Twelve sisters from six countries share a common mission in the streets and crime-ridden areas outside San José, Costa Rica — working with homeless people and people living in poverty, distributing food, helping to provide shelter and offering spiritual support.

Through their work, the Misioneras de la Caridad de Madre Teresa de Calcuta (Missionaries of Charity of Mother Teresa of Kolkata) as the congregation's Costa Rican mission is called — help continue the vision of their order's founder, who is being canonized Sept. 4.

Despite the challenges, the effort helps change lives for the better, as Superior Sister Marinus said in an interview with Global Sisters Report.

Sister Marinus, who has been with the order 27 years and knew Mother Teresa, speaks with enthusiasm about its mission. "It really fills my life," she said. "The Mother always told us we are not going to do great things in our life, our life is very simple. . . . Whatever we do is small things, [which] we know we are doing directly to the person of Jesus, because this is our charism."

Sister Marinus first learned of the Missionaries of Charity at age 10 as a Catholic school student in her native India.

"I knew that the life they were leading was very simple, and I felt very at home when I entered. That was my place," Sister Marinus said.

She described Mother Teresa's holiness as coming from one certainty: "She knew, as she always spoke to us, each person is a Jesus Christ."

"The main thing which has attracted me so much was her simplicity, and her uniqueness in attending the people, one by one," Sister Marinus said. "For Mother, everybody was precious," whether a beggar or a president.

"For me, it's the same privilege we have with the poorest of the poor," she stresses. "They are the Christ, and it is a privilege to serve them."

Sister Marinus said that, carrying out Mother Teresa's legacy is a great responsibility. "I lived in the time of Mother, with my own eyes I saw Mother, how she prayed, how she lived. . . . Many times I have felt unworthy, because I know the work that we do is a work of the Lord. Like St. Peter, I can say: 'Lord, I'm not worthy for such sacred work, but because you call me, you make me worthy.'"

Headquartered in Coronado, a town 25 kilometers northeast of San José, the Missionaries of Charity run two homes in Costa Rica. One in Coronado houses an average of 50 elderly indigents; the other in Limón serves some 75 homeless persons.

Their major operation is in downtown San José, where every Tuesday evening, on the La Merced parish lawn, they provide dinner for about 300 street persons.

The order arrived in Costa Rica in 1986, as the result of an effort by Fr. Leonel Chacón, then the parish priest in Coronado. At that time, he entrusted a home he had opened five years earlier for poor and sick elderly to two of Mother Teresa's missionaries.

The missionaries' presence, for the routine stay of four or five years in Costa Rica, has grown to 12 sisters who are from six countries — Argentina, Guatemala, India, Mexico, Nicaragua and Venezuela. (Missionaries do not work in their native countries.)

Sister María Elizabeth, a Mexican religious, said they share Jesus's work with the poor, "Like Mother Teresa, we have to move forward, satiating, in the poor, their thirst for Jesus."

"We try to see Jesus in them. . . . Here, the people are very simple, they're humble. . . . They know how to behave, and it's quite pleasant to serve them," she said.

As the sun sets, outside the church's east gate, needy men and women begin to line up, waiting to enter the premises, where warm meals, cooked by volunteers, will be distributed.

The procedure follows an order, starting with the requirement to wash their hands, aided by volunteers, at a sink on one side of the church. Then two other volunteers hand them a ticket each, which is exchanged then for a meal.

They eat sitting on long wooden benches brought out from one of the church's offices or settle elsewhere on the parish lawn. Some engage in dialogue as they eat, while others remain silent, in an atmosphere of safety and peace that sharply differs from the often violent street reality they face daily.

Sister Marinus and Sister Charles — both from India — usually come from Coronado for an opportunity to interact with recipients, who include those who have housing but face critical economic and social situations.

One of them is Patty Hernández, a 33-year-old Nicaraguan single mother of four — ages 12, 9, 7 and 6 — who hasn't found a steady job in two years.

Although she has been in Costa Rica for more than two decades, Hernández has not regularized her immigration status, a situation that has become a major obstacle for her to work. Without an identity card now, "They don't give work, [but] I have four little kids, and I have to find the way to give them some food," she said, as Sister Marinus handed her two dinners.

"I haven't had a job for two years, and sometimes one looks for something, like ironing clothes and stuff. Sometimes, there's nothing, so one has to come here, at least to take some food for the little ones," she said, adding that she comes to La Merced when she can round up the money for five bus fares.

She had managed to find a few formal jobs — in security, as a house worker, at a restaurant. "I'd do everything," the young Nicaraguan said, and, smiling, commented that the job with a private security company "was OK. It's a job that I like, that I like a lot, yes."

She is one of the thousands of Nicaraguan nationals who have migrated over the 309-kilometer border to Costa Rica because of a lack of opportunities in their home country. Costa Rica's population of 5.6 million includes about 600,000 foreigners with different immigration situations.

