Benedictine Sr. Joan Chittister is known as an inspiring writer and speaker, a tireless advocate for women's rights who refused to be silenced by the Vatican, a prophet often turned away in her own church and an unflagging champion for peace and justice.

In the biography Joan Chittister: Her Journey from Certainty to Faith, journalist Tom Roberts reveals the interior Joan Chittister: her difficult childhood in Pennsylvania, the young woman who found both refuge and purpose in her religious vocation, the public figure whose brilliance produced a body of written work that will stand as a profound expression of spirituality and women's concerns in this era.

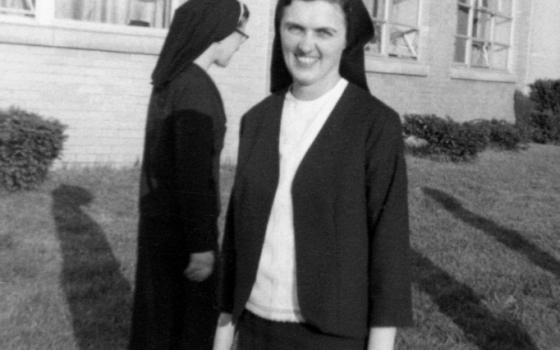

This excerpt from Chapter 3, "The Monastery," describes a young Chittister determined to fulfill a desire she had since early childhood to become a nun.

______

They may not have been aware of it, but in their kindness to the new student the Benedictine sisters had sealed the deal. Before her freshman year of high school was completed Chittister knew she would become one of them. The moment couldn't arrive soon enough. At the end of her first year, Chittister rang the prioress's bell at the school.

"How did I know you weren't supposed to ring the prioress's bell? They were forever ringing bells, and I saw they had a card there with the sisters' bell numbers, so I just went and hit '1.' That was the prioress."

Mother Sylvester, the prioress, came out of her office. She looked a bit bewildered at seeing this youngster in front of her. Chittister got right to the point. "I said, 'Mother, I would like to talk to you about being a Benedictine.' "

She didn't get beyond that. The prioress asked her age, and when Joan said fifteen, the nun told her that the order did not take girls younger than sixteen.

Chittister went back to classes at the academy and the following April showed up once more at the monastery. Mother Sylvester again answered the door. Chittister announced that she was now sixteen. The nun, who by this time knew Chittister, looked puzzled; she had obviously forgotten the previous year's encounter. "Last year, I came to ask you about being a Benedictine," Chittister said. "You told me I had to be sixteen." She explained that she had just had a birthday and wanted to talk about entering the community.

The response was a shock. Mother Sylvester told her once more that she would be unable to join the community.

"I said, 'Why not?'

"She said, 'Because you're an only child. We don't take only children.'

"I said 'Why not?'

"She said, 'Because some day your mother is going to need you, and it's not fair to her and it's not fair to you. No, dear, we do not take only children.'

"I was stunned. I just stood there. She didn't say another word. She simply turned to go back in her office and closed the door in my face. I finished whatever I was doing. Then I ran all the way to 23rd and Holland, as fast as my legs could take me."

She wanted to get there before Dutch [Harold "Dutch" Chittister, her stepfather] got home from work so that she could tell her mother about her conversation with Mother Sylvester.

She was worried about her father's reaction to her desire to become a nun. When Loretta [her mother] heard why the Benedictines had turned her down, she told her daughter to call the monastery and request an appointment with Mother Sylvester.

That evening, Loretta and Joan were led into the large parlor of the monastery on 9th Street. Loretta asked Mother Sylvester if the child's understanding of the conversation that afternoon was correct. Mother Sylvester confirmed the order's rule, one that, from her point of view, was considerate of the family. Loretta had a different view.

She told Mother Sylvester that it wasn't Joan's fault that she was an only child and that, as her mother, she did not want her daughter's life affected by that fact. She said her child was free do whatever she wished and that her ambitions had nothing to do with her mother. "I did not have her to use her as a domestic nurse when she got older," Loretta told Mother Sylvester. "She has a life to live."

She said if the order did not want Joan in the community for other reasons, she could understand. But she also put Mother Sylvester on notice: "When that kid makes up her mind to do something, she does it. Now she's going to enter somewhere, and it does not have to be here, but she's going to enter because if she wants that, that's where she's going."

Mother Sylvester asked Loretta if she meant all of that, and Loretta assured her that she did. "I don't want my life hung around her neck," Loretta said. She wanted her daughter to be happy.

