Editor's note: In Part 2 of this series, Global Sisters Report explores the parallels between the unlikely community of women religious and millennial "nones" and their potential for a meaningful collaboration. While the decline in numbers at institutional congregations may be a discouraging trend to some, the union of these two groups may answer who could inherit the charisms that animate religious life today. Read Part 1 here.

______

Jerone Hsu doesn't like to describe himself as spiritual, because "it presupposes the existence of a spirit," he said.

But the agnostic, Taiwanese-American founder of a community collective for social good in New York City said he knows one thing without a doubt: "Had I been born as a woman half a century ago, I would absolutely be a nun. … If you wanted to do good in the world, this was your ticket."

The national Nuns and Nones conversations helped illuminate the similarities for 33-year-old Hsu, who said that "even though my lifestyle doesn't look anything, on the surface, like that of a nun, I have found through my personal relationships with women religious a great deal of mutual recognition in our shared devotion, intensity and structured practice."

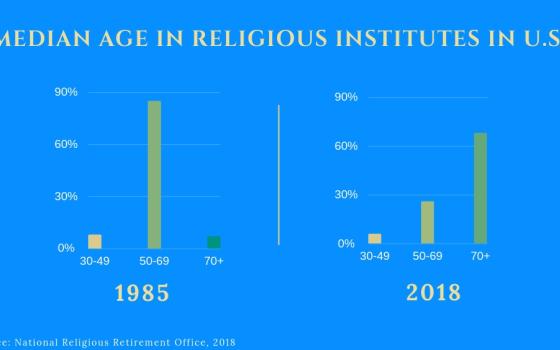

As a growing share of younger people consider themselves "nones," referring to the box they check next to religion, many religious congregations in the U.S. have been aging and diminishing in size and scope of ministry. But to the sisters involved in Nuns and Nones, these flipped numbers between surprisingly similar groups have become an invitation for a creative evolution.

St. Joseph of Philadelphia Sr. Carol Zinn attended the first Nuns and Nones gathering in November 2016 at Harvard Divinity School. Zinn immediately noted that the young people were running organizations "right out of the Gospel and Catholic Social Teaching. ... I was just absolutely awed."

Through her conversations with the group, Zinn (executive director of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious since May) has learned that millennials are interested in a life of spirituality, solidarity, service and sustainability, both financially and as a way of life. And what the "nones" see in women religious, she said, "is this very long story, like centuries, of living lives of spirituality, solidarity, service, in a way that has been, in fact, sustained. That's the core attraction."

Many millennials — people ages 23 to 38 — are drawn to the movement to learn about spiritual practice, but for Hsu, the possibilities for learning also delve into the practical, such as the infrastructure that allows for communal living and finances. Sisters have long led a "lifestyle of security that we are very interested in learning from, and I'm interested in modeling on a smaller scale," he said.

Parallels

After Mercy Sr. Anne Curtis from Madison, Connecticut, attended the first session, she "had this amazing sense that it was like listening to our younger selves in many ways," she said, echoing Hsu.

But Curtis still sensed a "spiritual longing" among the millennials that was not being satisfied by institutional religious entities, leaving them unsure "how to step into that" spiritual hunger.

Conversations usually begin with prompts — such as "What is bubbling up within you at this particular moment?" — to kick off conference calls or weekends together.

Sr. Mary Dacey, of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Philadelphia, said, "I have gotten more than anything I have given in this experience."

"They brought me back to my own integrity as a woman religious, not just by what they were searching for, but by the questions they asked," said Dacey, a former president of LCWR. "They reminded me of how I was when I was discerning my religious vocation. And quite honestly, when I was discerning my vocation, I don't know that I had the breadth of desire; I believe that I was called by God, but their questions were all encompassing."

One question in particular struck Sr. Judy Carle, of the Sisters of Mercy West Midwest Community, after a night of hanging out with the millennials in Burlingame, California. "What's your spiritual practice?" they asked her.

"They didn't ask the question, 'what do you believe?' … To me that's helpful in any interreligious dialogue; maybe doctrine or belief is not the first way of entering into a spiritual exchange," she said. Instead the conversation ventured into contemplative practice and charisms.

