Sr. Maria Gaczol and Sr. Veera Bara close the gate outside their hillside apartment tucked in an alley on a main street of Agrigento, a town of about 60,000 people on the southwestern coast of Sicily. Two elderly Sicilian men greet the sisters as they pass.

"Buongiorno, sorelle," they say in Italian, or, "Good morning, sisters."

Gaczol and Bara respond in their best Italian accents.

"Buongiorno," they say with a smile.

They continue down the narrow road in a town they've called home since December, forming a single-file line on the sidewalk to avoid getting brushed by a passing car.

"Now they recognize us," Bara says in English, describing the locals.

It's 11:30 a.m. on a Wednesday, but the streets are mostly empty. Many of the townspeople are seeking shelter inside to escape the July heat.

"There aren't any [migrants] out today," says Gaczol, a Polish native and member of the Society of Sacred Heart. "The lunch hour isn't the best time. You can usually find them out on the street."

Almost every mid-morning, the sisters head to the local mensa — soup kitchen — to visit with African migrants living in Agrigento.

"Being with these people gives me a real picture, I think more than what I read on the internet or in the newspaper, of the personal story and the sufferings they have gone through in their own country," says Bara, a Sister of Mercy of the Holy Cross from India.

Gaczol, Bara and nine other sisters make up the Migrant Project/Sicily, a program founded by the International Union Superiors General (UISG) in Rome to aid migrants in Sicily by developing one-on-one relationships with them and helping them assimilate to their new home. The sisters are responding to a migrant crisis that has gripped the world through news headlines and images of bodies cascading out of rubber dinghies in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea. Some are escaping violence in their home countries; others seek relief from political unrest.

The project, based in Agrigento and Ramacca in Sicily, took shape after two women religious asked leaders at UISG how their communities, the Comboni Missionaries and the Missionary Sister Servants of the Holy Spirit, could respond to the crisis. The executive board at UISG also wanted to contribute, so the board decided to mark its 50th anniversary with the migrant project.

The influx of migrants from sub-Saharan Africa has rocked the very core of the Italian island and Europe, leaving politicians, European Union member states and citizens with conflicting views on how to address the crisis.

According to a recent Pew Research Center report, around 90,000 people have come to Italy from Africa since January. Sicily, already strapped with its own economic worries, has yet to find a solution to the migration problem.

"I think politicians are almost unable to know where to begin to solve this," says Sr. Patricia Murray of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary, executive director of UISG. "This is an unprecedented movement of people in such numbers in such a short period of time."

The Central Mediterranean route is the main gateway from sub-Saharan Africa to Sicily, according to Frontex, a European border agency based in Warsaw, Poland. Migration from Africa to Sicily increased 287 percent between 2008 and 2015, from 39,800 migrants to almost 154,000 migrants. Eritreans, Nigerians and Somalis made up the biggest portion in 2015.

According to the U.N. Refugee Agency, more than 1 million migrants arrived in 2015 by sea to Europe — 153,600 of whom landed on the shores of Italy.

Migrants generally travel from their home countries to Libya, where they pay smugglers for a passage by boat to Italy. But the journey is often treacherous.

"Smugglers typically put migrants aboard old, unseaworthy fishing boats, or even small rubber dinghies, which are much overloaded and thus prone to capsizing," the Frontex site states. "For these reasons, the vast majority of border control operations in the Central Mediterranean turn into Search and Rescue (SAR) operations."

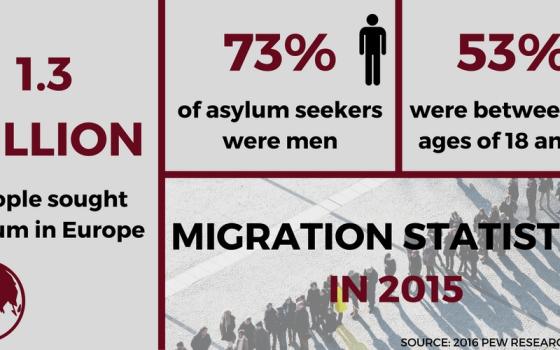

A record 1.3 million people sought asylum in Europe in 2015, the greatest influx to the continent since 1985 and the largest in almost 25 years, according to a Pew report released Aug. 2. Almost three-fourths — 73 percent — of the continent's asylum-seekers in 2015 were men, and more than half were between the ages of 18 and 34.

Migrant Project/Sicily, overseen by UISG's Sr. Elisabetta Flick of the Religiosa delle Ausiliatrici del Purgatorio (Helpers of the Holy Souls), took one year to plan, including scouting for the sisters who would take part, interviewing candidates, and choosing the locations in Sicily. Two bishops, Cardinal Francesco Montenegro of the Agrigento archdiocese and Bishop Calogero Peri of the Caltagirone archdiocese, were key components in choosing the sites, Flick says.

