On his six-day swing through three East Coast cities this week, Pope Francis will be warmly welcomed by diplomats, members of Congress and princes of the church. The young and the marginalized so close to his heart and mind — homeless men and women, prisoners, students — are also prominent on his itinerary.

But because the pope's stay will be short, he may not have the opportunity to spend significant time with many of the religious women whose grit and compassion power many local ministries and institutions in Washington, D.C., Philadelphia and New York.

Pope Francis, let us introduce Srs. Jeanne Clark, Mary Bourdon, Eileen White, Diane Guerin, and Carol Vale. Though this group is by no means representative of the many ministries that thrive on sister power, the women do represent unseen and unnumbered others active in working with vulnerable women, for social change and creation care, and in Catholic educational institutions.

It is probably too late to get them a calendar slot for this trip, but there is always next time.

Sr. Jeanne Clark

"I don't believe we can be connected to our soul unless we are connected to the earth," says Dominican Sr. Jeanne Clark, leader of the group that started Homecoming Farm on the grounds of the Dominican motherhouse in Amityville, New York. "We're not just looking to heaven as our home. This is our home."

Currently a 3-and-a-half-acre plot of land, the organic farm is funded in part by the 100 families who buy a share in it. Twenty percent of the produce is donated to a local soup kitchen.

A child of New York City, Clark has spent much of her career as a teacher and campus minister on Long Island. Her ministry has also included time in Virginia, Tennessee and Washington state, where she joined a community dedicated to nonviolence and to protesting the Trident submarine.

Clark, a Dominican for 56 years, has also been shaped by her work with Salvadoran refugees, both on Long Island and in Honduras during El Salvador's long and bloody war. When that conflict was finally over, Clark became a student of the natural world at another Dominican-run project, the 226-acre Genesis Farm in Blairstown, New Jersey. There, she became captivated by the writings of the late Passionist Fr. Thomas Berry.

"I began to see that the difficulties the Earth is having are not a problem of theology, it's a problem of cosmology," Clark says. "We don't really know who and where we are."

Once focused on all injustice perpetrated on humans, Clark began to widen her perspective to include not only people, but all living beings and the Earth itself.

"I began to see this as a way forward, a way that we can move towards being a global community together."

In Laudato Sí, Pope Francis' encyclical that urges humans to focus on the future of the planet, Clark says she hears echoes of the same vision: "The pope is talking about coming home to this kind of home together, because this is where we belong."

When she goes to Catholic schools to talk to students, Clark reminds them that on Earth, there is no such thing as throwing something "away" — what they discard remains on earth and returns to the soil, the water, the air.

Once the director of Homecoming Farm, Clark is still very active, both in traveling to local schools and hosting groups that come to learn about the land. In the year to come, the sisters at the motherhouse will decide whether to increase the acres devoted to farming. Though the community has the most open space in the local area, running the farm continues to be financially challenging.

Asked what she would say to the pope if she met him, Clark doesn't hesitate: "I would say a huge thank you. My gratitude to him is overflowing. He has articulated this vision of a global community, and his voice is being heard everywhere. "

"It's so needful that we come together and know that, as Jesus says, we are one. He's not only a voice of hope, but he's challenging us to change our lives. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you."

Sr. Mary Bourdon

Ask Sr. Mary Bourdon, who heads the Washington School for Girls, about the roots of the thriving, two-campus girls' school in one of Washington's poorest neighborhoods, and her mind flashes back to 18th-century France and the mission of her order's foundress, Claudine Thévenet.

"In a time of revolution, she educated young girls with an emphasis on those most in need of a quality education," says Bourdon, a Religious of Jesus and Mary.

Fast-forward the Thévenet vision a few centuries, and what do you get? A rousing success story: a tuition-free school for fourth- through eighth-grade girls that sets its students on a course to surmount the many challenges they face.

"Everyone wants to come to our school, but we want to serve those who wouldn't have the opportunity," Bourdon says. "We're looking for children in whose lives we can make a difference."

