The experiment was as eclectic as the items that filled the Mercy Center community room, where for six months Mercy sisters and spiritually curious millennials gathered and lived in this suburb south of San Francisco.

The mix of subjects on the room's bookshelf showcased the range of perspectives of the millennials: Books on new cosmology, anthropology and herbal medicine sat next to books on religious vows and the gift of community life. Jewish prayers hung next to mosaic prints of Catholic saints. Leaning against a wall was a whiteboard with a to-do list, including scheduling talks on composting and spiritual formation.

The grassroots movement known as Nuns and Nones had brought them together, initially through conference calls and in-person gatherings where sisters and millennial "nones" (referring to the box they check next to "religion") could share their passion for social justice, community life and contemplative practices. Within a couple years, Nuns and Nones has already engaged hundreds of sisters and millennials around the United States, with new groups sprouting in different cities every couple of months.

But in the Bay Area, four millennials in their early 30s became the first of the Nuns and Nones group to try out a residency program, temporarily living in a convent to witness and share in a spiritually grounded community life.

"Having so many books in the libraries around here as well as the teachers and sisters coming through created a place where you couldn't escape spiritual wisdom," said 31-year-old David Bronstein, one of the millennial residents.

"That deep spiritual hunger was constantly fed and empowered," he said.

Bronstein was raised Jewish and, like many others involved in Nuns and Nones, doesn't fully identify as a "none." (Some refer to the movement as Sisters and Seekers instead.)

And while the millennials arrived at the Mercy Center in November prepared to ask profound questions on ritual, commitment and communal living, the Mercy sisters who spoke to Global Sisters Report all emphasized how mutual the learning experience was.

"They have invaded my life profoundly in consciousness," Mercy Sr. Judy Carle said. "I'm different because of this little short time of getting to know each one of them individually."

Some continued their jobs but worked remotely; others took sabbaticals or part-time local jobs throughout the residency. All four work in some form of community organizing with art or social justice at the core.

In addition to the millennials living at the Mercy Center, several local millennials regularly joined the larger group discussions or celebrations, while a few others lived in the convent for weeks or a month at a time.

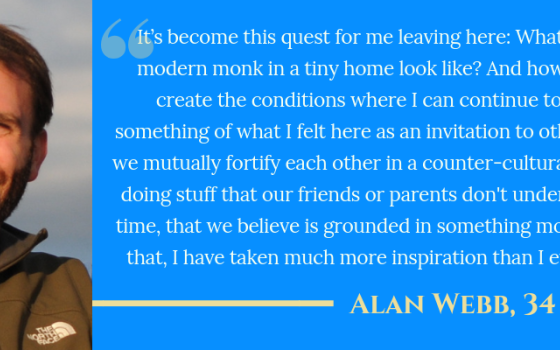

"There's an extended circle of people that we've sometimes joked are like our associates," said 34-year-old Alan Webb, an example of how sister jargon has seeped into the residents' everyday language.

Mercy Sr. Marguerite Buchanan said she often thought how in many cultures, "they don't have the separation of the elders; they are very much alive in the community. And I think this [living arrangement] is getting back to that."

With a "gratitude slam," impromptu poetry and the awarding of mock diplomas, May 13 marked the end of the pilot residency program.

Illuminating conversations

After Adam Horowitz moved into the Mercy Center, the 32-year-old co-founder of Nuns and Nones said he felt more "accountability" for meditation while living with the sisters.

"I felt, for brief moments, what happens when a community is supporting itself in spiritual practice," he said. "It was a little taste that makes me hungry for more."

Meals infused with ceremony, weekly informal gatherings, retreats, workshops and celebrating Shabbat (Jewish Sabbath) regularly brought the sisters and millennials together despite busy schedules.

Hanging out in the community room one day, 31-year-old Sarah Bradley found herself talking to Mercy Sr. Celeste Marie Nuttman, a "delightful encounter that turned into a beautiful and illuminating conversation" that eventually expanded on the vow of chastity.

"Her words really captured my heart when she described her commitment to being this artesian well of divine love and availability for everybody around her," Bradley said. "It made me think there was so much more to the vows, that they were more relevant to me and my generation than we might have imagined."

That chance encounter sparked the vow series, in which poverty, chastity and obedience were independently explored for one evening over the course of a few months. A millennial and a sister partnered for each presentation, with everyone tapping into their networks to invite outside guests who might find the talks inspiring or relevant to their work. Each conversation brought in anywhere from 25 to 40 people and lasted about two hours, embedding meditation, prayer, singing and poetry.

Bronstein described it as "an investigation on how [the vows] can and need to be lived today, finding the home and radical roots of each of them. [It was] also an inquiry for each of us, of what we're committed to or how we're committed to living."

Though Mercy Sr. Joan Marie O'Donnell said she knew her own interpretation of the vows have evolved throughout her 60 years in religious life, "the experience that the millennials brought to this was a more global perspective on the vows — the relationship between the vow of poverty and the condition of our planet and care of the Earth, for example."

Exploring the vows was important to Horowitz, he said, because he sees them as the "foundation of being, the glue that holds a community together."

"With each one, I've come away with language that feels orienting for me," he said. "One sister talked about how the vow of chastity is the vow of learning how to love; poverty, around economic justice; obedience, about heeding the call. It feels like fertile soil from which to make individual and perhaps collective decisions about how to live and then how to show up in the justice work."

When Mercy Sr. Patsy Harney entered religious life in 1961, society was experiencing "protests, Vatican II, assassinations. It was a time of great upheaval, but it was also a time of great hope," she said, recalling her 20s.

"There was this sense that I could make a difference. And when the millennials tap into our critical concerns, I tap back into the '60s. I can ride the wind on their passion about these issues," she said.

