In 1956, when a community of Catholic sisters broke ground for Camilla Hall outside Philadelphia, their move to ensure retirement and nursing care for elderly and frail sisters was the subject of lively debate.

After all, vocations to the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Immaculata, Pa., were growing. Immaculata College (now a university) and a girls preparatory school founded by the order, Villa Maria, were flourishing on the group’s 420-acre campus.

“There was discussion [among the sisters] that we’d never need this retirement community,” said Sr. Anne Veronica Burrows, adding that at the time the order of educators, evangelists and catechists numbered roughly 2,400 members.

Now there are around 800 sisters, said Burrows, who served for 12 years as the community’s treasurer, responsible for supervising the order’s “temporal resources,” which include property and finances.

Almost 60 years on, in an environment in which vocations are generally shrinking and many religious orders face the challenge of providing for their frail and elderly members, the move to build Camilla Hall before the construction of the motherhouse across King Road seems prescient.

When Burrows entered religious life as a postulant in 1966, “All I thought I would be doing is teaching people about Jesus,” said the 66-year-old. Now, having acquired a master’s degree in long-term care along the way, she is at the helm of a $19 million dollar renovation of Camilla Hall.

The extensive renovations are being financed through a capital campaign, a construction loan and withdrawal from the order’s retirement account.

When the work is complete, portions of the existing building will have been updated and two additional wings created, accommodating the approximately 200 residents in need of skilled nursing, intermediate or assisted care or who can still operate independently.

Though the strategies for facing these current situations may not be the same in each community, most American orders (both male and female) have to grapple with this reality: A shrinking pool of members being paid for the work they do is being offset by a rising tide of those who need medical care.

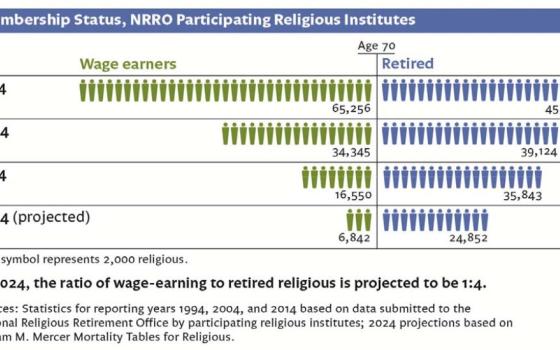

By 2024, the National Religious Retirement Office (NRRO) projects that men and women retired from active ministry will outnumber those being paid for their work by four to one.

Sponsored by the Conference of Major Superiors of Men, the Council of Major Superiors of Women Religious, the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, and the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, the National Religious Retirement Office provides resources and consultants to help religious communities create and implement strategies to care for their elderly members while remaining financially viable.

Yet as religious communities work hard to adjust to the ongoing impact of declining numbers and an aging population, the difficulties they confront are sobering. Only since 1972 have members of religious orders been eligible to participate in Social Security. While dioceses have pension plans for their clergy (though many are struggling with shortfalls), no such diocesan structure exists for female and male religious.

In 1986 a reporter for The Wall Street Journal, John Fialka, estimated that the gap between the assets religious orders needed to support their members and what they actually had was approximately $2 billion, with many living on the verge of poverty. (Soon afterwards Fialka was instrumental in founding SOAR, or Support Our Aging Religious, an organization dedicated to meeting immediate needs for infirm and retired religious.)

“The bad news today is that [the shortfall] is now $4 billion,” said Sr. Janice Bader, executive director of the retirement office. She adds that discrepancies in how some orders calculate financial need and expenses may also lead to inaccuracies in estimating the actual gap, citing this example: “We get reports of one community saying that it costs them $1,000 a year to care for a member, while another may report it costs them $100,000 to provide skilled nursing care.”

To account for the differences in the information received, the retirement office calculates a national average.

Eighty percent of the funds the retirement office distributes, which have averaged more than $26 million a year, go to communities that are severely underfunded, with preference given to religious who are significantly older and frailer, said Bader. (Much of the money the retirement office distributes comes from an annual parish appeal and some from grants.)

Over 26 years, more than $527 million has been distributed for women religious and more than $80 million for men in direct care assistance, according to a the organization’s 2013 report.

