Four years ago, Anna Sung Thi Nhu Y was in second grade and performing badly at school. She was living with her uncle because her parents were in prison for illegal transport of heroin.

Her uncle, who lives in a remote area in Dak Nong province, could not afford her school fees, so he sent her to St. Teresa Hostel run by Mary Queen of Peace sisters. The hostel provides free accommodation, food, health care and education to students from ethnic groups in the Central Highlands.

Y, who is Hmong, tried to fit in with the other children in the hostel, although she missed her parents and siblings. She told visitors she wanted to be in prison.

"I missed my parents very much," she said.

Thanks to nuns' support as parental figures, Y now is an outgoing sixth-grader who acts as emcee at gatherings in the hostel. Last year, the Catholic student was rewarded for her good performance in school with new notebooks and received first Communion. She also paid a visit to her mother in jail.

The hostel, established in 2013, is based in Buon Ma Thuot City, the capital of Dak Lak Province, in the Central Highlands.

"The hostel aims to give opportunities for ethnic students to study well at schools in the city," said Sr. Mary Nguyen Thi Thuan, head of the hostel.

The hostel admits students who are from remote villages and interested in studying, Thuan said. Orphans and those who are from poor families are also selected to stay at the facility while they attend first through 12th grades at public schools in the city.

There are some 200 students from 14 ethnic minority groups living at the hostel in this academic year.

Thuan said most newcomers perform poorly at village schools because their families live in poverty and pay no attention to their studies, leading the students to wander away for play or to work on farms. Thuan said teachers at the public schools in remote areas ignore their duties because of lack of government inspection.

"Many fifth- or sixth-graders could not speak, read and write Vietnamese fluently," Thuan said. "Their education levels are just like second-graders."

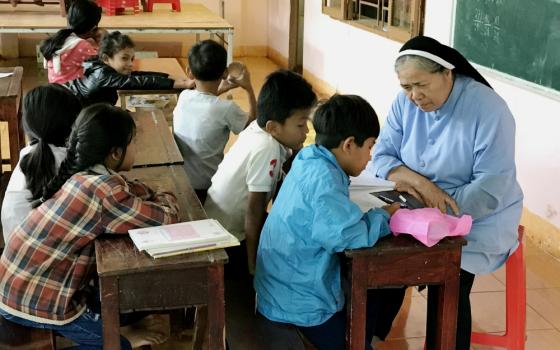

The nuns and hired tutors help students at the hostel review subjects after class. Foreign students also volunteer to teach students English and living skills.

Students are also taught to do housework and cook and learn good hygiene and how to use toilets. In their villages, they urinate or defecate in the open air and bathe in streams.

They also learn catechism and good behavior and attend daily Mass.

"After some months living at the hostel, students can integrate themselves into their schools and community life at the hostel. They dare speak with classmates and strangers," Thuan said.

She said students also spend one hour each day growing vegetables and fruit trees on a farm, raising poultry, and making organic fertilizers from dry leaves and poultry feces. Vegetables, fruit and poultry are used for their food.

"They are given free accommodation and food, so they need to work so as to treasure what they receive," Thuan said.

Local benefactors offer the hostel food and other materials to support the students. About 10 students each year who want to go to college after high school will be given scholarships sponsored by the benefactors.

Some leave the hostel after a few months because they are bullied by classmates, fail to keep pace with other students, speak Vietnamese badly, and are afraid of strangers.

Sr. Teresa Nguyen Thi Bich, who tutors elementary students at the hostel, said many hostel students graduate from colleges and universities and work in hospitals and schools and for foreign companies. Some join orders and study theology abroad.

Others return home and get married after finishing high school. Bich said they bring benefits to their villagers after leaving the hostel: "They teach villagers how to prepare food in hygienic conditions, do housework, cultivate crops effectively, teach them Vietnamese, take patients to hospitals because they can speak Vietnamese and count money, [and] encourage other children to continue their studies."

She said they also hold liturgical services and religious ceremonies at their communities and teach catechism to villagers.

"They serve as lay leaders in places where there are no resident priests and nuns," she added. Dak Lak Province is home to various ethnic minority groups, many of whom suffer the government's religious restrictions: Priests from other places are banned from visiting local people, who are restricted to gathering at their homes for prayer.

Thuan said the nuns cannot afford to admit all students sent by their parents. Each July, potential students from villages come to stay at the hostel, reviewing subjects, doing daily activities and getting accustomed to the learning environment for one month. The nuns select those who are interested in school and have good behavior. Those who have many siblings and are orphaned will be admitted, too.

Many refuse to enter the facility because they do not want to live away from their families.

Last July, 80 students attended the summer activities at the hostel, and two-thirds of them returned in the fall.

Francis Xavier Y Sam, 20, finished high school in June and lives at the hostel, helping the nuns manage the students.

"I am extremely grateful to the nuns who gave me opportunities to finish high school and learn various skills and practical experiences for my life," said Sam, who has seven siblings who dropped out of school early.

Sam, who is from the neighboring Dak Nong Province, said no one from his village has studied at college. Most people left schools early because of poverty and poor performance at school, he said.

"I love to stay here because I have close friends and good teachers and sisters. I see them like my relatives," Y said with a smile.

[Joachim Pham is a correspondent for Global Sisters Report based in Vietnam.]