Bradley echoed Harney's witness of an overlap between her peers and sisters.

"What they prioritize are the same things that matter the most to me and my community; it's climate and Earth justice, racial and economic justice, women's rights, immigration," Bradley said. "Sure, we might come at it from a different place, but that's a place of grace and mutual transformation."

Commitment and sacrifice are some things Bradley hopes to incorporate into her lifestyle following her time living with the sisters: "What are the commitments that I want to make, and what am I willing to sacrifice or reach for? ... I have so much to learn from their unshakeable commitment."

Bronstein said that before moving into the Mercy Center, he was particularly curious about the intersection of spirituality and activism. He had never met a sister before this experience.

"I felt how important it is to work with existing institutions, working with older people, working with people that are aligned in values but have different perspectives, to see what it can mean to be allies," he said. "I learned from the sisters that prayer is not just a verbal thing; it's an action thing, it's the artistry of how they live life."

'Expanding our zones of awareness'

Beyond exploring questions around spirituality, God and the vows, Webb said a gift of Nuns and Nones has been the sisters' equal openness to discuss the tough questions surrounding gender, sexuality, racism and patriarchy in the church.

After attending a training session in Oakland on "healing from internalized whiteness" in the spring, Webb returned to Mercy Center eager to impart to the sisters and fellow residents what he had learned on the importance of confronting the consequences of a white, heteronormative, patriarchal society.

Carle said the two hours Webb spent sharing what he had learned was "so packed and so giving. ... I felt privileged to be on the receiving end of that, and it made me grateful for the fact of [his] presence."

Webb emphasized the rare gift of being able to have those conversations intergenerationally, how there is a "hunger for elders that are willing to walk with us in that way and ask the hard questions."

The sisters' openhearted and curious attitude prompted Bradley to invite her nonbinary, queer and transgender friends over to the Mercy Center to engage with the sisters. The sisters' welcoming reception of her friends demonstrated an "eagerness to be in solidarity and to be in relationship," she said.

"Having the tougher conversations with sisters makes me super hopeful that we can move through this moment of only seeing what divides ... and knowing that it requires expanding our zones of awareness, brave speech and deep listening," she said.

Mercy Sr. Janet Rozzano said the experience of sharing with the millennials the past six months has been a reminder to her that "as older people, we still have a lot to give. And that in itself is an important ministry."

"The way the Spirit works sometimes, it creates this situation where it looks like we're dying, but out of death comes new life. We see that every spring," she said.

Building relationships with millennial sisters is also something the residents hope to continue to do into the future.

"They're facing the same crises that we are," Bradley said. "So how can we support one another and be a beneficial companion for each other?"

Since participating in the residency, Horowitz said he feels more "permission" to spiritualize his work outside Nuns and Nones. Recently, at a 400-person gathering he organized on arts and social justice, "I had people come up to me and say it was the most spiritual meeting they've ever been to, and saying it with gratitude. [Within] the nonprofit space, so many people are yearning for the level of depth and connection that comes from introducing ritual and the practices of spiritual grounding."

Plans for future residencies

"We've totally made this up on the fly," Horowitz said of the pilot program.

Now, the core team of millennials and sisters from the Mercy Center will consider their recommendations so future residencies can benefit from their wisdom. (One recommendation sisters said they learned early: ensuring the millennials have an oven, not just a microwave.)

Horowitz rattled off a handful of questions they're still pondering: "What kinds of conversations and meetings should they have? What kinds of community agreements? What support structures ought to be in place? What about spiritual direction? What length makes sense? What might a more intentional, action-oriented residency look like?"

How it was funded kept in line with the experimental nature of the residency, with a blend of individual contributions and outside fundraising, Webb said.

He noted that because every millennial resident came in with different work arrangements, the pilot program couldn't resemble the novitiate years that sisters undergo when joining religious life, particularly the deep spiritual formation.

He said the residency program would ideally emulate the canonical year, in which sisters are required during their first year of novitiate (the time before professing their vows) to abstain from work so they can fully dedicate themselves to spiritual formation. Taking a mini spiritual retreat and being thrown back into a hectic work schedule, Webb said, can make it hard to maintain whatever deep spiritual practices retreats inspire.

"I would like future residences to think about how the economics of it work so that people can make preparations the same way that you'd ask of a discerning sister, to put work obligations on hold and either to have the savings or to be supported financially in order to have that dedicated time," he said. He acknowledged that would require conscientious efforts to keep the program from becoming exclusive for privilege.

"This experience has made me dream," Webb said, adding that seeing how sisters' lifestyles support extended periods of retreat and meditation has been "radical inspiration."

The residents also suggested future programs incorporate access to a spiritual director, which they experienced a couple times in the six months and found to be meaningful, Horowitz said.

Harney echoed the value of spiritual directors, calling them an "important ingredient needed for ongoing spiritual practice," with conversations that resemble counseling sessions prompting questions similar to what the millennials have been asking sisters.

Among her fellow sisters, Carle said she's noticed how community life has evolved as the pace of their respective ministry lives slow down.

"Many of us are not in a place where 'doing' is what we're focusing on," she said. "I'm seeing a lot more 'being' among us, and I don't know where that's going to lead. It's not going to lead to more religious life as we know it."

Though Horowitz said he'd be open to participating in an action-oriented residency program in the future — one idea is living with sisters on the U.S.-Mexico border — right now, he's concerned with figuring out what to do with this experience.

"That's our responsibility moving forward now," he said. "To not just run and leave this behind, but to integrate it and continue to be in dialogue with ourselves and each other. Because that's the yearning: Is there a way of life that we can create together?"

[Soli Salgado is a staff writer for Global Sisters Report. Her email address is ssalgado@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter: @soli_salgado.]