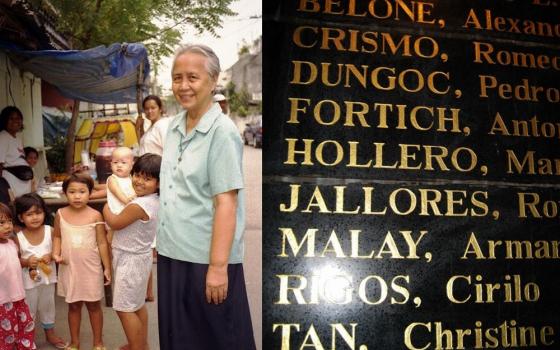

Remembered in a special way on Dec. 10, International Human Rights Day, are 298 persons who fought and suffered in the Philippines, including many who gave their lives, to end the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos and martial rule that lasted 14 years. Their names are etched on the black granite Wall of Remembrance of the Bantayog ng mga Bayani (Monument for Heroes) in Quezon City, Metro Manila. Candles are lit, flowers are offered by relatives and friends and activities or programs are often held on Dec. 10.

The names of nine religious sisters are among 28 church persons, including Catholic priests (diocesan and religious), deacons and bishops, as well as pastors from non-Catholic churches, who were active in the anti-Marcos dictatorship movement. Several of the priests died violent deaths or are among the desaparecidos, or the "disappeared."

Marcos' martial rule lasted from 1972 to 1986. Toppled through a People Power uprising in 1986, Marcos and his family lived in exile in Hawaii and other places. He died in exile in 1989.

The nine religious sisters or "Bantayog sisters," as they're known in the Philippines, came from different congregations and backgrounds — some from wealthy families and with varied educational degrees. Some ministered to political prisoners and their families, others focused on aiding striking workers, particularly sugar cane and factory workers, mistreated under the Marcos regime. Some spent time in prison themselves for their resistance to the dictatorship.

"It is difficult to imagine these religious sisters, some of whom were born to wealthy families and had privileged backgrounds, feeling the sufferings of the poor, leaving the security of the convent to be on muddy ground and confront fully armed soldiers," Maria Cristina Rodriguez, executive director of Bantayog ng mga Bayani Foundation, told Global Sisters Report:

"But they did, they risked their lives, entered detention centers, bringing out prisoners' letters in secret, embracing striking workers, hiking up and down hills to be with communities harassed by the Marcos military."

Four of the sisters — all belonging to the Religious of the Good Shepherd — died in a shipwreck in 1983. They are known as the "Cassandra martyrs" because of the name of the boat they were in, the MV Cassandra: Srs. Mary Catherine Loreto, 39, Mary Virginia Gonzaga, 42, Mary Consuelo Remedios Chuidian, 46, and Mary Concepcion Lourdes Conti, 46.

The other five sisters continued working in various ministries after the political change and died of natural causes. Sr. Mary Bernard Jimenez of the Carmelite Missionaries died in 1984 at age 61; Sr. Asuncion Martinez of the Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary died in 1994 at age 84; Sr. Maria Violeta Marcos of the Augustinian Missionaries of the Philippines died in 2001 at age 64; Sr. Mary Christine Tan of the Religious of the Good Shepherd died in 2003 at age 73, and Sr. Mariani Dimaranan of the Franciscan Sisters of the Immaculate Concepcion died in 2005 at age 81.

Below are some of their stories, based on from reporting by this writer who had interviewed several of the sisters for other articles over the years, and information from Bantayog.org.

First detained sister

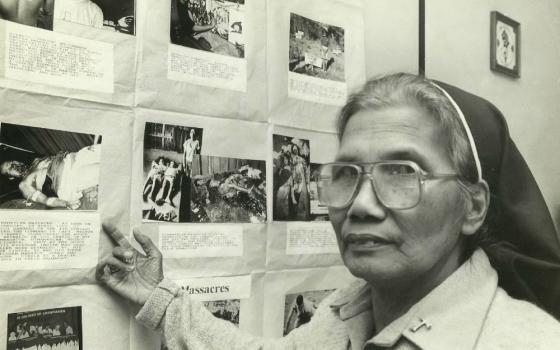

Dimaranan of the Franciscan Sisters of the Immaculate Conception was the first and one of two religious sisters who were detained when martial law was imposed and was behind bars for several months.