In 2014, Montenegro invited Flick to Sicily to gauge the situation.

"He didn't want a fixed structure," Flick says of Montenegro's request. "He wanted sisters to meet migrants in the streets."

The project's focus — to be nella strada, or "in the street" — connects with Pope Francis' call to work in the peripheries, Murray says. Forming relationships with locals, both religious and nonreligious, is essential to the project's success, she adds.

Montenegro "didn't want us to come with a set project. He wanted us to come and keep our eyes, our ears and our hearts open and to see where we were led," Murray says.

Scene from a soup kitchen

Rigid schedules are obsolete to the sisters. They go where help is needed, like mensa — run by a local missionary group — hospitals and, in the fall, prisons in Ramacca.

On this particular morning walk to mensa, Gaczol and Bara stop at the town square to chat with a group of migrants they encounter. There, a Moroccan in his mid- to late 40s sits on a stoop with a tray full of lighters in his lap. Two young African men sit beside him. The Moroccan, who arrived in France in 2014 then made his way to Sicily on a Pullman, said he makes about 5 Euros a day selling lighters (about US $6.60).

"One day [here] is like passing 100 years," he says in Italian.

A Senegalese man in his mid-20s chimes in.

"I would go home tomorrow if I could," he says. "I can't work here. I can't do anything."

He was a mechanic back home, he explains in Italian, but he's unable to work in Italy because he's waiting for his asylum papers to process. It's been a year and a half since he arrived in Sicily.

The Moroccan interrupts to say it's time for mensa.

Inside Mensa della Solidarietà (Table of Solidarity), which is run by Comunità Missionaria Porta Aperta (Open-Door Missionary Community), cafeteria-style tables line the room. Migrants make their way to the food window for their helping of the day's meal: Sicilian-style rice with peas and carrots, potato frittata, and a roll. Others have already found their seats.

An African in his 20s carries a cap similar to the one Bob Marley wears in photos, colored bright yellow, red and green. He makes them himself, says Sr. Maria Stella, one of the mensa's coordinators. The man grins proudly at his work.

In the kitchen, two Sicilian women work the window, one balancing a stainless steel pot between both arms while the other scoops rice onto plates. Four other volunteers work an assembly line on a nearby table, spooning ice cream into cups for dessert. Another man washes dishes. He's been volunteering for years, Stella says.

"When the first batch of migrants started to arrive years ago and they were sleeping in the streets, he took them into his own house," she says in Italian.

Stella says almost 100 locals volunteer at the soup kitchen, which opened in 1999. They feed up to 100 people a day, including migrants and those in need.

Gaczol and Bara sit down next to a group of men they've met before. Emmanuel, 31, who declined to give his last name, says he stays home all day with nothing to do while he waits for his asylum documents to process. He's been in Sicily since 2014. He has yet to visit the sea — a 20-minute drive from the city center, where he lives.

"If I had friends, I would go," he says in English. "But it takes money."

He came to Sicily from Ghana to escape political unrest. His mother, father and brother are dead, he explains, looking up from his potato frittata.

"I was very sad," he says. "Now, it's OK."

Emmanuel, like many migrants who reach the shores of Sicily, worked as a laborer in Libya before paying a human smuggler to catch a boat to Italy. He worked there for one year, he says, but decided to leave when the situation got too dangerous.

"They would shoot people in the street," he says of the rebels in the area. "You would see it."

Patrick, another Ghanaian in his late 20s, smiles and remains quiet as he eats. The two have recently formed a friendship, Emmanuel says.

Before leaving, Patrick grabs a broom and begins to sweep the floors of the cafeteria. When he is sure the floors are absent of food, he says goodbye.

"See you tomorrow," he says to the volunteers.

Migrants among migrants

Since their December 12 arrival in Sicily, the sisters have slowly begun to navigate their way in a foreign country and in a new community.

Five sisters are based in Agrigento and six in Ramacca, a town of about 10,000 people on Sicily's eastern coast and a two-hour drive from Agrigento, but the two groups occasionally meet.

On July 10, for example, four sisters from Ramacca drove to Agrigento for the Festa di San Calogero, a street parade to celebrate one of two patron saints of Agrigento.

In the living room of the sisters' Agrigento flat, both groups talked to GSR about their experience in Sicily and the challenges they face in their new home.

"The communication is a challenge," Society of Sacred Heart Sr. Paola Paoli says of the multicultural living arrangements. Paoli, an Italian native who lives in Ramacca, spent two years in Congo (DRC) before applying for the project. Her roommates in Ramacca include sisters from Eritrea, Ethiopia, India and France. All 11 sisters have experience living in Africa.

