Sr. Olivia Umoh, a member of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, speaks with parents and children with disabilities Oct. 13 in a Catholic-run facility courtyard next to St. Peter Cathedral in Kumasi, Ghana. (CNS/Courtesy of SCP)

Editor's note: Global Sisters Report recently held a discussion with Sr. Jolanta Kafka, president of the International Union of Superiors General and general superior of the Claretian Missionary Sisters; Sr. Pat Murray, executive secretary of UISG and member of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary; Sr. Elise García, president of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, and who serves on the General Council of the Adrian Dominican Sisters; and Sr. Carol Zinn, executive director of LCWR and a Sister of St. Joseph of Philadelphia. This is an edited transcript of that discussion.

GSR: With a year of experience with the coronavirus pandemic almost behind us and the promise of vaccines on the horizon, what do you think will be the challenges of coping with COVID-19 in the coming year for sisters and their ministries?

Kafka: This past year, we can say there were two main experiences: loss and courage.

Loss because of the loss of lives, loss of certain areas of mission, and loss because of certain practices of encounter of processes that can be realized only when we are present altogether. We still, I think, carry on this loss. Something that we are not able to live out without is this mutual support in prayer.

Courage because the sisters were always in the first line in contact with those who have been affected in the midst of their communities and in their apostolic areas. Often, sisters were asked to volunteer even if they have not been prepared as nurses, but they offered themselves to serve in the critical areas.

This perspective will be continuing in the coming year of how to stand up from our loss and also how to keep up the courage to bring sisters to and to support mutually the sisters on the front line of the mission.

Murray: The pandemic is not coming to an end in many parts of the world. In fact, the second wave or the third wave is as demanding, and in some cases, it's even more serious. One of the things I'd like to highlight is that sisters are experiencing the very same reactions as people everywhere. They're dealing with fear and anxiety, and there's a real challenge at various levels.

For many of the sisters, even coping with doing ordinary tasks within their communities has been very difficult. For example, when the external people are no longer able to come because the sisters want to protect those who are coming from their homes, then you have maybe a very small group who are managing a very big institution and helping those who are affected in many different ways.

We as UISG have been listening to those struggles and difficulties that the congregational leaders or the provincials are dealing with. We've tried to respond by offering different webinars to leaders and members. I counted the other day: We have offered something like 45 webinars during these months.

Some of these really focus on areas like, how do you deal with anxiety and stress not only for yourself, but also for the people with whom you minister? How do we accompany people who want to pray and reflect and deepen their faith at this time? How do you console people who are dealing with deaths in their own families and also deaths in the community where they were not able to ritualize the normal way? At one level, we are all experiencing this life.

Sr. Patricia Murray of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary is executive secretary of International Union of Superiors General. (Sarah Mac Donald)

I reflected that maybe during the pandemic in the time of the Spanish flu, the sisters were readily visible on the streets and in the homes and in the hospitals and clinics. But also, in certain parts of the world, the sisters are now the people who are the needy. They're suffering, they're in care homes, and they're also fragile with health concerns. Now is the time to give back to women who have dedicated themselves in different countries and overseas as nurses and doctors and catechists who are helping in so many different ways and have given their lives for a long time and now they're frail.

It's an opportunity for others to accompany sisters. Sisters are accompanying those who are ill or those who are worried or concerned, but also others are accompanying sisters at this time. We're looking at the kind of mutuality in which we're facing this pandemic together. That's created a bridge, a real solidarity in a whole new way across the world, among ourselves as religious women particularly reaching out to one another, but also being reached out to by others.

García: We're certainly experiencing here in the United States really having to face the depths of this pandemic in a whole new way once again. For our sisters, being in a situation where we can't just go out onto the front lines and roll up our sleeves and be of assistance in the ways we're accustomed to in the light of emergencies has been one of the real learnings and challenges for us. It has, as Pat was pointing to so beautifully, brought into a realization of the mutuality that we're in it altogether with the people of God, all of us facing this.

