Book review

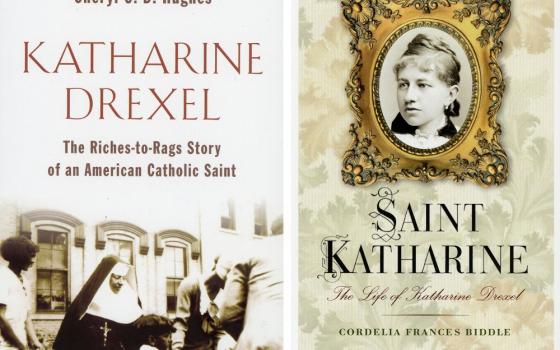

Together, these two very different books about St. Katharine Drexel (1858-1955) provide a full and exacting portrait of the remarkable woman who, indeed, went from riches to rags.

Born a Philadelphia heiress, she divested herself of wealth and privilege to found the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, which has a particular mission of serving African-Americans and Native Americans. The two books complement each other and it is a happy coincidence that both would be published around the same time.

Each author brings particular strengths to her task.

Biddle, who teaches creative writing at Drexel University, is a direct descendent of Francis Martin Drexel, St. Katharine's grandfather. A vivid and direct prose style brings her extensive historical research to life.

Hughes, a professor of humanities and religious studies at Tulsa Community College in Oklahoma, has an excellent command of theological issues. She writes clearly and persuasively about St. Katharine Drexel's religious upbringing, spirituality and the charism of her order.

Riches-to-Rags is a model of contemporary hagiography. While not disguising her admiration and respect for St. Katharine, there is not a hint of sentimentality or romanticism in this presentation of Drexel's piety, mission and canonization.

Hughes gives the reader a full appreciation for the ecclesial context of this remarkable woman's life. We can better appreciate the arduous work and accomplishments of the Blessed Sacrament Sisters because Hughes carefully charts St. Katharine's long discernment process. She quotes extensively from the correspondence Drexel had with her spiritual adviser, Bishop James O'Connor, who for years opposed her desire to enter religious life, and then insisted she found an order of nuns.

In one of the book's finest chapters, Hughes elucidates St. Katharine's kenotic and eucharistic spiritualities "through which she was able to conform herself to Christ, to endure and even to flourish in her vocation as a missionary founder."

Throughout her life, St. Katharine embraced severe ascetic practices, including fasting, mortification of the flesh – wearing a hair shirt, wrapping iron chains around her waist and arms, using a metal-tipped discipline – and praying in uncomfortable positions. "This type of kenosis, or self-emptying through pain, is for the sake of the church, that one may be able to bring others to Christ through the church."

She emptied herself "so she could be filled with Christ in the Eucharist." Her "deep eucharistic spirituality . . . was her defining characteristic." It is a spirituality that she shared with St. John Paul II, who canonized Mother Katharine Drexel in 2000. Hughes concludes her book with a lucid discussion of St. John Paul's pontificate, the theology of canonization and the meaning of the communion of saints.

Biddle's St. Katharine is less concerned with theological issues but her account is wonderfully descriptive and evocative of the saint's life and times. It is one thing to say that heiress went from riches to rags. It is another to read the sumptuous details of her privileged upbringing and watch the development of the "duality in her nature . . . the searching, meditative self who prayed fervently to God for guidance; and the fun-loving teenage girl whom everyone believed was immune to doubt and sorrow."

Biddle conveys the horrific conditions under which African-Americans and Native Americans lived and the enormous physical challenges that St. Katharine and her young community faced as they sought to educate and serve them. She reminds us of the crimes perpetrated against Native Americans and our long history of endemic racism. "Racial inequality was ubiquitous, and most of the Southern bishops either incapable of easing the tension, or turning a blind eye, or, worse, abetting it."

This is not a story of idealistic religious women setting forth to do good in safety. They faced disease, local opposition, arduous traveling conditions, towns controlled by the Ku Klux Klan and deeply rooted injustice.

St. Katharine Drexel spent her last 20 years as an invalid, a difficult challenge for a woman who had led such a vital, meaningful life.

But, as Biddle shows, she used the time as a retreat. "To die to self-love that I may live to God alone is the great business of the spiritual life." It is clear that she succeeded in her business as abundantly as her banking ancestors reached the pinnacle of theirs.

[Linner, a freelance writer and reviewer, has a master's degree in theology from Weston Jesuit School of Theology.]