Multi-awarded and internationally known for her human rights work, Dimaranan, whose academic background was in the social sciences, was a vocal critic of the Marcos regime. After her release from prison (she was accused of subversion), she was among the founders in 1974 of the Task Force Detainees of the Philippines of the Association of the Major Religious Superiors of the Philippines. She headed up the Task Force Detainees for 21 years and steered it to become a refuge and source of strength of political prisoners and their families. She went to remote places with fact-finding teams to investigate and document military abuses. The book Mariani, a Woman of a Kind (TFDP, 2001) is about her life and human rights work.

She told this writer in 1983: "The oppression we are suffering is only part of a global trend, so in terms of approach we have to link up with human rights advocates abroad, with other Christians."

Sr. Cresencia Lucero, who now heads the Task Force Detainees of the Philippines and the Justice and Peace desk of the Association of Major Religious Superiors in the Philippines, recalls: "Sr. Mariani and I belong to the same congregation. My vivid memories of her were the days and nights of going from one police station to another in search of those abducted, and going to morgues to identify the dead. As a religious she integrated her activism with her vowed life."

Care for political prisoners

Jimenez, a Carmelite Missionary, was one of the earliest volunteers and became the coordinator for Metro Manila for the Task Force on Detainees of the Philippines, even though she was in her 50s when martial law was declared. Political prisoners who had few visitors got special attention from her, and she worked for their release, going to military offices to plead for their freedom.

Cassandra martyrs

The four Good Shepherd Sisters who died in the sinking of the MV Cassandra in 1983 were all working in the Mindanao region, south of the Philippines.

Born to a life of privilege and with studies abroad, Chuidian held several important positions in the congregation before choosing a difficult assignment in Mindanao during the martial law years. She ministered to farmers and indigenous groups as well as communities displaced by the government's war against communist rebels.

In 1982, Chiudian was appointed superior of the Good Shepherd sisters in Davao City. She was elected chair of the Women's Alliance for True Change and coordinator of the Rural Missionaries of the Philippines is the southern part of Mindanao.

Conti organized and led the Community-Based Health Program in the Tagum Diocese in Mindanao. She helped communities understand the social and economic factors that had to do with their poor health, an activity considered subversive by the military at that time.

As a Task Force Detainees of the Philippines worker, Loreto visited military camps, searched for missing persons and traveled to remote areas to reach out to families of victims of human rights violations.

Gonzaga was the superior of a small community of Good Shepherd sisters in Lanao del Norte in Mindanao, where tension between Christians and Muslims were common. Theirs was an "apostolate of presence."

The four sisters were among the more than 600 passengers of the MV Cassandra, which sank off the coast of Mindanao while headed for Cebu province. There were just 184 survivors. The sisters were with a group of mostly human rights workers headed for Cebu province to attend a conference. Seven other justice and peace workers died in that accident.

Survivors said the sisters put their own safety last and attended to the passengers as the boat sank.

Courageous and creative

When martial rule was imposed in 1972, Tan was the provincial superior of the Religious of the Good Shepherd in the Philippines. Elected in 1970 at the age of 39, she was the first Filipino to hold the position.

She broke new ground and instituted reforms that inspired the sisters to explore new ministries for the poor. Tan also exposed them to Asian spirituality and invited resource persons from different Asian religions. She was a Zen practitioner.

As head of the Association of Major Religious Superiors of Women in the Philippines in the 1970s, she participated in militant movements against tyranny. Her militancy and outspokenness caused her to be called to the Vatican and face chastisement. She remained undeterred. Unknown to many, she provided refuge to wanted activists on the run. Because of her connections and stature, she could visit high-security prisoners, among them former Sen. Benigno Aquino Jr., who was assassinated in 1983, and others accused of subversion and "inciting to rebellion."