We are still too much into this pandemic to really be able to say in any definitive way what is on the horizon. The vaccine, we've just heard, may be available to some of our front-line health care workers within the next two weeks. But we're not going to see it for some time.

There probably will be, even after we participate in vaccination, some hesitation to move back together. This is going to be a gradual unfolding back into what might be normal and, hopefully, it won't be the normal we lived in previously, that there would be some powerful learnings that emerge from this experience that we'll carry into our future.

There are a lot of challenges that our ministries are experiencing that other people are experiencing in terms of businesses and enterprises. We're all facing the same loss of revenues, loss of enrollment when it comes to schools and all those kinds of things that will have significant impact.

Sr. Carol Zinn, a Sister of St. Joseph of Philadelphia, is executive director of LCWR. (Leadership Conference of Women Religious)

Zinn: We are having an experience of our poverty in a way perhaps that we have never had before. Not just the economic aspect of it, but more deeply the notion that we do live a common life and a shared life.

Even if a congregation hasn't had an outbreak of the virus in their motherhouses, they're feeling the same pain and loss when they read in the newspaper that another congregation has had an outbreak and lost so many sisters. There's been a deeper awareness of our oneness, the global sisterhood.

Many of our members are realizing that this experience in the United States is just the tip of the iceberg. So much has been laid bare by this physical reality of COVID: all the structures that are no longer viable; the systems, whether it's health care or education or housing, whatever it might be.

Our members are seeing that those images that have been talked about in terms of COVID being like an earthquake, shaking all the structures of our own personal lives as well as the larger culture and the world. I think the earthquake is being followed by a tsunami. There is a moment, perhaps, where the species as well as all the institutions and religious life, that something's being asked of us.

There's something about the paschal mystery in this. Yes, there's a lot of dying, physically and figuratively. At the same time, we're coming to a soft awareness that there is no return to normal, that in fact, what was before COVID was not normal in terms of relationship structures. We're coming to a deeper awareness of the gratitude for the common life that we share that does provide a security that a lot of other people do not have, even other sisters around the world.

Our members know we are differently secure than other sisters are around the world, so there is a deep sense of gratitude. What we see on the horizon is probably a deeper dive into what is being asked of religious life right now in such a global moment of crisis.

LaShawn Scott, a nurse at University of Louisville Hospital, is inoculated with the Pfizer coronavirus vaccine at the Louisville, Kentucky, health care facility Dec. 14. (CNS/Reuters/Bryan Woolston)

GSR: Has the pandemic and the resulting restrictions caused permanent changes in congregation and religious life or accelerated existing trends? If so, how? What new normals are emerging for congregations and religious life?

Zinn: There is no return to normal. It will be a moving forward. A couple of the things I've noticed that I think will continue that have actually been a blessing of the restrictions is how we gather, and certainly, technology is a given going forward.

But what does it mean to actually gather virtually at a level of deeper relationship and prayer? It's just not jumping on a Zoom call, even though that's part of it. How do we gather? What is really important? What are the conversations we need to be having?

The agenda is being turned upside-down by this experience. What is really important for us to be talking about? What's going to go forward is a clarity reset, really getting some sense of religious life at this moment in the history of the world and church and the U.S.

García: There is no going back to the other normal, certainly in terms of the point that Carol raised about gathering and how we come together. The experience of this last year of forcing ourselves to find other ways, meaningful ways of gathering at the heart level, using technology has been really significant, and it coincides with the imperatives of climate change going forward.

Another area is the whole issue of racism. In the United States, in particular, the way in which the issue of race and racism and white supremacy has caught our attention and arrested us in our cocoons has been really significant and is shapeshifting us as we speak. That is a change that will continue to deepen in us. How we emerge from this with that new sensibility or awakening will be a really important new normal.

Kafka: In this pandemic time, we are realizing the strength of the communion, the strength of listening together, but also this vulnerability of not knowing what is next. This not knowing what is next is somehow humbling us. We need really to give time to listen to each other and search together.