The sisters account for eight nationalities, eight congregations and four continents. Each speaks at least three languages, and together, they speak more than 15. Two nurses and a finance major are also among the group. Until June, there was only one Italian.

Migrant Project/Sicily is not the first project of its kind. Based on a 2008 project in South Sudan involving both women and men religious, the project's core mission mirrors the realities of migration.

"It was quite deliberate," Murray says of the selection process. "They're migrants living among migrants. All the challenges you have of living in a multicultural, multinational community parallel some that migrants might have when they come."

Immersing the sisters in the new culture included a two-month preparation period in Rome, where they attended Italian and English classes as well as workshops on community-building, intercultural living and the migration realities of Italy and Sicily.

Combining the different charisms wasn't easy either, they agree. When Sr. Lemlem Digetai, an Eritrean of the Capuchin Sisters of Mother Rubatto who lives in Ramacca, received the information about the project from her superiors, she thought about it "for months," she says.

"Because it's international and intercongregational, it was not easy," she says. "But [the superiors] mentioned the word 'mission.' It pushed me. The mission, you can't reject."

Some have lived in other countries almost longer than their own. Sr. Francesca Scandella of the Capuchin Sisters of Mother Rubatto, for example, had to relearn Italian after living in Brazil for 20 years.

In Rome, they decided together how they'd incorporate the different charisms into their daily routine, including prayer and community life.

Then there is the discussion of food.

Paoli wants pasta every day for lunch, says Sr. Sara Ersado, an Ethiopian native of the Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady who lives in Ramacca. Everyone bursts into laughter.

"It's just that I eat everything," Paoli replies with a laugh. "She doesn't eat mushrooms, she doesn't eat cheese, she doesn't eat tuna." More laughter.

Laughter has helped them overcome the challenges, they agree. But the differences are unimportant, Scandella says. "The important thing is we are together. And we always manage to find a way to make each other understand."

'It's really about making connections with people'

The sisters' multicultural backgrounds have made it easier to communicate with migrants. Speaking their language, for example, provides an instant connection, Paoli says. "They are considered objects in the boats. To have a person who treats them like they are human, to listen to them, helps."

"The difference with us is that there are so many organizations that are working with specific task forces," Gaczol says. "But for us, it's really about making connections with people, listening to them, accompanying them."

Gaczol recalls one day this spring when she went to the beach to relax. There, she met an African boy staring out at the sea.

"I learned he was going just to look back in the sea because he lost two of his friends when they were coming," she says. "The two of us were going to the same point for totally different reasons."

Others recall similar stories.

"I remember one Libyan boy full of tears," Bara says of a 22-year-old she recently met at the port in Agrigento. "The same day he arrived. Full of tears. So we spent some more time to talk." The listening consoled him, she adds.

Many migrants come to Italy in hopes of reaching wealthier European countries like Germany and Sweden, the sisters say. But asylum-processing times have proven lengthy, and many are left waiting — sometimes for years.

"People are going mad, they are so miserable," Emmanuel says of the waiting process.

Many wish they had stayed home and taken their chances, Ersado says. "After a while, they reach here, and the reality is very, very different. So they say, 'My family paid this money . . . for what?'"

The sisters acknowledge that their resources are limited in helping migrants in a tangible way. Their hope, they say, is to provide a presence.

"We can't help them," Paoli says of the migrants' frustrations, citing long processing times. "We can only listen and try to comfort them, accompany them, be a listening ear. And many times, they appreciate that."

A potential new world order

The possibility for another Migrant Project/Sicily site in Caltanisetta is in talks, Murray says, but there are no concrete plans at the moment. The project could also serve as a model for potential projects throughout the world, she added, including along the borders between North and South America and between Asia and Australia.

She is confident about one thing, however: Working and living among differences "is the future."

"I feel we are like a sleeping giant in terms of how much more we can achieve when we begin to network and collaborate and work together across congregations," Murray says.

UISG also hopes to add researchers and data collectors to their team of sisters in various sites across the world to track women religious working with migrants.

The mission will remain unchanged. Meeting migrants in the streets, building relationships and making personal connections make up the foundation.

"We are on the cusp, really, of a new world order, where we are going to have to live with difference," Murray says. "And the difference won't be miles away. The difference will be beside us."

[Traci Badalucco is an NCR Bertelsen intern. Her email address is tbadalucco@ncronline.org.]

Related - Greek Council for Refugees speaks with NCR about migrant crisis

Q & A with Sr. Florence de la Villion, part of the UISG Migrants Project