Born of innovative collaboration between the Religious of Jesus and Mary, the Council of Negro Women, and the Society of the Holy Child Jesus, the school's neighborhood-focused mission is to African-American girls.

"We're delighted that we have a foundation in faith and culture — the Catholic church and this rich African-American tradition," says Bourdon, who has had a multifaceted career that includes counseling, teaching, leading a program for volunteers in Haiti and directing a Maryland-based Catholic Charities office before she co-founded the school.

The Washington School for Girls launched in the late 1990s as an after-school tutoring and enrichment-activities program for fourth- and fifth-graders in the basement of an apartment building. It now boasts a $3 million annual budget, more than 100 students, and a program that includes counseling, support for families, and staff members that follow and support graduates, 98 percent of whom go on to successfully complete high school.

One of the schools is housed at Our Lady of Perpetual Help Church, "the mother church of the African-American Catholic church," which had lost its own parish school.

"It's interesting how these things happen," says Bourdon, who continues to build and nurture collaborative relationships locally and nationally as the school draws increasing attention and plaudits.

Bourdon says she's grateful for the pope's "energy, for his support, especially for seeing through rules and regulations to the hearts and souls of people, what people are seeking and struggle with. He certainly is a teacher and guide and role model."

Bourdon also finds that the pope's message stirs up deeper questions in her.

"It's very challenging to all of us. It's nice to say he's doing great things. But I'm asking myself: Am I living up to what he's saying?"

Sr. Eileen White

Sr. Eileen White is more than willing to take time out of her busy schedule as resident coordinator to explain the mission and purpose of Philadelphia's Dawn's Place, a home for victims of sex trafficking.

But when she understands that the purpose of my call is to laud her work, White, who celebrated 50 years as a Grey Nun of the Sacred Heart last year, firmly objects.

"I don't want to be featured," she says. "Dawn's Place is what is great. It's the more than 20 sisters who volunteer, along with Muslims, Jews and others, who make the house run smoothly."

The home provides hospitality and support services, including vocational guidance and psychological support, to 10 women aged 18 and older. The women must be willing to commit to the shelter's comprehensive program, which links them with vocational counseling and offers them social and practical skills they need when they leave. To enter the program, the women, many of whom have struggled with addiction, must be dedicated to embracing recovery.

White says many of the residents, who are both foreign- and U.S.-born, were sexually abused as children and teenagers and turned to a pimp who promised to take care of them. The women are referred by local police, the FBI, trafficking coalitions, prison chaplains and others they meet in their difficult lives that may include stints in rehab or encounters with the law. Occasionally, someone refers themselves.

Should White meet Pope Francis, she says, "I'd love to ask how the Holy Spirit achieved getting him elected. Beyond that, mostly I would want to encourage him to do what he's doing to make people, especially in the Catholic church but also throughout the world, understand that we are one and that one person's suffering is all of our suffering. Since the beginning of time, humans have often exploited one another. We have to find a way to find what is the very best in humanity let that take over."

Sr. Diane Guerin

Ask Sr. Diane Guerin about her job as justice coordinator for the Mid-Atlantic Community of the Sisters of Mercy, and she defines it as anything related to social concerns that needs to get done. Then, she adds: "There's quite a bit. Maybe that's why I get tired."

Guerin's portfolio includes environmental sustainability (a current focus for the Mercy community) and finding ways to tackle persistent racism in U.S. culture. She works out of the motherhouse in Merion, Pennsylvania, a leafy, genteel Philadelphia suburb.

Her educational background reflects the diversity of interests that has characterized her ministry: a bachelor's degree in English, followed by a master's degree in urban education and a doctorate that blended education with training in alternative dispute resolution.

In addition to serving as a teacher in the Philadelphia archdiocese for many years, Guerin also worked as a desegregation counselor in the Philadelphia school system and a program director for the city's Martin Luther King Center for Nonviolence. For a number of years, she ran her own conflict-resolution company.