Murray: This has been a time of really deep contemplation and prayer on the reality of our world and our way of life, and also time for conversation. Technology has created a new space, a much wider space for conversation, reflection, journeying and identifying what's important.

I'm very struck by many of the webinars we've held about different topics. They're often in four languages. So for the first time, people are actually visibly seeing one another, hearing the language of the other, hearing the translation and realizing how there's a way in which you can be present to one another even though we're different, even though we speak a different language. As we listen to people expressing their personal experience around a wide variety of topics, our heart and our minds and our tent is being widened.

I actually go back to the talk that I gave at LCWR a year and a bit ago. Some of the things I said I'm now revisiting in the light of today, saying, widen the tent of your heart. COVID invites us to open the tent of our hearts to experience our weakness and vulnerability. It's a new call to being present to one another in a whole new way.

A new kind of arena for being present to one another has been opened up so that there's less focus on action. It's not to say we don't do many good things — we do and will continue to do. But we're looking to the deeper questions about what's the glue that holds us together as religious worldwide, and what is it we're being called to?

One of my big learnings is how flexible religious life is. We pivoted very quickly to the new context in a way that probably we wouldn't have thought of because, particularly in parts of the world, we're older and we're less practically involved. But the real call is around meaning. When you face a pandemic, the questions people are asking are, "What's the meaning of this pandemic for myself personally, for my family?"

Sr. Lijo Joseph of the Congregation of Mother Carmel talks to a patient over the phone in her clinic in Chikmagalur Diocese, Karnataka, India, during the coronavirus pandemic 2020. (Provided photo)

There's a whole wealth of life experience and spirituality that we as women religious have to share, and we are finding creative ways in which to do that. Part of the future or the new normal will be the call to really accompany people and to be accompanied ourselves by others. It's a journey of accompaniment. It's accompanying people when they lose their jobs, accompanying through fear and anxiety.

I was very struck by sisters in India who set up a counseling service that was answering the needs not only of India, but of Africa, as well. Technology can give us a new arena and a new way of creating relationships. It's something you actually have to prepare your mind and heart for. It's not just clicking the link.

Zinn: What we're sliding into is this consciousness at this moment in time about the purpose of religious life, the why of it and the who and the how. How are we sister to each other?

It's not just for ourselves. Sometimes I think that gets misinterpreted, but even our sisters are realizing that whatever they do out there, it comes from this deeper place of this life. That's a grace I don't know that anybody would have ever anticipated, and we certainly could not have hoped for something as catastrophic as a pandemic to just catapult us past our own blinders.

Since we can't get on a plane and go to Rome or visit each other across the country, we've found another way. I'm not really sure that way is going to go away, even when we can jump back on a plane. We're finding in this tragic moment the gift of religious life itself and the ministry that it is in and of itself.

Advertisement

García: The current interculturality and leadership webinars that UISG is offering connect about 200 of us from different parts of the world. It's extraordinary to think about just in the abstract at this time of pandemic that here we are, engaging in this way to really deepen understanding in leadership teams of women religious around the world what it means to be intercultural, to lead interculturally and to live interculturally. It's a wonderful example of what you were just speaking of.

Kafka: This will have an impact on religious life in the coming months because now the process of formation of nourishing our lives is not local. Even that must be inculturated in the local perspective. The possibility of just connecting, and even if you are in the Fiji Islands, you can connect, and your thinking, your praying, your contemplating is becoming wider. This will have impact on future generations and on religious life.

Murray: Jolanta and I have often talked about how we will help those congregations who are smaller and weaker financially not to be excluded from this important moment and this new way of forming and sharing each other.

I learn from my sisters from different cultures and from their experience and from their reflections. One of our aims is to try and extend the connectivity and to encourage people, encourage sisters. The other interesting step has been meeting the needs of leaders, which is the role of UISG, but also meeting the needs of members because that's the desire that leaders have, that their members, too, would be nourished. That has been certainly a shift for us in UISG.

GSR: What about the financial impacts of the pandemic on congregations? Are donors responding? What else is being done?

