide stability for her main concern, the children under her care, despite the question mark that is their future.

"Since 1955, we've always had wars around here," said Ouma. "From the time I was 10 until now, we've always been at war."

[Melanie Lidman is Middle East and Africa correspondent for Global Sisters Report based in Israel.]

Next in this series: Jordan historically welcomes waves of refugees but would prefer them not to stay so long.