As justice coordinator, Guerin has helped the large community addresses various areas of concern, including immigration, the role of women in society, and environmental justice issues. When she's not teaching college students how to network and lobby for social justice, she's keeping other Mercy sisters in the loop about upcoming legislative priorities or working with Mercy Investment Services, an ethically sensitive asset management program for the Mercy community.

"I think the structure [of the church] should be more inclusive of women. We have to look at other faith models that are more circular," Guerin says. "We have lost our ability to dialogue in the Catholic church. We really need to listen, understand and respect each other so we can connect at a deeper level and move towards needed inclusive changes in the Catholic church."

Guerin praises the pope for his exhortation to take in migrants and notes his decision to view justice issues through a holistic lens: "My constant mantra is that all concerns are integrated. One impacts the other. In [Laudato Sí], he talks about how we are not separate, but one, all part of the web of life."

"There's a need to educate people in such a way that they can hear what is being said and gather people around the issues. People don't really hear each other. I think we have to find a way to open people up to be able to hear. "

Sr. Carol Vale

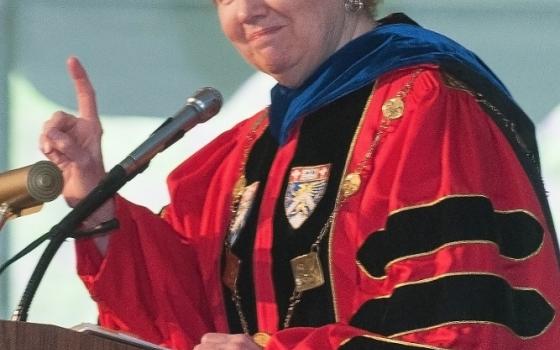

When Sister of St. Joseph and Chestnut Hill College President Carol Vale speaks, it is with ease married with a precision born perhaps of 23 years at the helm of one of the area's prominent Catholic institutions of higher learning.

As with most college presidents, there are few areas of life on the campus that don't engage her attention. Under Vale's leadership, the Philadelphia college, which now serves approximately 2,200 adult and traditional students, successfully made the transition 12 years ago from women-only to coeducational. The school has also expanded its footprint with an eye to preserving green space and moved to develop deeper ties with its neighbors in the vibrant, urban Chestnut Hill landscape.

"The changes [in higher education] have been very dramatic," she says, noting the accountability demanded of institutions of higher learning, oversight from regulatory agencies, and vigilance on the part of parents, who want to make sure their son or daughter will find employment upon graduation.

Although the college has moved to add a Disabilities Office and support for students who need emotional support, "the greater challenge is the underprepared students who simply have not had the background that they need in terms of writing and mathematics. You have to offer them some kind of remediation, which changes how quickly they can finish the program, through no fault of their own."

"It's not that they can't succeed, it's just that they need help," she says.

In addition to a constant stream of local challenges that require decisions, Vale is active nationally and abroad as a Catholic educator. She has served as the chair for the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities, the Association of Colleges of Sisters of St. Joseph as well as the Southeastern Pennsylvania Consortium for Higher Education — and that's just for starters. Vale is a published theologian with a degree in historical theology from Fordham University and is a member of multiple boards and organizations.

"I absolutely think it's the best of time to be a sister in the United States today because women religious have gained respect and admiration clearly articulated not only by the Catholic faithful, but by others as well," she says. "They have served with compassion at great personal cost for decades, helping transform immigrant churches into ones that serve many races.

"If I had to say something to the pope, I'd ask him to recognize the equality of women with men by including women in the governance and life of the church," Vale says. "At every level, the church has benefited from the inclusion of women, and I would hope that women would be allowed to participate fully in the decision-making processes of the church.

"I think," says Vale with the confidence of a leader keenly aware of the risks and rewards of making difficult decisions in an ever-changing environment, "that he is a man who is absolutely equal to the task."

[Elizabeth Eisenstadt Evans is a religion columnist for Lancaster Newspapers, Inc., as well as a freelance writer.]