Murray: Congregations are being affected all over the world. Loss of income, whether it was running small schools or clinics or making altar breads or selling books or religious objects, you name it; it doesn't matter what it is, income is hugely impacted worldwide, in some places more than others. We ourselves at UISG are affected. For example, we have people who rent our premises. They're not able to pay in the same way.

We're all entering into the financial implications of the pandemic. Obviously, in the more fragile parts of the world, it's doubly impacted, like if you have no income coming in because you ran a school or had a small project. Many sisters would say that a lot of projects will not start again, or they have not been able to continue them and doubt they will have the finances to start that particular project again.

We have received about $1.7 million at UISG from donors and congregations. Religious congregations have been enormously generous in solidarity. They have contributed about $600,000 of that amount. This fund comes from both donors and also from congregations. It's a solidarity fund. At UISG, we're distributing that. We have had three rounds; we're on our third round. The first round, we had about $700,000 to distribute.

Then we received finance from the U.S. Agency for International Development in conjunction with Sant'Egidio, a lay organization that does an amount of very practical work on the ground in terms of meeting the needs of those on the margins, but who also do a lot of high-level peace building with organizations.

The U.S. government asked Sant'Egidio and UISG to combine in meeting the needs of those who were vulnerable, both vulnerability within religious congregations initially and also vulnerability among marginal people, unemployed, also people who are homeless, refugees and migrants. Also, we at UISG responded to people who are trafficked and women who are in shelters and to meeting very practical needs. We received about $180,000 in that respect.

The remainder came from donors who saw that we as religious and at UISG could distribute the money very quickly and get it to sisters and congregations in need. An initial fund started with Italy and Spain because they were very badly hit and then moved to Latin America, particularly the six or seven countries in the Amazon basin and helping them.

Then we moved toward the Middle East and communities in the Middle East who were dealing with both conflict and also various levels of destruction and COVID. Then, we moved to Africa, particularly French-speaking Africa and South Africa because another fund had been established for Eastern Africa. Now, we are distributing about $700,000 to Asia and then Africa and Latin America, repeating some of the cycle there.

It's extremely moving to read the accounts of the needs people have and how they're using the money. It's not a huge amount of money per congregation, about $5,000 to $6,000 maximum. But that goes an enormous way when you are buying protective material, cleaning material, when you're supporting families in need, when you're educating people on COVID, when you're helping local communities get water so they can do hand sanitation or you need food because people are now without work.

"Many sisters would say that a lot of projects will not start again."

—Sr. Patricia Murray

I spent most of today responding to applications. We have used our structure at UISG because we're divided into 36 constellations worldwide, and we're able to ask our delegates to reach out to the conferences of religious locally and to make the choices of those who are most in need. That's the kind of process we use, and we can do that very quickly. People respond, and we can distribute the funds.

But it is a whole shift in the work of UISG. This would not have been our work in the past. We don't ever see ourselves as a donor organization. But at a time of pandemic, funds are such a great need and a great support to congregations that we feel blessed that people have been so generous — religious congregations of women and also funders who work with sisters and know their capacity to make the little they get go a long way.

Zinn: The work UISG has done to pivot — I just am really, really grateful. Congregations continue to write and say, "Is there a way we can make funds available to other sisters through UISG?"

LCWR did not set up any kind of entity like that. The request usually comes: "Carol, we have needs, of course. We also know there are sisters in India and all over Africa who have way more needs, so would we'd like to make a contribution." I send them right to UISG. The second thing I would offer is that within LCWR, there's a very informal kind of networking. Congregations are already nicely connected to each other in their regions.

So there's been almost a natural outreach of assistance. It's not at a national level, so I'm not aware of how many and so forth, but I know congregations are helping each other.

The third thing I would say is that universally, the congregations' financial response to the situation was to first and foremost make sure their employees were kept on payroll. I can't tell you the number of leaders that said they're doing everything they can to make adjustments in their budget to make sure they don't have to lay anybody off. To my knowledge, there has been very little of letting people go because the sisters realize that for so many of those who work with us in our motherhouses and senior care facilities and health care facilities, those jobs are important. They're important to us, and they're important to the people that have them.