Nicas, as Nicaraguans are popularly known throughout Central America, make up 75 percent of the immigrants. Most work in low-skilled and low-salary labor fields, mainly the agricultural, domestic, construction and security sectors, as well as in the informal economy.

After their mission work at La Merced, the sisters go to a nearby municipal dormitory where some of the homeless cared for by the congregation have an overnight place to dine, sleep and shower.

The Centro Dormitorio (Dormitory Center), which opened in 2010 and is managed by Fundación Génesis (Genesis Foundation), houses an average of 115 people. There the sisters provide Tuesday dinners, medicine and spiritual assistance on their weekly visits.

The homeless who want to stay in the dormitory that night have to stand in line on the sidewalk outside for the chance to draw a white chip for a one-night stay, or a red chip that denies entry. The procedure is repeated daily.

At first, shop owners on the block complained that the presence of the indigents in a commercially busy sector was driving their clients away, an attitude that gradually changed.

Realizing that some of the homeless were becoming regulars, the managers structured a plan to guarantee space for them and also to encourage them to study: Those who registered to finish school or high school, and who regularly attended class, would have a permanent place without the need to take part in the daily raffle. Women and elderly persons also have a secured spot.

Many saw this as an opportunity to both save a spot at the dormitory and complete an education as a chance to improve their lives.

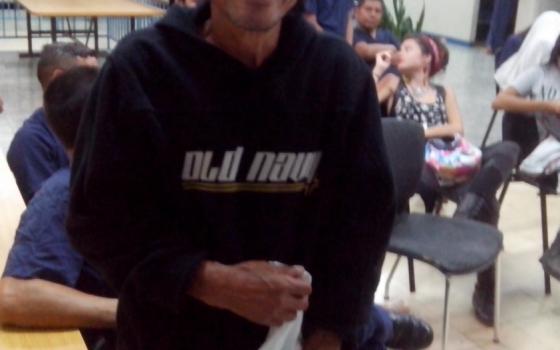

Luis Javier Chaves, in his 50s, is one such case. He is the son of a mixed couple — Nicaraguan father, Costa Rican mother — and says, "I tell everybody that I'm a nicarricense [Nica Rican]."

Javier said his father left his mother alone to raise him and his two sisters. "Mommy was our father and our mother."

Before coming to the shelter, Javier recounted, he was addicted to crack and alcohol. "I was cartoneando [cardboarding, or sleeping on or under cardboard scraps] for several years."

"I was skinny, was sick," he said, and "God's Glory! God's Glory! They opened this [dormitory], which, at the beginning, was an experiment, first to help us but also to lower the homeless population in downtown San José. And it has worked."

He said he understood the local opposition in the early days. "We homeless, in general, are people who have no place anywhere, because of our appearance, because of our smell, because of our way of speaking, because of our behavior, because of all those shocking things," he detailed.

Javier first came to the dormitory in 2010. "I liked it, of course. Who wouldn't like it — after many years sleeping under pieces of cardboard, out in the open with the cold of the night — a warm, bed, dinner — God's Glory — clean pajamas, taking a bath?"

Two years later, he took the opportunity to study and secure a fixed spot at the dormitory, finishing high school in two years.

But most importantly, he said, "I learned to love myself, I even learned to be responsible with myself, and I learned to set myself goals and dreams, and I found myself a little room where I began to live by myself."

A friend offered to pay for his entrance exam to the public Universidad de Costa Rica, which he passed. "You should have seen the joy," he said. Now Javier is studying to be a librarian with an emphasis on education.

The lesson this nicarricense has learned is "to believe in oneself — first in the Glory, then in oneself. And that's where recovery begins," he concluded.

This is, precisely, the fruit the sisters seek for their labors: improving lives, assuring people in need that they are cared for and loved by God.

They work with similar populations in Coronado and Limón, and with families at risk of poverty and violence in capital districts such as Los Cuadros and Los Colochos, where organized crime rules.

At a Tuesday food distribution at La Merced, Sister Marinus spoke of the order's charism to save the souls of the poor — "and for us one of the poorest of the poor is the people always in the street."

"It doesn't matter who and what they are and what they do, but we know they are the image and likeness of God . . . and our charism is so much focused on that," she explained. "Doing this small gesture . . . we want to manifest to them that God still loves them and he cares for them, and he is still present in the world."

The people are grateful that the sisters come the distance from Coronado to bring them this one plate of food each week. "Many times, when we meet them on the street, they have a special love for us, for the sisters. They know we are for them."

[George Rodriguez, a freelance correspondent based in Costa Rica, has reported for Reuters and other international news agencies.]

Related - Mother Teresa could always face up to the situation, a first-hand account