The prioress responded, "Well, the entrance date is September 8th. Maybe we should begin to talk."

"That was it," said Chittister. "I wound up here, and the rest is history."

She finished the school year and took up a hectic schedule that summer. Most days began with seven o'clock Mass, followed by a catch-up Spanish class she needed. Immediately after class she would walk a few blocks to 10th and State Streets to a florist shop, open it for the day at 8:30, and work there until noon. At noon she would walk to 10th and Parade Streets to an ice cream and sandwich shop, where she began work at one in the afternoon. She would leave the ice cream shop at five and run to 27th and Parade to work at a diner, where her day ended at eleven at night.

Chittister worked the three jobs to make money to buy a list of items she needed for entrance to the order. It was part of the ritual of the day, and Dutch, who had provided no money for Catholic schooling, was not about to pay her way into the convent. Dutch had prohibited her mother from working, so his was the only income the family had. In fact, Chittister said that she never told Dutch her plans about the convent until just before she entered.

On the list to be purchased were black shoes ("They were a big deal"), a place setting of silverware ("Damask Rose was the pattern that I bought") and blankets (purchased on a layaway plan at the local Sears & Roebuck store). She also had to purchase luggage and a big steamer trunk.

Whatever time was left in the summer was spent in normal teenage pursuits, including days at the local beach and going out with a boyfriend named Bobby. She had dated boys from the time she was fourteen, making sure in those early years to stop holding hands a few blocks from home because she knew Dutch was worried about her going out with boys. In this matter, her mother intervened sternly on her behalf and let Dutch know that what Joan was doing "was perfectly normal." That seemed to have put the subject to rest. The teenage Joan was free to hold hands and to invite boys to the house.

As the summer of her sixteenth year wore on, however, she had to take the first tangible step on the transition to life in a monastery. She had to tell the boy she was dating. "I was entering in September and now it was late July," says Chittister. "He was making plans for the next year and my mother said, 'Don't you think it's time you tell Bob that you aren't going to be there next year? Are you going to wait and let him find out on the first day of school?' "

Soon after that conversation, the two teenagers spent a day at the beach "and at some point over the baloney sandwiches I said, 'I'm entering the convent in September.' "

The shocked young man answered, "You're kidding!"

She told him she wasn't. He tried to persuade her to wait. She said she saw no reason to delay the decision. She didn't want to wait any longer to start her new life. "That was really the conversation. It got very quiet after that. It wasn't much of a fun date after all. If I remember correctly, he took me home. He wasn't going to waste any more time either."

As she notes in a history of the community that is highly autobiographical, the Erie Benedictines that Chittister joined in 1952 were fashioned by "the rigor of routine." Religious life, which would undergo such drastic changes over the course of the next two decades, was at the time, and had been for years, "marked by five basic characteristics: it was reflective, regular, focused, clear, and effective."

Women involved in that monastic routine were, on most practical counts, only a few degrees removed from their married and childbearing sisters of that era. They cooked, they cleaned, they had no personal money, they looked after the children in schools and, "at the highest levels of ecclesiastical jurisprudence, they lived at the mercy of male superiors," Chittister writes. "The church, the courts, and the family all gave men control of a woman's property, her intellectual development, her personal behavior, and her public participation."

In one significant respect other than celibacy, the nuns were different from most other women of that era. They lived in a world of ideas — encountering on a daily basis scripture, the psalms, writings of church fathers and other great thinkers of the tradition — and they went to college.

That was a significant marker for many of them, even if they were required to take classes around the demands of classroom teaching.

They were regularly assigned to teach in the order's schools before they had earned their full degrees. More than a few times in interviews, sisters of a certain generation in the Erie community mentioned the opportunity for education that they otherwise would not have had as one of the motivations for entering religious life. Though Chittister's early life was an extreme example, it also was not uncommon to hear that women who joined had arrived from abusive situations or dysfunctional or poor families. The Benedictines had a reputation in Erie as the "blue collar" community. The "Mercies," sisters of the Mercy order, were viewed as the next step up the ladder, and the "Josies" or St. Joseph sisters, occupied the top rung of the socio-economic ladder.

While those general perceptions may not precisely represent the reality of that time, it is not surprising that Chittister found herself comfortably at home with the other students at St. Benedict Academy and determined to join the order. She immediately found acceptance at the high school and a welcoming community in the convent. "I kind of dropped into a situation with people I really loved," she says. "I wasn't doing penance. I didn't go into religious life to do penance or to give things up. I really saw it as a place of peace and harmony and goodness."