Sisters of St. Joseph of Peace at the St. Michael Villa in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, write notes to residents of Peace Care St. Ann's and Peace Care St. Joseph's, the two long-term care facilities in Jersey City that cannot have visitors during the COVID-19 crisis. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Peace/Margaret Jane Kling)

Many of the ministries among many of our members at LCWR were thin financially before the pandemic. Certainly, retreat centers are a very demanding ministry financially. A lot of those ministries within congregations were already financially very, very unsustainable. COVID just kind of pushed it over the edge.

The same with some of the educational ministries and even more so with more internally embedded ministries: English as a second language, clinics, the kinds of ministries that are under the umbrella of the corporation of the congregation. They're not separately incorporated. Interestingly, if there are finances that are available, they go to those ministries within congregations to try to sustain them as best they can.

The financial impact to the ministry aspect of several of our institutes has been a dose of reality that decisions that were on their way to being made anyhow about suspending ministries or handing them over to other organizations or to close them, some of that has been accelerated by COVID. While it certainly is heartbreaking, it's not a surprise to a lot of our members. They saw it coming.

Ministries that are able to provide direct services to people at the very grassroots level, those are the ministries that get the financial priority. In the U.S., with the CARES Act and the stimulus packages, there were quite a few of our institutes who were able to access some funds for some of their ministries.

But again, that was done very carefully, because the mindset was: There are so many other small businesses in the United States that really need the funding. So a lot of our members, while they considered it, said, "We are going to apply because we really need it, or we're going to wait because there are other small businesses right here in our own cities that really need the funding."

Murray: A lot of the ministries worldwide in terms of clinics or small educational projects or even community-based projects don't qualify for COVID funding. When a government in the developing world receives COVID money, that would go to the officially linked schools, hospitals, clinics with the government. Often, the entities run by religious orders are private and therefore don't qualify. Therefore, the need was all the more urgent to be able to support that.

Claretian Missionary Sr. Jolanda Kafka is president of the International Union of Superiors General. (CNS/Courtesy of the U.S. Embassy to the Holy See)

Kafka: In the balance of the budgets, suddenly, congregations had to take money maybe designated for traveling and designate it for another purpose that was immediate. For many congregations, technology was the means to keep connected with others. We realized that there are big holes in the map of the world of the possibilities of connecting. We also realized that this horizon of improving connectivity, improving possibilities and skills for using technology will be one of the priorities.

GSR: How has the pandemic changed your organization's priorities, and what are their priorities for 2021?

Kafka: The first voice to ask for help was from the leaders. They want to gather, and they want to discuss what is going on and how to help one another.

There was sometimes a simple, very immediate accompaniment just by phone calls for those superiors general who have lost a lot of sisters. They needed someone just to say they're sorry. It was the experience of person who is in grief. These things were not often published. Even some superiors, they did not want to say how many sisters have died.

Limitation in traveling and in visiting also offered spaces for formation. That's why these webinars were offered, often with different areas of life of the religious. We have been preparing some programs of Pope Francis' agenda. It is very important to also accompany the path of the church. The preparation of Fratelli Tutti took a lot of energy, and later we plan to offer some programs on this.

García: LCWR has really become during this pandemic an essential glue that has connected and bound us together as women religious, as leaders. Early in the pandemic, the national office, similar to UISG, launched a series of initiatives that have been absolutely indispensable to our sense of solidarity in going through and getting through this epic challenge together.

Our national board at our meeting in November acknowledged this in a formal resolution that we presented to the national office staff — Carol, Annmarie [Sanders, a Sister, Servant of the Immaculate Heart of Mary and associate director for communications for LCWR] and the other members of the national staff — in recognizing their outstanding leadership in guiding us through this time. They immediately, as soon as the pandemic started, put out practices for coping, a template for communications, other helpful guidance.

