Four minutes to 4 p.m., Sr. Mary Nyarko stepped down from a large pickup truck, the most luxurious mode of transportation for her that day, which started at 7 a.m. It made the bumpy mud road from her pontoon ferry ride to the small village where her sisters run a rural health clinic a bit more bearable.

The Holy Spirit Missionary Sisters' clinic isn't just far from Nyarko's home in Ghana's capital, Accra, it's far from everywhere. Even the patients who need care often walk two or three hours to reach the clinic, which means they may be too late for medical care to help them. With limited resources and staffing, the three sisters who run the facility have their hands full and days packed serving at least 1,000 patients a month.

The clinic was established as part of the congregation's mission to "continue the healing ministry of Christ," the clinic's administrator, Sr. Mary Nkrumah, said. Initially, sisters from Germany and the U.S. had come as missionaries to Ghana in 1946 and years later sought isolated areas to care for those far from established medical care.

"Most of the people around here [were] dying of snake bites, some more dying when they deliver [babies], some also were having all kinds of other diseases. People were not really taken care of," said Nkrumah.

There weren't even roads to get patients to health facilities, so Nkrumah said the sisters went to the people.

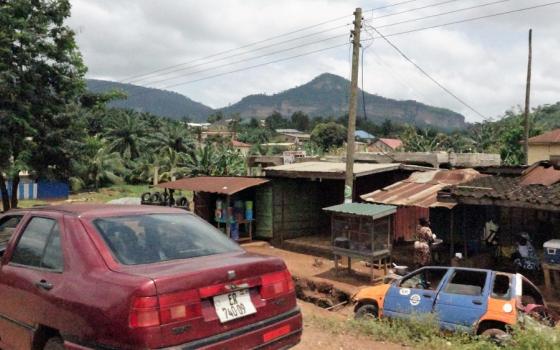

After creating hospitals in towns like Nkrawkraw, the sisters first based their remote missions from a town called Donkor Krom, the district capital of Afram Plains. Small villages of a few homes apiece line muddy roads; they have small-scale crop farming and raise chickens, and in areas on Lake Volta, people catch and smoke fish. As a sister for 25 years, Nyarko spent time working at the health center in Nkrawkraw and knows the sisters who worked in the rural areas well. She described sisters taking daily outreach trips to secluded villages and finding it impossible for many of them to make the return trip the same day. They saw the area near Kwesi Fante was particularly neglected. In areas where there were no roads at all, Nyarko said the sisters spoke with local chiefs about getting accommodation for a few days at a time. Soon, the community built a small brick structure for accommodation and the clinic launched in the late 1990s.

"At Donkor Krom, there's a hospital there, so at least they can manage," said Nyarko. "But this place, nothing. So that is how Kwesi Fante started."

The long trek to the village

Nyarko's trip from Accra to Kwesi Fante took about nine hours, mostly using public transportation. By private car, it would take around 5. Stopping in multiple towns via tro tro (passenger van), shared taxi and a ferry pontoon, Nyarko tries to go to the clinic every other month, or when the need to take care of administrative business arises. After 28 years in the congregation, 14 of which she lived in neighboring country, Togo, Nyarko now coordinates mission activities under the Holy Spirit Missionary Sisters leadership in Ghana.

"It's always better when you have your own car," Nyarko mentioned of the white Toyota Helix pickup truck that Nkrumah and their driver pulled up in at the pontoon port on Lake Volta. It was another 45 minutes before she arrived.

Nyarko describes Kwesi Fante as a sub-district; about 61,000 people live there and in the surrounding villages, she says. It is a village so small it's not listed on online lists of Ghana's population. By contrast, Accra has nearly 1.6 million people.

The clinic itself is separated by walls within the village; there is land for more buildings, but funding makes it difficult to expand accommodation or healthcare facilities. Without consistent internet and cell service, the Mother Josepha Convent runs with a water tank and solar power lights when electricity inevitably goes out. The clinic is a couple dozen meters from the convent, in the same gated compound. There may be assigned government-appointed medical staff, but it's hard to retain qualified workers after their mandatory national service is up.

Arriving at the convent by 4 p.m., Nyarko dropped her small travel bag in her guest room and joined her colleagues for lunch. The others had already eaten, but they saved Palava sauce, made with kontumbre (a Ghanaian vegetable similar to collard greens), rice, boiled yam and plantain, for whenever she would arrive.

Three sisters live at the convent now: Nkrumah, the administrator; Sr. Eunice Tamea who runs the pharmacy, and Sr. Petra Manalo who is a midwife. They work with nurses on site, some community health nurses who visit villages in the region, medical assistants, pharmacy assistants, one other midwife, and lab technicians.

