COP23, the annual United Nations climate change conference, ended in the early hours of Nov. 18 in Bonn, Germany.

The international climate summit, with the Pacific island Fiji serving as president, focused on developing a rulebook for implementing the Paris Agreement, the deal reached among 195 nations at COP21 in 2015 in which every country in the world committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions in an effort to hold average global temperature rise "well below" 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) and to strive to avoid temperature rise above 1.5 Celsius.

The rulebook, which will provide transparency and reporting guidelines for national climate action plans, is expected to be completed before COP24 next year in Poland, where nations for the first time will measure progress so far in reducing global warming. The exercise will act as a basis for pressing countries to increase their nationally determined emissions targets, with 2020 set as the first deadline to do so.

Throughout COP23, which ran Nov. 6-18, a prevalent theme was "ambition" as various reports showed the world behind pace in achieving the goals of the Paris accord, while global emissions are on the rise after a three-year plateau. Currently, nations are on track for a temperature rise of 3 degrees Celsius, and no industrialized nation is expected to meet its target. In June, President Donald Trump announced he would withdraw the United States from the agreement at the earliest possible date (under the deal's parameters, Nov. 4, 2020).

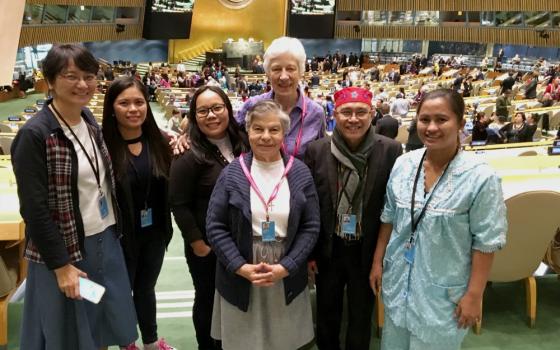

Sacred Heart of Mary Sr. Veronica Brand attended the second week of COP23 through a collaboration with the Maryknoll Sisters. Originally from Zimbabwe, Brand serves as her congregation's nongovernmental organization representative at the U.N. In that role, she has focused on sustainable development and care for the Earth through the Mining Working Group, the "climate-induced displacement" working group of the Committee on Migration, and the grassroots working group of the Committee on Social Development.

Brand spoke with GSR by email during the final days of COP23, which stands for the 23rd Conference of the Parties to the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change.

GSR: What have you observed so far at COP23? What are expectations for what will be accomplished there?

It's important to note that I have been registered for the Bonn Zone [primarily civil society but with some high-level events] and not the Bula Zone, where the negotiations take place.

While the wide range of panels and events have ranged greatly in content and approach taken, there has been a positive energy and engagement with specific focus on climate action and a determination to address the urgency of the climate change crisis, calling states to account to implement their commitments in the Paris Agreement.

The issues faced by small island states have been front and center at COP23. Partly, this is because of the COP presidency being with Fiji, partnering with Germany [which served as host nation since Fiji lacked the resources to hold such a conference], but especially because they are on the front line of climate change and have already faced life-threatening impacts from increased intensity and frequency of extreme weather events.

Various panels have shared stories of resilience and courage of communities already facing devastating consequences of climate change and the steps they are taking to adapt to it and mitigate its effects.

What has Fiji as president brought to the COP?

In their role of presidency of COP, I think Fiji has brought a strong southern and Pacific voice with urgency and beauty. The integration of symbolic and cultural rituals at various moments, the events and information shared in the Fiji exhibition space all helped to bring other values into the COP space, highlighting that climate change threatens the cultural identity as well as the total life and livelihoods of small-island people.

The importance of an integral ecology that recognizes this and the holistic, sacred relationship of people with their environment is often obscured in many developed economies. The voice of indigenous people was certainly heard clearly in the Bonn Zone, and the story motif was effectively used in building a powerful narrative calling for urgent action.

The spirit of global networking and engagement was certainly very strong.

COP23 saw the adoption of the first Gender Action Plan, an effort to increase women's participation in U.N. climate proceedings. What is the significance of that endorsement, and what do women bring to discussions about climate change?

The adoption of the Gender Action Plan is very significant in that it explicitly recognizes the important gender dimension of climate change and names concrete steps to be taken in the next two years to incorporate this. Women are disproportionately affected by climate change but underrepresented in decision-making and planning, although they are often the "first responders" and main protagonists of climate action and resilience at the local level. The experience, expertise and the perspective women bring to issues related to climate change is vitally important to climate negotiations and policy-making.

It is also key to climate action and the wide-reaching transformation of consumption and production patterns that is needed to implement the Paris Agreement and achieve a more sustainable, equitable and peaceful world. Gender equality must be central to a "just transition" to low-carbon economies.

One of the things that struck me most at COP23 was the strong and vibrant voice of women leaders from all geographical regions and backgrounds: grassroots groups, mayors, women taking leadership in caring for the Earth and addressing climate change. From Xai-Xai, Mozambique, to the Amazon region of Ecuador, from Fiji to the First Nations of Canada, to the Maori people of New Zealand and the nomadic pastoralists of northern Kenya, women shared how they are using local knowledge and harnessing community efforts to address challenges coming from changing weather patterns, rising sea levels, droughts and extreme weather events. One key message from women leaders in developing countries was the need for more climate finance to reach initiatives at the local level.

Are people at COP23 still talking about "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home" [Pope Francis' 2015 encyclical on the environment]? How can it have an impact in the negotiations?

At the side events organized around this topic, yes. I only heard occasional references to it in other settings. However, I think the moral case for serious attention to the issue of climate change has been made clearly by a variety of groups and in many different sessions.

The link between the "cry of the Earth and the cry of the poor," respect for human rights, the moral obligation to move beyond local and national concerns to valuing and protecting the common good — all these are some of the ways that it can have an impact.

Climate justice was featured as a thematic day in the second week, and that highlighted issues relating to human rights. The importance of listening to indigenous voices and respecting their rights was highlighted. Other sessions explored such issues as the legal basis for holding corporations accountable for the contribution to climate change that is already "locked in" because of their actions.

What has been the mood of the COP? Has it been affected one way or another by the current U.S. position to leave the Paris Agreement at its earliest opportunity?

One word that comes to mind is "determination."

There was a strong sense that the issue of climate change is too serious and too urgent to be derailed by changing political whims and that people's activism can and must bring about change. I think the current U.S. position to leave the Paris Agreement strengthened the resolve of ordinary people as well as the #WeAreStillIn initiative of U.S. states, governors, mayors and organizations to redouble efforts and to join forces in solidarity and joint action with others globally.

Some of the concerns expressed related to the large gap between governments' words and commitments and what they are actually doing, the inadequacy of the responses in practice, not only in reducing emission levels, but in providing climate financing.

I heard and felt a deep concern that responses are sometimes seen in purely technical terms: for instance, "energy transition" rather than radically reconsidering the changes that need to be made in the global economic system to address growing inequality and current styles of life and unsustainable patterns of consumption. To live more simply so that others may simply live.

Here, I feel that the strong challenge posed by Pope Francis in Laudato Si' has yet to be deeply heard and heeded in the Catholic community.

[Brian Roewe is an NCR staff writer. His email address is broewe@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter: @BrianRoewe.]