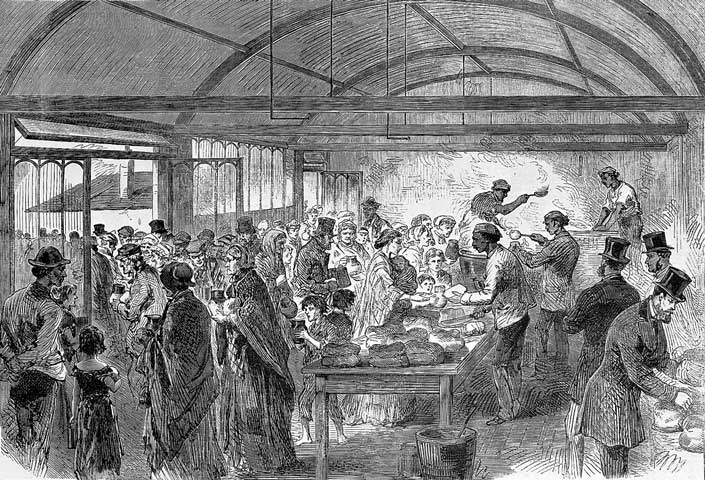

Soup is distributed to the poor in an 1868 image in The Illustrated London News. (Wellcome Library, London)

In what passes for a liturgical calendar in the land of television, we are now in the high holy days of the year. "Downton Abbey" returned to our screens and our homes Jan. 4. The servants' bell marked "Queen Caroline" has rung and we are back in the land where wearing a dinner jacket and black tie to the evening meal is referred to, witheringly, as wearing "your rompers." (Let us all pause for a moment and give thanks that the dowager countess who uttered that line never lived to see the debut of the sweatshirt and sweatpants combo.)

Much of the attraction of this British television series lies with the meals: the breakfast tray Lady Cora receives in bed, the bustle below stairs in Mrs. Patmore's kitchen as jellies and soups and puddings and savories and game birds are stirred, baked, roasted, plated, carried up the stairs and served by uniformed servants wearing white gloves. There are the manly whiskeys decanted from crystal and taken before a roaring fire in the library. And there are the decorous servants' meals, led by Mr. Carson, in which no one rushes, but is yet ready to rise at the sound of a bell and hurry off to serve the Crawleys and their guests.

Then there is the mealtime conversation, careful above stairs lest the servants hear, and careful below stairs lest the name of the Crawleys be taken in vain. We are treated to these exchanges just after most of us have taken part in, and one hopes, survived, the very different sorts of conversation we have at our holiday tables. I grew up with grandmothers as strong-willed as the dowager countess at our table, but not for them the precise, high Anglican parameters ruling Thanksgiving or Christmas table talk. We always reached the point in the meal when the elders discussed someone of our kin or acquaintance who was "jus' et up with cancer" (cue the mournful headshakes), "jus' et up. They cut him open and --" Here some other elder takes up the mournful refrain: "He uz jus' et up."

There were other bits of news to be discussed, many of which ended with my paternal grandmother declaring firmly, "Honey, he jus' needs killin'." There was no bloodlust in the statement; it was more in the way of a public service announcement.

And, always, always, we told jokes. "Do you know why you always take two Baptists with you when you go fishing?"

"If you just take one, he'll drink all your beer."

Downton Abbey is a joke-free zone.

But the food, the food is enough to make up for the stilted conversation. I'm not sure what a savory is but, as I watch the show (in my sweatshirt and sweatpants combo), I want to reach out and snatch one from the serving tray.

Imagine my surprise, then, to come across Ruth Goodman's excellent new history, How to Be a Victorian: A Dawn-to-Dusk Guide to Victorian Life. Goodman writes history from a woman's point of view. Not for her the military exploits of the Boer War. She takes us through a day in the life of Victorian England, from the poor, the working class, the business class and on up to the aristocracy. We read about toilets and transportation and leisure (for those who had it) and sex (Goodman, who believes in trying out what she writes about, has hand sewn a sheep gut condom) and illness, and, always, always, food. (Though Downton Abbey begins in the late Edwardian period and is now in the postwar 1920s, the rules and ways of Victorian England are everywhere still found, even as they are stretched and strained and rebelled against. It is the story of the dying of the Victorian era.)

The meals at Downton Abbey are frequent, choreographed (a servant leaves the house, but not before announcing, "I'll be back before the gong") and abundant. But what Goodman reveals is that, for most Britons, hunger ruled their days. She reports of workers in the south of the country who subsisted primarily on bread, with most of their nutrients and calories coming from the beer with which they washed it down (and their troubles away).

But the most disturbing revelations concern the ways in which food was commonly, and dangerously, adulterated. She writes of watery milk "whitened" with chalk. "Cider and wine," she says, "were sweetened with lead; and brick dust was often used to thicken cocoa."

And those people in the south trying to stay alive on a diet of bread and beer? Goodman writes how large national mills supplanted the small local mills. The local mills ground wheat with all the kernels intact and mixed together. The result was a coarse bread filled with fiber and nutrients. The larger mills wanted white bread, a sign of luxury and status. Goodman writes:

Roller mills had replaced the old stone mills. These were much faster, which made the process significantly cheaper ... However, the nutritional effect was not a positive one. When flour is stone-ground, the wheatgerm is ground along with the starch and mixed around; when it is milled by rollers, it is crushed into a small, separate flake which can be sifted out.

She writes that the roller mills also removed the oils from the wheat, increasing the shelf life of the flour and the bread made from it, but further diminishing its nutrient value.

On second thought, I'll pass on that savory, thanks.

In November, my husband and I took a trip down the Mississippi River from Memphis to New Orleans. We stopped at three plantations along the way. Then we saw the Goodman-like corrective to the Downton Abbey-style beauty at places like Oak Alley in Vacherie, La. One can almost picture the Earl of Grantham coming down the tree-lined approach to the house, his faithful dog trotting alongside him.

In Baton Rouge, we toured the Louisiana State University Rural Life Museum located on 40 acres of the former Burden plantation. It is an agricultural research station and a living history museum dedicated, as our guide told us, to an examination of the way in which "99 percent of the population" of Louisiana lived in the 19th century, both pre-and post-Civil War. Hunger there, too, and malnutrition and worms and grievous injuries from sugar cane cutting: It was the daily life of the Southern poor.

Poverty seems far from Downton Abbey, just as slavery seems far from Oak Valley, both of which fall into the category of Disneyland for grownups, adult fairy tales. And who doesn't like a fairy tale? But sometimes the poor maiden is poisoned with lead, and sometimes the brave little tailor goes blind from the piecework done by candlelight. And sometimes hunger and open sewers besiege the whole village worse than the local fire-breathing dragon.

So I'll be watching, my copy of Goodman's book handy, ready to remind me of my own fairy tales. Like that label in the neck of my comfy sweatshirt I'll be wearing as I loll on the couch, the one marked "Made in Sri Lanka."

[Melissa Musick Nussbaum's online column for NCR is at NCRonline.org/blogs/my-table-spread. More of her work can be found at thecatholiccatalogue.com.]