Dominican Sr. Elise García, president of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, serves on the General Council of the Adrian Dominican Sisters. (Provided photo)

They also convened members as UISG did to just enable us to come together to share the fear, the grief, the enormous challenges all of us as leaders were facing, putting it in the context of reflection processes that invited us to be deeply conscious of the transformation occurring in us and in our world as we go through this time. The response was phenomenal, and it was so in tune with who we are as women religious.

They also offered multiple opportunities to engage in virtual sessions of contemplative dialogue. Again, this all just served to deepen our solidarity with one another. And the whole conference agenda continued to move forward in terms of publications, member services, media outreach, and creating virtual formats, reimagining approaches including our assembly, which had to pivot from an in-person to a virtual assembly.

It was just nothing short of extraordinary, what both LCWR and UISG have done to serve leaders and in turn serve our members around the U.S. and around the world.

Zinn: One of the pieces is to continue to find ways where venues are created for sisters, for leaders to be able to be with each other. That is the context, and it's also the content. What we found, as Elise was just saying, is when we offered those opportunities from March to August, our members jumped on those Zoom calls to simply be with one another, to talk about: What is it like for you? How is it going? How do you pray? What are you doing with your senior sisters who are in lockdown for three months now?

Even as we move differently through this crisis now, they hunger for the conversation about how you lead in these kinds of times that are evolutionary. Right now, the pandemic is making it evolutionary. But there's a lot of other aspects of evolutionary times we're living in that aren't going to go away once everybody gets vaccinated.

As conferences of leaders, our responsibility is to keep talking about religious life. Both UISG and LCWR have found that when you gather leaders — those webinars were joined by sisters from all over the world because we were talking about how to live religious life in such a moment of both crisis and transformation — there's a hunger for women religious to be in those conversations.

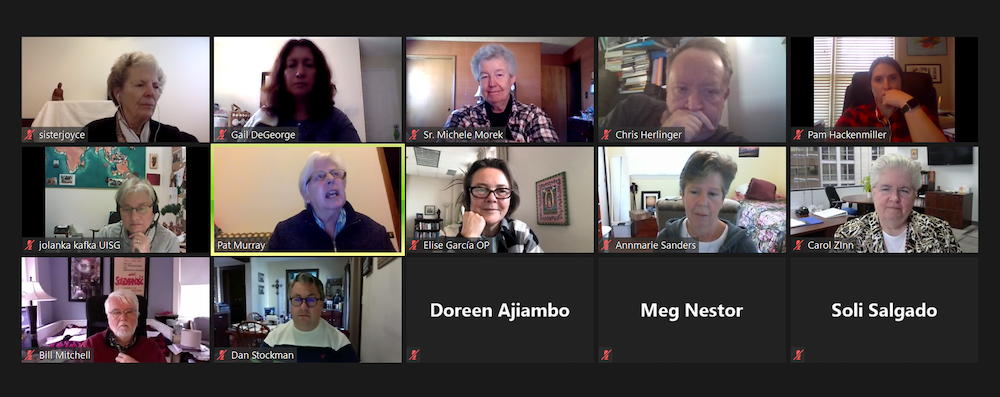

Members of the Global Sisters Report staff meet via Zoom with the leaders of the International Union of Superiors General and the Leadership Conference of Women Religious on Dec. 9. (GSR screenshot)

Murray: That hunger we responded to and those very practical initiatives also came with the request from our brothers in religious life to be part of these conversations. We're very aware at UISG that we want to build initiatives together with the Union of Superiors General. We want to keep our space for women religious, too, but we know there's a moment too to have this joint conversation and joint initiatives.

Already in the area of education, health and interreligious dialogue and the commission for care and protection of minors, we're collaborating together. For men religious, this is a new pathway, too. I think the visibility of men and women doing things together as religious is also a new way forward. It's a different rhythm, but it will be an important rhythm, where we as women religious can give a certain leadership.