After her term as provincial superior was over, she continued to be involved in various causes, among them, the anti-nuclear campaign and the anti-dictatorship movement. In 1986, newly installed President Corazon Aquino appointed Tan to the 48-member Constitutional Commission that drafted the 1987 Philippine Constitution.

Her comfortable upbringing and frail health notwithstanding, she and several sisters opted to live in a Manila slum area where they organized livelihood programs and Bible study sessions. She lived and worked there for more than 20 years until her death in 2003.

Tan told this writer in 1983: "Conventional religious life cannot respond to the screams of the people. We have to live like the 80 percent who are poor. Otherwise we will be a living lie to the people we serve."

Good Shepherd Sr. Rosario Battung says of Tan: "She was the courageous and creative leader not only of our province but also of the association of religious superiors of women and of formators. Fearless, she guided us during the dark years of martial rule."

Wake-up call

Marcos of the Augustinian Missionaries of the Philippines worked in the diocese in Negros province, which was then called a "social volcano" because of the labor unrest in sugar plantations during the Marcos dictatorship.* She considered her exposure to the sufferings of sugar workers as her "wake-up call." She also helped political detainees by working with Task Force Detainees of the Philippines.

When a group of Augustinian sisters decided to separate from their congregation for a "refounding," Marcos headed the new congregation. Sr. Cecilia Bayona, current congregational coordinator for Augustinian Missionaries of the Philippines, describes Marcos as having heeded the "call without reserve and shared her life and dreams with the people she served, steadfast in faith to the end, for justice and human rights."**

Baptism of fire

Martinez of the Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary spent most of her life in the congregation's expensive schools for girls, but upon retirement during the martial law years, realized there was life beyond the confines of school and convent.

In 1972, she joined the Rural Missionaries of the Philippines, a task force of the Association of Major Religious Superiors in the Philippines, and served as its head. She later joined another Association of Major Religious Superiors in the Philippines task force, the Urban Missionaries.

She befriended workers at the La Tondeña Distillery and was told in 1975 of plans for a strike at this major liquor factory despite a martial law decree prohibiting labor protests. She supported workers by participating in a picket line. Of the strike, she said: "It was a triumph for workers and for many religious, a baptism of fire. Salvation history was happening before my eyes."

In her advanced years, she tried living for a while in a depressed area in order to be with the workers and slum dwellers who affectionately called her Sr. Asun. Although called back to the convent because of her frail health, she continued to be involved in labor issues.

Wall of Remembrance

The first 65 names were engraved on the wall in 1992, and every year names are added. On Nov. 30, Andres Bonifacio Day, a holiday honoring the revolutionary hero who fought against Spanish colonizers, 11 more names were added to the wall during a three-hour program and ceremony, including that of diocesan priest Fr. Jose Dizon, who died in 2013. The names of all 298 were read one by one.

The Wall of Remembrance stands some meters away from the 45-foot bronze monument, created by renowned Filipino sculptor Eduardo Castrillo. The monument depicts a defiant mother holding a fallen son.

The monument, the commemorative wall and other structures at the Bantayog Memorial Center are dedicated to the nation's modern-day martyrs and heroes who fought to help restore freedom, peace, justice, truth and democracy in the Philippines.

In documenting the lives of the sisters, Bantayog researchers discovered "their countless contributions to the cause of justice during the dark years," director Rodriguez says. "Their faith gave courage and strength to the desperate as they themselves found liberation in serving the people's needs."

Editor's note: Details about the lives and sacrifices of each of the honorees are at bantayog.org.

* An earlier version mischacterized the birthplace of Sr. Violeta Marcos.

** An earlier version misstated Sr. Cecilia Bayona's position with the Augustinian Missionaries

[Ma. Ceres P. Doyo is a journalist in the Philippines. She writes features, special reports and a regular column, Human Face, for the Philippine Daily Inquirer.]