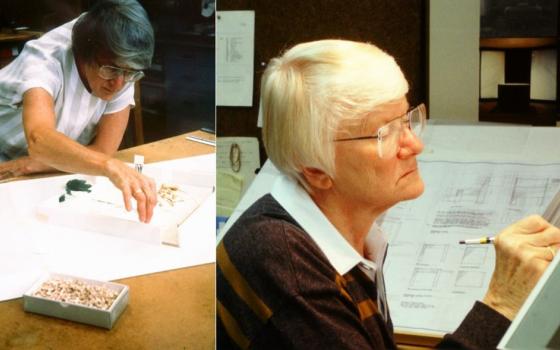

Dominican Srs. Barbara Chenicek and Rita Schlitz, award-winning designers of sacred space, long ago embraced the notion that art is as much about what’s deleted as it is about what’s included – and added their own twist: by becoming one with the communities who hire them, they themselves disappear.

Not physically, of course. But the two consider it “important that we are not somebody outside of [our clients] imposing ideas on them, so we try to erase the ‘we’ and ‘they,’ ” Chenicek said. “We join them in their times together, during prayer and meals. At some point, they do not consider us to be outside of themselves.”

A project they started in August 1980 changed the way the team approached their work. They’d designed space for Bon Secours Hospital in Grosse Pointe, Mich., and also for the Ursuline community in Chatham, Ontario. But when they were asked to renovate the Dominican Chapel of the Plains in Great Bend, Kan., they really began to think about their process.

“The leadership group wanted their whole community to be renewed,” Chenicek said. “We realized we had to think of what posture we wanted to take as we were being invited into chapel spaces. We decided we would approach each project as servants, to be one with them.”

Schlitz added: “Integration was what we were after. We’d go in and find that everything was a hodgepodge of what everyone had wanted through the years. We wanted everything to be integrated, to be one.”

They strived to make their work organic and holistic.

“We wanted to design space that enables you to express well-being in the heart of yourself, to be a threshold to know all is right with you and that you are in the holy,” Chenicek said.

Schlitz added, by way of emphasis: “Essentialness, clarity, truthfulness.”

In 1983, that renovation of the chapel in Kansas won the Grand Prize in the 10th annual Interior Design/IBD competition, a collaboration between Interior Design magazine and the Institute of Business Designers. To quote the magazine’s article about the award: “It marks, quite likely, the first time ever that two women, both full-time members of a religious order and practicing design professionals, too, have been officially honored by the industry for an installation reflective of such eloquent simplicity and beauty.”

From teachers to makers

Last year was the 40th anniversary of INAI Studio, located on their community’s campus in Adrian, Mich., where the two collaborate to design contemporary sacred space.

Their journey began in response to the Second Vatican Council’s call to women religious for renewal. “Vatican II fired us up,” Schlitz said, speaking of women religious in general, as well as herself, Chenicek and their community.

At the time, both women were college professors for St. Dominic College in St. Charles, Ill. “We were changed completely” by the council, said Chenicek. “We just wanted to step aside from the privilege we’d been given and get knocked around. We wanted to be leaven in the world.”

During a silent retreat in Schlitz’s apartment, the two had similar experiences. “We both felt called to go home to Adrian to form a studio where people could witness work being done by artists,” Chenicek said. “Kind of like the stoneworker we’d see under the bridge near the college where we were teaching. We considered him a real witness, and we wanted to be like him: to show people what it is about art that grabs people.”

Given a year’s sabbatical by their leadership council, Chenicek and Schlitz studied painting and metalsmithing, respectively.

“They told us to become what we were called to be,” Schlitz said.

Up until that time, the two had been artists who’d only taught. Chenicek says. “We were in this cycle of learn, teach, learn, teach. We wanted art to mean something, not just be something that somebody learns.”

By 1973, they had a building on the Adrian campus – the maintenance building that housed, among other things, the laundry equipment.

A compatible pair

They began thinking of a name for their studio.

“We wanted a short vowel with a long vowel,” Chenicek says. “We don’t like artificiality. We wanted the name to mean something.”

They considered several languages and settled on Japanese because they felt it “had depth. The word inai is a transitional word, which means within or inside,” said Chenicek. “But it is not a space word. It’s a moment of time.”

They started creating space installations because “our belief was they were a big evolution of art and more profound than anything that could be put on a wall,” Chenicek said. “They were often a provocative statement on the culture.”

Known today for their contemporary sacred space designs, which often include tapestries to hang in the spaces, the two are passionate about what they do.

“We conceive everything together,” Chenicek said. “We start with an empty space, then go apart to pray. We share our ideas – some are horrible but at least one idea usually stands out.”

The marriage of space and spirituality continues to delight the women, now in their 80s.

“Ours has been a search into the dimension of space, its quality and ability to awaken presence and perception of the holy,” Chenicek said.

The two say they are aware of the very special gift they’ve been given in each other.

“One of the things that is so wonderful about our collaboration is that we work so well together. It doesn’t matter which one of us comes up with the idea. What’s best for the project is what’s important. It’s something I could never have dreamed of,” Schlitz said.

At this, Chenicek said with a big smile, “To have been given the gift of such a partnership with two of us with such different personalities and areas of expertise is not something we expected. We have been called into the work of sacred space.”

[Kate Oatis is the owner of Oatis Communications. She does social media marketing for small businesses and writes occasionally for a variety of publications, including NCR.]

This story originally appeared as Space for the holy: Sisters serve with their art in the Ministry & Mission special section of National Catholic Reporter’s June 6-19, 2014 issue.