Zinn: The weekly reflections we made available to our members, they sent it to their members and they sent it to their associates, to their employees in their ministries. We were getting some responses that there were offices not connected to vowed members necessarily, of lay associates who were using the weekly reflections on a Zoom call with the other people in their workplace or in their ministry site.

Religious life does the work first itself, and then the fruit of that is what gets shared with the larger world. While we did those weekly experiences for our members, they spread it as far as they possibly could because there were opportunities to gather people, to have serious conversation at a deep level of meaning. Where is God in all of this? How do you make meaning out of something like that? I don't think those questions are going to go away after the vaccination.

What is it that religious life is being asked to offer the world now? We're starting to see some image of what that's like: gathering, meaning-making, inclusivity, diversity, mutual respect, and some sense of the whole.

The dietary staff of St. Joseph Villa, the retirement community of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Philadelphia, encourage people to stay home to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Philadelphia)

GSR: Sister Pat and Sister Jolanta, what about the report provided by Pope Francis in May 2019 on women deacons? Is there a plan to release this report? If so, when? What role and input do you hope to have in this new commission that Pope Francis has appointed?

Kafka: When we received the document, we kept it because we didn't know yet the impact of this document for the life of others. The material we have received was just contributing to the historical deepening of the meaning of the diaconate. We were just reflecting among us, and when the new commission came up, we said, "OK, let us wait for the new commission process." We wouldn't interfere in this because in the first stage, we wanted to talk with Pope Francis.

We wanted to have the audience in which we would like to speak about how to proceed, but the pandemic came. [In April, Pope Francis appointed a new commission on women deacons.] We know that the commission is already working, so we now said, "OK, our priority is to continue where we are, and we will wait for the results of this commission."

Murray: In asking the original question, we were also looking at the role of women in the church in general. It wasn't just about ordination in terms of the diaconate and ordination. In a way, the particular question around diaconate and ordination was looking at the traditional way in which decision-making operates within the church. It has generally been those who are ordained.

As Jolanta said, we are allowing the process to take its own. When you look at what Pope Francis says, particularly around discernment and how he reflected on the deliberations of the synod on the Amazon, it's not a question of arguing a case, it's a question about discerning where the Spirit is leading, being prompted by the questions that are arising but taking the time to go deeper. We're respectful of that in the context of this second commission.

I see it as part of Pope Francis' call of this process of deepening the reflection on this particular question and on the role of women in the church. I keep hearing what he says regularly, that he does not want to clericalize women. Clericalism can also exist anywhere in any means. So there are a number, I think, of very significant areas to look at. I think this commission will provide a second group to reflect on what is an important topic.

Kafka: I want to recall another dimension, which we have been discussing in the board of UISG. It was the dimension of synodality. In the context of synodality (and we know that the next synod is dedicated for this topic), we walk together, but each from his or her vocation: This is the first view we have to keep alive in the church, the communality. This dimension of communion is very important for Pope Francis because it is a message for the world, too.

Synodality means not only the institution of synod by the way, but the way of listening to the church, of discerning together with the whole church, and taking decisions as much as possible with the participation of the whole church.

The next synod will be on synodality. It is a very important, key message for the renewal of the church that we know that it is the ground of Pope Francis' desire. He says he has no desire to renew the church. He says, "I am just putting Christ and the Gospel in the center."

"We walk together, but each from his or her vocation: This is the first view we have to keep alive in the church, the communality."

—Sr. Jolanta Kafka

Murray: In a way, in doing that, that's the criteria for discernment. When you have Christ and the Gospel at the center and you're living a context of today's world, you're discerning the way forward for the church. The practice of discernment is something that has to be learned and practiced. It belongs to certain spiritual traditions in the church, but it's now been extended in a much broader and more widespread way.

For example, over the last 18 months or so, the Jesuits in collaboration with USG and UISG have begun a series of workshops in Spanish and in English on discerning leadership: understanding discernment, understanding the best practice in leadership today, and at the same time putting that into the context of the world today. The interesting thing about these particular workshops is they've begun in Rome, and they have involved members of dicasteries and members of religious life, both male and female. I have participated in an English one. I know Jolanta is now participating in one in Spanish.