Sometime in the week or two before she would enter the convent, Chittister left on a cocktail table in the family living room some brochures and other materials that made clear her intent to enter the convent.

It was her way of communicating with Dutch.

She walked in on him some time after that and said, " 'Dad, that's my stuff and I want you to know I'm entering St. Benedict's on Monday.'

"He said, 'I know.' There was no conversation. That was it."

Loretta told her at some later date that Dutch let her know the Friday before Joan entered that he would not be going to work that Monday but would be accompanying them instead, unless Loretta said no.

She told him she would never say no, and neither would Joan. He said to Loretta, "I told them my kid was going away on Monday and I couldn't come in to work."

Early on the day she was to enter, Chittister met a good friend and the two girls attended Mass. On the way home she stopped at a vending machine and "bought a fistful of candy to get rid of the last money I had." She returned home and finished packing.

Later that morning, packed and ready to go, she came into the family living room to find Dutch, in his Sunday best brown suit, with her mother. "I went over to him and I put my arms around him and he grabbed me, he just hugged me so hard. I said to him, 'Daddy, I promise you, if I don't like it, I'll leave.'

"And he held me really tight and he said, 'Goddam it, I hope you don't.' Meaning, I hope you don't like it. And he was crying. I'll go to the grave with that memory in my heart."

He accompanied them to the monastery and waited outside in the car until the ritual of being taken into the convent ended. That was to be his practice over a number of years when he drove Loretta to visit her daughter. Most of the time Dutch would sit in the car. On the occasions when he met the sisters they were cordial and gracious with him.

"The nuns were so kind to him, they were so kind to her," said Chittister.

"As much as he wanted to hate them, it was pretty impossible."

Chittister entered the order on September 8, 1952, the youngest of a class of seven postulants who were beginning their education in the utter predictability of religious life: after getting up at five, there was a half hour of Lauds, followed by a half hour of spiritual reading, a half hour to forty-five minutes at Mass, and a half hour of breakfast before heading off to school.

On that first day she and her mother entered the monastery through the front door on 9th Street. It was a big deal, because ordinary kids didn't go through the front door. They had to enter through a porch at the back of the building.

Much of the initial portion of the first day is a blur in her memory.

The soon-to-be postulants and their families were ushered into a large parlor, and if there was a program of any sort, she doesn't recall the details. Before long, the new arrivals were taken off to a different part of the monastery to get dressed in the postulant's habit: a little veil and a cape, shoes, hose and a dress, all black. Then they were taken back into the parlor to say goodbye to their parents.

It was around noon when, with the goodbyes completed, the seven postulants moved off in a line down a corridor that separated the monastery from the high school, past rooms along the corridor that had large windows and past refectory doors that had stained-glass windows at the top. "What I remember about that day is that I was the youngest, and therefore I came at the end of the line. They were walking along in front of me and the shadows were bouncing along with each kid — bing, bing, bing, bing — and I looked at all those shadows and said to myself, 'I'm going to be following these kids around for the rest of my life.' We laughed about it for years, whenever anybody asks, 'Does anyone here remember anything that happened on that day?' "

That evening is clearer in her recollection. The girls were assigned to a dormitory, and for the first time in her memory she went to bed without the fear that arguments and violence might erupt nearby at any moment.

She experienced "phenomenal relief, phenomenal, phenomenal relief. And happiness," she said. "And, the unmentioned emotion," she adds, pausing long seconds before continuing, "was my fear for my mother and my shame for having left her. I really struggled with that for a long time. Could I possibly be happy without her being happy?"

That night she looked at the ceiling and listened to the quiet and realized: "I had never felt that kind of security. I had never felt that safe. I was literally surrounded, you know. I was surrounded by people.

"I wasn't alone, for the first time in my life. And these were good people, and there was nothing to be afraid of."

That feeling would be accompanied by an awareness that "it wasn't so much security as it was certainty that the world ... that this world had a genuine stability to it, that my energies were not going to have to go into protecting myself from it, enduring it, fighting it, being controlled by it."

Excerpted from Joan Chittister: Her Journey from Certainty to Faith by Tom Roberts, published by Orbis Books, Maryknoll, NY © 2015. All rights reserved. www.orbisbooks.com

[Tom Roberts is NCR editor at large. His email address is troberts@ncronline.org.]

Related: New dimensions of Joan Chittister's life feature in biography, author says