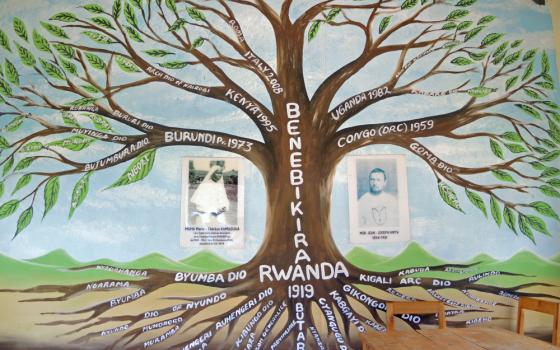

Like nuns everywhere, the Benebikira Sisters, the oldest indigenous congregation in Rwanda, have sisters who are teachers, nurses, pharmacists, formators and administrators. But they also have religious with a unique title: Sister Listeners.

"The genocide created many problems, some people don't want to live because of what happened," said Sr. Marie Venantie Nyirabaganwa, the superior of the Southern Province of the Benebikira sisters and the women's head of the Association des Superieures Majeures du Rwanda, the national umbrella group for women and men religious*.

The 1994 Rwandan genocide, when up to a million people were killed during 100 days of fighting and in the chaos before and afterward, lurks under the surface of every interaction, even though 23 years have passed since the killers laid down their machetes.

The country has successfully emerged from some of the physical devastation after the genocide, the economy growing at impressive rates. Skyscrapers reach towards the heavens in the capital of Kigali and well-paved roads crisscross most of the countryside.

Now the country is perched in a delicate balance, as the people try to honor the memory of those killed while firmly looking toward the future. This balancing act comes into focus each year on April 7, the anniversary of the day the genocide started. It marks the beginning of a three-month period when the country turns inward to remember.

"There are many problems in Rwanda, and many people have mental problems because of the genocide," Nyirabaganwa said. "Those who killed have their own problems, and those who lost people due to the genocide have their own problems."

"Especially mothers who lost all of their children and husbands, or the young ones who lost all the members of their family," Nyirabaganwa added. "Many people just need someone to listen. Some have HIV [rape by HIV-positive men was one of the tools used to brutalize during the genocide]. There are different problems with families."

Six Benebikira Sisters are dedicated to full-time listening. Some of the sisters run group therapy sessions, others do individual counseling as needed. They studied different approaches, including pastoral work or counseling, and go for continuing education on a regular basis, Nyirabaganwa explained.

The role of listener is less formal than therapist but fits better with Rwandan culture, she said. "The sisters in charge of listening are helping them spiritually. We help them to resolve and get answers to their problems."

Other congregations, including the St. Boniface Sisters, adopted the model of "listeners," finding ways to blend psychological support with Rwanda's unique needs and culture. The role of these listeners is especially important in the springtime.

"In April, the country shuts down in memoriam for about two weeks. It's a period of remembrance," said Nicole Sparbanie, a Peace Corps volunteer from Chicago who works with the Bernardine Sisters in the village of Kamonyi, 25 miles outside of Kigali. Each village or district has its own memorial, usually a tomb and a mini-museum. Additionally, each district observes the anniversaries of major events that happened locally during the 100-day genocide.

"All the school kids walk together and they read the names of people who died in that area. They tell the stories of the victims, and there is also art and music," Sparbanie said.

Because every local anniversary is marked annually during this 100-day period, newspaper headlines and radio shows are full of reports about them, keeping the focus on the country's difficult past even as people try to move on.

Although the government severely limits free speech inside Rwanda, some activists and international organizations quietly question whether the government is using the memorials to limit opposition and maintain its authority. Official government memorials, including the Kigali Genocide Memorial, call it "the Genocide against the Tutsi," which erases any reference to the thousands of Hutu who were killed, sometimes while protecting Tutsis. The title also negates any reference to crimes against the Hutu before the genocide or revenge killings that took place afterward. President Paul Kagame is Tutsi, although it is illegal to speak of ethnicity in Rwanda, as part of a government initiative called "Ndi Umunyarwanda" ("I am a Rwandan").

"The recognition of committed atrocities and seeking of forgiveness is emphasised as a central aspect of this 'Rwandasition' project," Patrick Hajayandi, a senior project leader for the South African organization Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, wrote about the Rwandan memorials. "However, the recurring theme is the need for all Hutu to seek forgiveness from the Tutsi." He worried that by consciously ignoring the pain of Hutu victims, the government is creating resentment that could explode in the future. "While memorials have a useful function, if they are not inclusive, they do not necessarily promote reconciliation," he added.