However, the more the millennials learned about the 2012-2015 doctrinal assessment, in which the Vatican investigated LCWR on whether it was following church doctrine, the more they wondered why the sisters would stay in an institution that questioned their devotion to the mission of the church.

Katie Gordon, a 27-year-old from Grand Rapids, Michigan, who founded a local branch of Nuns and Nones, said that talking about the investigation helped her understand a stark difference between the two groups. The millennials felt offended on behalf of the sisters, asking them how they could stay in such an institution. The sisters almost seemed surprised by that question, Gordon recalled, saying they told her in essence " 'How could we not stay? They can't tell us we're not the church.' "

"For me that revealed — to generalize — the millennial tendency to leave institutions, and the tendency of this older generation to stay within that institution and struggle with it. [Millennials] will leave institutions and hope they change [them by] working from the outside, whereas sisters work from the inside."

Theologian and Franciscan Friar Richard Rohr has spoken about the "edge of the inside," Gordon said, imagery that has helped her see what is happening with Nuns and Nones, or Sisters and Seekers, as some prefer to call it. Sisters, who are not a part of the church's hierarchy, are on the edge of the inside, while millennials who are seeking spirituality are on the edge of the outside.

"We're sort of this partnership that's been created to hold hands across the schism between those inside and outside the institution," she said. "I think that's been a healing and generative process for both of us, to learn from one another on what we're experiencing from where we stand."

Future of religious life

Wayne Muller, one of the founders of Nuns and Nones, said a plaque ought to hang in the booth of the Italian restaurant where the group was sitting: "Here is where the trajectory of the U.S. Catholic church changed on Nov. 28, 2016," he joked.

In that booth, he and 31-year-old Adam Horowitz met with religious leadership about the direction of Nuns and Nones. Sitting with Dacey and Zinn, both former presidents of LCWR, the two founders of Nuns and Nones asked the sisters for their blessing to go further with their vision.

"The scale of what this means to the larger church is so obvious to the people in leadership," said Muller, an ordained Presbyterian minister and author.

Dacey agreed, focusing on the implications these national conversations could have for women religious into the future.

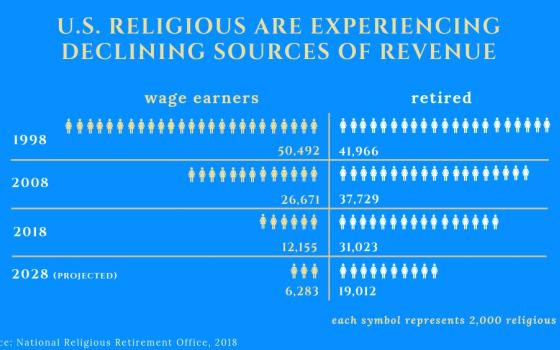

"Clearly the institutional phase of religious life is over, it's dead, it's gone," she said, as 90 percent of today's 50,000 women religious are older than 60. Alternatively, "nones" are becoming a younger and larger share of the U.S. population, claiming about a third of millennials.

Individually and collectively, Dacey said, sisters are wondering: "What is God asking us at this time?"

"There will be fewer structures, and I think we will be very much into ministry of presence," Dacey said, noting that her congregation began with just six sisters walking the streets of France responding to the needs they encountered, a spirit she sees in the millennials today.

In that regard, "we will be much closer to our founders," she said, as opposed to running the large hospitals and schools once typical to U.S. sisters — a shift that has already begun, she added.

Though it's only been around for just over two years, Nuns and Nones (or Sisters and Seekers) has proved to be both a bridge and potential vehicle for the vocation and charisms of religious life.

"Yes, things begin and end, and that's the way of all things," Muller said. "But what if there's another way? We're raising it as a question. Now it's a collaborative wondering."

Co-living and formation project

The diminishment of congregational life in the U.S. is a two-fold concern for sisters: Above all, how can their respective charisms continue after institutional religious life has passed; and (a less moving but more pressing matter), what to do about the oversized properties on their hands?

