The questions of our time are also significant, and we are still concerned with sorting, separation. (Unsplash/Forest Simon)

Between the lines of the Easter narrative engrained in my heart is a story I'd rather not tell — a story made up of agonizing questions and the intensities of death and division.

After Jesus ascended, other Gospel characters were suddenly left looking at each other with wide blinking eyes. I imagine the confusion and questions: What now? What next? Each question is an uncertainty to be explored. The book of the Acts of the Apostles reveals the struggle. There are long meetings, homilies, as the community debates big questions: Who can be included? What are the membership requirements? What is a Christian, anyway?

When Jesus was around in the flesh, his disciples asked questions, and after his departure the questions seemed to multiply. Each question like a morsel of bread feeding the communal discernment, each containing a power to shape identity, destiny. I imagine there were several stirring questions that didn't find their way into the biblical text: Are we meant to become something new? Are we resisters of an oppressive empire, or are we part of a spiritual revolution? What types of surrender and sacrifice are essential to show we are dedicated to our faith? So many significant questions.

There was nothing new about the power of questions then; there is nothing new now. In those first few centuries of post-Resurrection grappling, being part of the Christian movement wasn't just a debate, it was dangerous. Lines were drawn. Families fractured. People died. Every apostle became a martyr. When I read St. Paul's letters, I can easily picture the tense bodies and fearful faces within the earliest Christian communities. Many had courage, but others were terrified. Who is a threat? Where am I safe? What will cost my freedom, my life?

The questions of our time are also significant, and we are still concerned with sorting, separation. In the United States, we may have freedom of religion, assembly and expression. But we still struggle with belief and trust.

Advertisement

The COVID-19 pandemic remains serious, deadly. Yet the wide availability of the vaccine in this country means we are turning corners and reemerging after months of isolation. The Centers for Disease Control and the United States government have said once we're vaccinated it's OK for us to be social again, too. Personally, when I learned I was eligible and then booked an appointment for my first shot mid-March, tears wet my cheeks. I prayed in gratitude for answered prayers. Now that I am fully vaccinated, I feel a freedom, a relief, a lightness. I traveled to spend a weekend with my family and joined the celebration for my nephew's first Communion. I attended a small birthday party for a friend.

But along with the arrival of freedom have come feelings of uncertainty. The other day, I was reminded that not everyone is as eager to be vaccinated as I was. I was out for a walk and ran into one of my neighbors getting on his bike to go run an errand. He had a blue medical mask tucked under his chin and his bike helmet on. It had been a while since we had seen each other, so we were catching up, and I casually asked him, "Have you been able to get your vaccine yet?" I rubbed my arm for emphasis, remembering the side effects I felt in my body after each shot, a worthy price for health and safety, I figured.

"Oh, no, I haven't gotten vaccinated and I don't plan on it either," he told me.

I was surprised, confused. And I didn't know what to say. I felt badly that I didn't have my mask on, that I had grown lax in caring for others, because I have started to assume that most people are vaccinated. I didn't want to step back, to avoid the air near my neighbor or be unkind. I didn't want to make any assumptions about him or be rude. I wasn't sure if I'd harm my budding relationship with him if I challenged his views, if I prodded into his reasons for reluctance. I opted to remain friendly and then encouraged him to get the shot. "Oh I'm really glad I got vaccinated. The great thing about it is once you get it, it's unlikely that you'll die from coronavirus." I took a risk in the conversation, and it was uncomfortable.

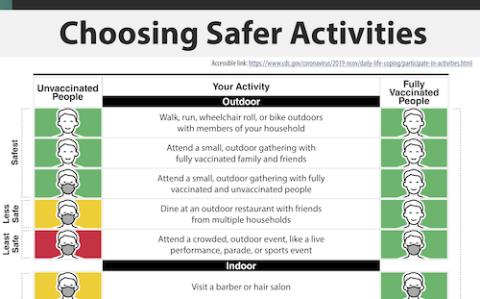

During this time, when some of us have been vaccinated and some have not, when some believe in the value of a vaccine and some do not, we are sorting ourselves into groups. The message coming from the CDC supports the sorting, division, as the vaccinated and unvaccinated must associate differently. Believers are pitted against unbelievers. We are unsure who's safe.

The object of our belief and the content of our questions is drastically different than in the time of the early church. Yet, we are also feeling the intensity of death and division. Now that the vaccinated can associate with those whose belief in the vaccine has prompted them not to get inoculated — we struggle with how to relate to others, with regard to health and safety. Yet Christians are called to build unity, not to separate from others.

Since this pandemic began, we've been learning new ways to be together, to be neighbors and friends. We've learned to live on Zoom and take precautions in person. We had to learn new skills together to connect as a community, and we were made into something new.

As more people are vaccinated and others are not, we are invited to continue learning, to find new ways to be with each other. Aware of the questions and the tensions, we still are called to be neighbor and friend, to reach out — not divide into groups out of fear or frustration. We are invited to open ourselves to others and make choices that move us all into the common good. We are invited to love.

I think I'll start with that neighbor; I will invite him over to visit in the yard.

(Unsplash/Nick Fewings)