The other 20 percent, which has totaled more than $76 million, is allocated to help religious communities work with architects, project managers, financial planners, consultants and other professionals to envision and implement necessary changes.

“The IHM sisters are better-funded than some communities, and they have such a large number of sisters that it makes sense for them to run their own nursing home” said Bader. But given the costs of round-the-clock-nursing care, such a solution won’t work for much smaller groups.

Maryknoll Br. Wayne Fitzpatrick, who oversees nursing and retirement care facilities for his order, said that he’s seen an increase in the number of male religious showing up at an annual conference he helps plan on the topic at Pennsylvania’s Misericordia University. They are asking: “How do we go about this? Where do we network? How do we help each other? Across men’s and women’s communities, how can we share resources?”

“For me this is very personal” Bader said. “I get encouraged by some of the success stories, [but] it’s difficult at times to see some of the communities that are really struggling and don’t have many options.”

She vividly recalls a situation in which one elderly bedridden sister resided on the third floor of a walk up, relying solely on a bedside bell to summon help. In another case, elderly sisters using walkers had to navigate numerous steps to reach their dining room, with sisters in their 80s cooking for the community and only one sister who could still drive ferrying members back and forth to doctor’s appointments – “an accident waiting to happen.”

On the other hand, she said, religious communities tend to be “pretty inventive or creative when it comes to finding solutions to problems. I think a lot of that is going on.”

As a former president of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, Sr. J. Lora Dambroski has also seen religious congregations find innovative solutions to often daunting challenges.

“Religions congregations approach this in many different ways” she said. “Some choose to move together to form a union. Provinces of congregations come together to try to have the best financial and ministry base. [Some] let go of properties that no longer assist in their ministries or are just too much for the members of the congregations.” Some, on the other hand, did put off planning, believing that the large numbers of sisters meant that they didn’t have to be concerned.

“The truth is that we all have to be planning” said Dambroski, saying that the age of large religious orders might be over – at least for now.

To come

The profiles that follow, today through Thursday, look at how four orders approached their retirement needs – taking into account their mission, their financial assets, the condition of the property and numerous other variables – and emerged with solutions appropriate for their local context to face an unpredictable future. They are: the IHM sisters in Immaculata; The Sisters of St. Joseph of Chambery in West Hartford, Connecticut; The Sisters of St. Francis of Assisi in Baltimore, and the Sisters of Divine Providence in Melbourne, Kentucky.

On Friday and Saturday GSR profiles two other communities that are early in the planning process with the retirement office, the Sisters of St. Francis of the Providence of God in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, and the Carmelite Sisters of the Most Sacred Heart of Los Angeles in Alhambra, Calif.

______

Nationally, the retirement needs of the vast majority of religious communities of men and woman who submit information to the NRRO are underfunded. The six communities profiled here are underfunded to varying degrees – from about 6 percent to about 90 percent, Bader said.

Those numbers, based on a national average cost of medical care, are in one sense, Bader said, “worst-case” calculations. That’s because they are based on the full cost of care, minus the assets designated for retirement.

“Some communities may have other assets,” Bader said, “but they are not designated for retirement because they need them for ordinary operations of the rest of the community.”

Bader, who has traveled around the country meeting with religious orders of women and men, sees the decade ahead as a crucial test for many communities. As the large number of women in their 60s and 70s (and older) retire, will the (relatively) younger women be able to support them?

“The next five or 10 years are going to be a critical time,” she said.

“I think the religious life will continue to exist, but some of the communities currently in existence may not,” said Bader when asked to prognosticate.

It is particularly difficult for men and women in religious communities to let go of the work that has for so long defined and enlivened them, said Fitzpatrick, the Maryknoll brother. Yet he finds these later stages of life to be a holy time, encouraging in the elderly what he calls “the spirituality of story-telling.”

Without minimizing the difficulty or pain that communities and individuals feel in making the transitions mandated by age and fewer resources, “in the majority of our communities, the large numbers of our elders are teaching us a lot more than we ever anticipated” said Fitzpatrick.

His concern, he adds, is for those religious communities who haven’t confronted the need to find a new model of life together.

“I’m really worried about communities who haven’t prepared for this stage. It’s upon us.”

[Elizabeth Eisenstadt Evans is a religion columnist for Lancaster Newspapers, Inc., as well as a freelance writer.]