Life at the clinic

Returning from checking on a mother in her maternity ward, Manalo joined Nyarko and the others at the dining table. She had been up all night, delivering the baby of a woman who has HIV.

"We are only two [working in the ward]. So, most of us, we take a double shift. And you know, [we are] always ready when they call us to help them. Sometimes we don't have time for ourselves," Manalo said holding back tears.

She faced a big learning curve getting used to this small community she joined just a few months earlier. She came to Ghana three years ago from her home in Indonesia, as a Holy Spirit Missionary Sister. Manalo first needed to study English, and then get re-certified in midwifery in her new country.

Working without oxygen to help mothers delivering babies, Manalo says they try their best, but she struggles knowing that they often are not able to make it to the nearest hospital, which is at least two hours away on unpaved roads. She sees mothers who arrive with nothing, who can't afford the trip to the hospital anyway.

Many patients can't afford to pay for services, though the sisters are patient in waiting for payment from those who can. Regardless of anyone's ability to pay, the sisters offer care. "We come here, [and try to] save the life. We have only faith, and we have mission and vision to save the life. Just that one," said Manalo.

Through the window of the laboratory are thatched roofs of the villagers. Most live in huts made of mud, with straw and branches arranged on top.

Nkrumah explained that villages like Kwesi Fante, consisting of 10 to 20 homes, typically lack electricity, internet or cell network services, decent roads, and even water. Because there are few amenities, she says, it's hard to find qualified staff willing to stay here.

Recently, one medical assistant who said he was going to visit his family never returned. Nkrumah feels the need to build better accommodation for the clinic staff, to entice them to stay, but that takes funding that the sisters don't have.

Challenges in the village

"It's very difficult for somebody to be in the village for almost 18 years," said Amatus Arko, the clinic's microscopist.

He knows he's unusual in that he's worked with the sisters for all these "good years," as he calls them. His family lives four or five hours away in the city of Kumasi, where he says his children can receive a better education. He travels to see them some weekends, and they stay with him in Kwesi Fante during school vacations. He admits that it's difficult but not unusual for fathers to live away from their families in Ghana.

Originally from Sunyani, about a seven hours' drive away, Nkrumah moved to Kwesi Fante about a year ago. She joined the sisters in 1993, professing in 1997 before teaching in Ghana and eventually spent four years in social pastoral work on a South African mission. After working in a Holy Spirit Sisters' hospital a couple hours from Kwesi Fante and returning to school to study public health, Nkrumah arrived in Kwesi Fante about a year ago and realized how much the clinic needs her leadership.

While their services are appreciated, Nkrumah knows if they could create more of a hospital atmosphere, with an accredited doctor, surgery theater, and proper outpatient department, their patients would be better served.

"We have medical assistants; they have also their limits," said Nkrumah.

Lab technician, Aboo Thomas arrived only a year earlier, too, from Ghana's Upper West region. He explains the manual blood cell counting processes used to diagnose malaria, sickle cell disease, and tuberculosis. One out of 10 patients here typically has malaria, so Thomas calls their area "endemic," yet his process is only an estimation since they don't have hematology analyzers to count specific cells.

When the facility first opened, Nkrumah says they had fewer than 200 clients a month because people were afraid they would be referred elsewhere, meaning the long trip would be for naught. Now, she explained, they at least know they'll likely get drugs for their ailments, but her staff struggles to provide emergency care.

"For instance, the road now, because of the rains, it is totally out of use. So, we take [patients] to Donkor Krom; [it takes] about three hours before we get there," Nkrumah described. And when we go to Nkrawkraw, you have to also only [wait] at the ferry, [often] for more than two hours, before we can cross."

Since they can't perform transfusions or offer high-tech solutions, the sisters need to refer sick patients and pregnant women facing complications to a bigger health facility. Nkrumah knows even their ambulance isn't quick enough to help those referred patients.

"If the case comes, and it's already in a bad state, before you get to the hospital, the person is gone," said Nkrumah.

Knowing it's not always possible for positive outcomes, the sisters and their nurses work toward preventative care. They sustain outreach programs, making their way by truck through woods along unpaved roads to visit communities and offer vaccines or medical advice.

Nkrumah, though, isn't deterred.

"I'm happy to be here because the people need us," she said. "Sometimes you get there, there's no road — you have to create the road for yourself. …It's a kind of joy, you know."

[Dana Wachter is a freelance journalist and digital storyteller based in London, Ontario.]