Much of the 100 acres of forest and prairie behind the Our Lady of Victory Missionary Sisters convent is already protected by a conservation easement, but the sisters want to protect the land from development forever.

The land has been a natural retreat for the Victory Noll sisters, as they're commonly known, for almost a century, with trails winding through the oaks, maples and sycamores, around steep ravines and prairie areas. A sister looking for peace and solitude needs only to walk a few hundred yards north of the campus buildings to find it.

The earth they love so much was brought here by the glacier that carved out the Great Lakes, the same glacier that, when it melted, released a torrent of water so large and so fast that it carved the Wabash River valley out of the soft sandstone of the area, creating the bluff now known as Victory Noll.

The sisters learned that their hill is the original bank of the historic Wabash River from Jason Kissel, the executive director of ACRES Land Trust, which purchases land and places it in restrictive covenants to permanently preserve it from development.

By the end of the year, the Victory Noll sisters' land will be sold to ACRES at a price based on fair market value — a move that many other communities of women religious in the United States have made to preserve land from development. In some cases, the preservation provides money that can pay for other expenses; in others, communities forgo a larger windfall by preserving land that developers would pay handsomely for.

"We thought about preserving the land ourselves, but we realized it would be ridiculous to reinvent the wheel when ACRES is already doing it. That's all they do is preserve land," said Sr. Ginger Downey, the Victory Noll sisters' general secretary and the sister who headed up the preservation effort.

"We already own a cluster of preserves in the area, including one right across the street, and this parcel fits with our goal of preserving the original bank of the Wabash River," Kissel said. "This land is significant itself, but it's also part of a complex of preserves in the area that are important."

Neither party would release a purchase price because final negotiations are ongoing; eventually, like other ACRES preserves, the land will be open to the public.

Downey said the sisters understand that development itself is not bad, but that they wanted to make sure it does not come to Victory Noll, no matter what happens to the 42 sisters who live on the campus.

Next door, the Quayle Run subdivision thrusts into the woods the sisters cherish so much.

"In the last 30 years I've been coming to Huntington, the amount of farmland that's been developed is amazing, and that's not sustainable," Downey said.

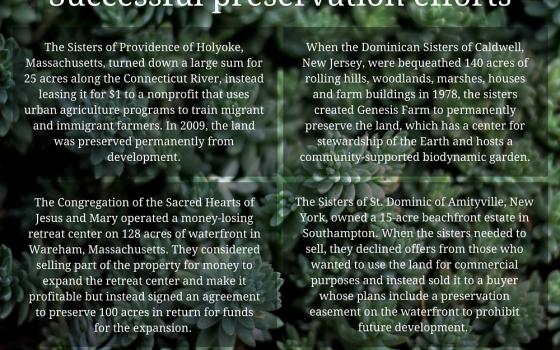

Religious communities around the country have been preserving land for years.

The Dominican Sisters of Peace in Plainville, Massachusetts, were given a farm and surrounding woodland in 1949. In 1991, they used the land to start a community-supported agriculture program, an organic garden and the Crystal Spring Center for Earth Learning. The land was permanently protected in 2008, and Crystal Spring partnered with the Massachusetts Land Trust Coalition to form the Religious Lands Conservancy Project, which helps other religious communities work with conservationists on preservation.

Sr. Barbara Harrington, who is on the Crystal Spring staff, said the work of preservation is more than just a strategy.

"It's a radical conversion to being a part of the larger Earth community," she said. "Who will inherit these lands? We were given them; do we want to take them as a kind of one-time capital gain, or do we want to give them back in the way so many of us were given them?"

Harrington said giving up land so it can be preserved is like the vow of poverty sisters take and is an idea that can be seen in the water so many preservation efforts affect: Just as the vow creates a life of simplicity and renunciation so that the sister can serve others, water has no form of its own, but is molded by its surroundings.

Water "renounces its form in order to give form to everything else," Harrington said. "It's self-forgetting. It offers its form so something new can be created."

The Sisters of Our Lady of Christian Doctrine, known as the Marydells, own 40 acres of prime real estate 30 miles north of New York City in Upper Nyack, New York. The sisters could have received up to $10 million from housing developers for the 30 acres they plan to sell, The New York Times reported, but instead will sell it for $3.1 million to a state trust that will make it park land that connects the three state parks it adjoins.

Sr. Veronica Mendez, the order's president, said the sisters could not bear the thought of developing the rolling hills with stunning views of the Hudson River. The money will go toward maintenance that has been neglected.

"It's beautiful," Mendez told the Times. "It really is a priceless piece of property, no matter how much money anyone offered us. This just seemed right."

Similarly, the Sisters of St. Francis of Penance and Christian Charity at Stella Niagara, New York, sold 29 acres to the Western New York Land Conservancy for $3.6 million. The land includes a quarter-mile of breathtaking panorama along the Niagara River, the Niagara Gazette reports.

Last year, the Sisters of the Sorrowful Mother sold their 155-acre Spirit Lake Preserve to a land trust for just over $1 million. The land, 30 miles north of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, was used as a rustic retreat, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported, but was expensive to maintain but valuable as a diverse landscape and habitat:

The lowland woods is topped with swamp white oak, yellow birch and red maple. Ephemeral ponds form in depressions during spring, providing habitat for salamanders and frogs. Red and bur oak, shagbark hickory and ironwood dominate the upland. The spring carpet is colored by wildflowers: wild geranium, spring beauty, trillium and jack-in-the-pulpit. An unnamed, intermittent stream cuts through a cattail marsh and wet meadow on the west edge of the property.

ACRES' Kissel said it was refreshing to work with the Victory Noll sisters.

"It used to be that my perception was if people are going to donate land or sell it at a discount, their primary motivation would be environmental reasons. But really, the majority of people say it's almost a moral obligation or a religious reason," Kissel said. "When you ask them why, in northeast Indiana, a lot of times the answer is, 'I think we need to be respectful of God's creation.'"

With the sisters, he said, he didn't have to dig for the answer.

"This one was the most blatant," he said. "They've actually taken the time to write down their land ethic. And when they showed it to me, it was the same as ACRES', though ours is not religious. The goals are the same. So it was fun to work with a group that had explicitly religious reasons for preserving land."

Downey said preserving the land was much more important that getting more money for it.

"We put a higher price on keeping it green space and keeping it for future generations," she said.

[Dan Stockman is national correspondent for Global Sisters Report. His email address is dstockman@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook. He is a volunteer for ACRES Land Trust.]