"It's like a fish in water," Muller said of women religious in large communal spaces. "A lot of sisters don't fully appreciate it because they've always had it." Long-term ideas include investors buying sisters' properties, with sisters continuing to live there but also renting housing or office spaces to millennials.

This past November, a few millennials moved into the Mercy Center in Burlingame, California, sharing grounds with the sisters who run the place, for a six-month pilot program.

But for now, Mercy Center is experimenting with what that could look like on a smaller scale, with other programs around the country to emerge in the next 18 months.

"The sisters around here are saying, 'Oh wow, that's going to bring life into this place,' " said Carle, one of the hostesses.

A couple of years ago, Horowitz decided to adopt an itinerant lifestyle, living out of a suitcase while he ran the U.S. Department of Arts and Culture (a network he created, not a government agency). In early 2018, he stayed at the Mercy Center for a couple weeks, which "made a little more real the possibility" for Nuns and Nones' co-living arrangements.

Following months of conversation — What was the purpose? How do we explain this to ourselves, to leadership? What is the process for participating? — the group eventually put out a call on their website, and soon six millennials signed on to live among Mercy sisters.

"Even if there weren't empty buildings sitting around, there would still be a desire to find a locus, a place where this sharing across generations could happen," Zinn said. Rather than being about real estate, she emphasized, it's about "invitation," adding that the millennials she knows are not just looking for a "tweaked Airbnb."

The current model of religious life, Horowitz said, is brimming with lessons for younger generations, even if "it's not a literal translation from that model to what this generation might create."

One of those translations is the Formation Project. An offshoot of Nuns and Nones, the program began because two millennials met sisters through the initial gatherings. The pilot program began in October and already has 56 participants.

Casper ter Kuile and Angie Thurston, the Formation Project founders, basically created a "novitiate" for millennials, as Dacey described it. Over the last year, she and three other sisters (including Zinn) have helped answer a set of questions around prayer, ritual, readings, charisms, fostering community, and more. The exchange showed "so many parallels to what we did," Dacey said.

"It's all the elements of religious formation that we experienced as sisters. The difference here is that it's online and for people who are married, single, LGBT, from any denomination — could be atheist. But the critical piece here is a desire for deepening spiritual life."

So far, the program includes weekly meetings with mentors, a variety of readings from across traditions, and at the end of the year, a personal vow "for a new way of being," she said.

Future generations and new hope

The movement feels like it's just at the tip of the iceberg for the kinds of communities the moment is beckoning, Horowitz said.

"A metaphor that's been ripe for me is the concept of refugia," he said, describing the biological phenomenon in which "major fires leave behind little pockets of diversity, the seedbeds from which the forest can regenerate." The sacred spaces that they're forming together are like social refugias, Horowitz said, seedbanks of spiritual wisdom and tradition.

While Nuns and Nones has given millennials access to the seedbeds that sisters have been cultivating for centuries, for women religious, "the privilege has been to be invited into those deep conversations by the next-next generation," particularly those outside the vocation of religious life, said Zinn. These are different from conversations with millennial sisters, she added. "Those are sister to sister. This is a different, parallel relationship, and it's a very equal one."

And she sees that "these now-friends of mine are realizing that you need some scaffolding to hold your life together," Zinn said, despite their general distaste for institutions. "Throwing everything out is not acceptable, nor is accommodating yourself to everything that exists acceptable. It reminded me that the journey toward a meaningful life is a sweet spot."

Dominican Sr. Gloria Jones said she senses the millennials "found hope" in the sisters because women religious have "opted out of the dominant social system," while creating "pretty amazing outcomes for the sake of the world."

"The 'nones' wouldn't identify with being followers of Jesus in the same way, but the Spirit works in many ways," she said. "Humans are the ones who put limits, saying it's 'not authentic because it's not lined up with this.' The Spirit is much more creative and expansive.

"I see in these 'nones' hints of similar energies and desire and spirits that gave birth and shape to our religious life."

[Soli Salgado is a staff writer for Global Sisters Report. Follow her on Twitter @soli_salgado. Her email address is ssalgado@ncronline.org.]