Sisters are finding ways to work within the acceptable government framework of memorials to offer their counseling services to all of the victims — both Hutu and Tutsi, regardless of what roles they played in the genocide.

Sisters are an integral part of the government observations. They lead discussions and prayers during the memorial period, providing spiritual support during the official events and outside counseling on a personal basis.

"We work together with the government," said Sr. Donatille Mukurabayaza, the local superior for the Bernardine Sisters in Kamonyi. Mukurabayaza trained in Capacitar, an international mindfulness training aimed at reconciliation in conflict zones. Capacitar emphasizes internal balance and peace more than external sharing that the Benebikira "Listening Sisters" provide. Both programs allow the sisters to offer counseling and spiritual support to groups and individuals privately, and also to take a leading role during the memorial period in April.

"The government gives the main line to follow for reconciliation, and then the civil society makes its contribution after that. The government has different programs, so we do those, and sometimes we improve upon them," she said.

Mukurabayaza noted that government support is essential to their work. "Sometimes you may have a good vision but when there's a barrier with the local authority you can't achieve anything," she said. "In Rwanda, the government has the same vision as the people – all Rwandans are the same, all Rwandans are equal, all people must contribute to the welfare of the people."

Sr. Laurentine Musomayire, the assistant project manager for the Benebikira congregation, said they try to provide an example to villagers still struggling with reconciliation. "The sisters are joined together, we didn't separate ourselves [into the Hutu and Tutsi tribes during the genocide]," she said. "We talked together, we lived together, we ate together without any problem. If we weren't together, more sisters would have died. When people came and tried to kill sisters from one tribe, the sisters protected them and refused to give them up."

This also meant that, in some places, entire communities of sisters were murdered because they refused to give up Tutsi sisters to the Hutu killers. The Benebikira congregation lost 22 sisters, both Hutu and Tutsi.

"During the genocide, they destroyed everything," she said. "They stole so many things, even this building was destroyed. It was terrible. We had to start from nothing. We continued to work with the people, tried to talk to people here about what happened, we tried to teach them. Some people were angry at the church."

The church played a complicated role in the genocide. In many instances, priests and sisters actively supported the killers, especially when victims fled to the churches for refuge and were handed over to the killers. International courts indicted four priests and two sisters for war crimes in connection with the genocide. The two Benedictine sisters, Sr. Gertrude Mukangango and Sr. Maria Kisito Mukabutera, received 15- and 12-year sentences, respectively, for their role in relinquishing 7,000 Tutsis who were hiding at their Sovu convent in southern Rwanda.

The Catholic Church in Rwanda officially apologized for the Church's role in the genocide on Nov. 20, 2016, the last Sunday of the Year of Mercy. However, the Rwandan government questioned the sincerity of the statement and called the apology an attempt to "[exonerate] the Catholic Church as a whole for any culpability in connection with the genocide."

Pope Francis made an official apology when he met with Rwandan President Paul Kagame on March 20. Francis "conveyed his profound sadness, and that of the Holy See and of the Church, for the genocide against the Tutsi," the Vatican said in a statement. "He expressed his solidarity with the victims and with those who continue to suffer the consequences of those tragic events."

In Rwanda, activists believe that the Catholic Church has an important part to play in reconciliation despite its checkered past. "[These] institutions have a big role to play because they're the ones who have access to people," explained Honore Gatera, the director of the Kigali Genocide Memorial, at an event commemorating International Holocaust Day in February. Representatives of the Vatican and the Israeli ambassador to East Africa also attended the memorial.

"[The Church has] a huge responsibility," Gatera said, especially in their schools. "They must be involved in commemoration and memorialization events and activities, but most importantly, they must be part of the education journey that we have started."

Sisters are leading this journey, by reaching out to people wherever they feel most comfortable to talk, including their homes or places outside of the church. As the country marks another year since the genocide on April 7, the sisters providing psychosocial support are even busier during the memorial season.

"Emotions are so high around this time, even if you haven't been through the genocide," said Jean Claude Nkulikiyimfura, the director of a high school in the Rwamagana region of eastern Rwanda. "All schools are on break from March 28 to April 21, so kids can go back to their communities," he said. People crave connection and comfort, sometimes causing them to turn to risky behavior. "Emotions are so high, we find that's a time when some girls get pregnant," Nkulikiyimfura added.

Although the memorial period can be the most intense, Mukurabayaza, the Bernardine sister, stresses the need for communication and understanding during the whole year. "Each person needs to learn to accept each other and respect each other," she said. "Every person has to express what he or she is feeling. You need that exchange."

*An earlier version of this story gave an incorrect title for Nyirabaganwa.

[Melanie Lidman is Middle East and Africa correspondent for Global Sisters Report based in Israel.]