The idea, then, is to bring this to different parts of the world where the bishop and clergy and male and female religious can participate together in exploring this important topic and in learning the practice of discernment and how to do it together in mutuality and in synodality, bringing our different charisms within the church and bringing those together as gifts and fruits for the life of the church.

It's not just religious orders that have a charism. The magisterium of the church is a charism. too. We sometimes forget. There are different charismatic gifts they're bringing together for the life of the church and the life of the world.

Mercy Srs. Lisa Griffith and Regina Ward, leaders in the Mercy Education System of the Americas, take part in a peaceful protest June 7 in Silver Spring, Maryland. Across the country, women religious have joined in peaceful protests against racial inequality, while others, home for health reasons amid the pandemic, are very much in spirit with the marchers. (CNS/Courtesy of the Mercy Sisters of the Americas)

GSR: During the LCWR 2020 assembly, there were initiatives announced on three separate projects: a five-year commitment to work on dismantling racism, a $1 million fund to support the future of religious life in the U.S. and a national conversation on the emerging future of religious life. What's the status of those initiatives?

García: All are moving a pace. I'll speak to in particular what we're calling a spirit call within a call to address racism and white privilege. It's a five-year journey that we've committed ourselves to. This is going to be a long-term unfolding, not something we would be reporting on anytime soon.

What we have initiated is a process of what we're calling a leadership community within LCWR, which consists of the national board, our region chairs, and members of the national office staff working to committing together to a process with a facilitator primarily focused on the issue of white privilege, white supremacy, since the makeup of the leadership community is largely, predominately white.

That's a commitment that we're making. It involves about three hours' commitment each month over the course of the next 10 months. It really involves looking at both personal and systemic racism in a very rigorous way. We recognize that this whole issue of racism is multilayered and it's not something that you can address with one action. There are multiple pathways we're taking.

Another pathway is an engagement with the National Black Sisters' Conference. We have engaged in two conversations board to board with one another and have a commitment to continue those conversations going forward. That's really about deepening relationships with one another toward transformative change.

We also are looking at some point at wanting to unpack the role of the church in racism and the history of the church going back to the Doctrine of Discovery and their impact to the present day, the role that Dr. Shannen Dee Williams a couple of years ago unpacked for us, the roles of our individual congregations in colluding, I would say, with racism.

Then also looking as Catholics at the wonderful, vibrant history of Black Catholics in our history and raising that up. Most of us are pretty ignorant of the role Black Catholics have played in our Catholic Church. We could also add to that the role of Latinos and Asians. So really expanding our horizon of what it really means to be a Catholic.

Then, of course, another layer in our journey involves the justice work we've been engaged in that our members reaffirmed in this last year or two of looking at it through the lens of intersectionality of climate, racism and migration.

This is not a checkmark of "been there, done that," but rather, it's a journey and something that will be unfolding. It has, despite the pandemic and perhaps because of it, brought us to a depth already of commitment and engagement that we are committed to carrying forward.

Dr. Shannen Dee Williams, left, answers questions posed by Dominican Sr. Gene Poore from the audience during an interactive webcast presentation August 5, 2017, with the Dominican Sisters of Peace. (Courtesy of Shannen Dee Williams)

Zinn: The other two movements have not been hampered at all by COVID. The national discernment actually has been going on since 2014. LCWR was providing transition services to our members where our leaders would be able to engage in this service. We had one leadership team at a time to do some discernment about what they see unfolding for their historical institute, for their religious institute. So that's been ongoing.

The shift we announced last August is that we are having that conversation nationally now, not just one institute at a time, but a national conversation. Our members understand that they have to know what's going on in all the membership of LCWR as we move forward, not just their own institute.

In terms of the designated fund that we established, that is going to begin to roll out in early 2021. We see certainly the work again on dismantling white privilege, white dominance and racism. We see that intricately connected to this ongoing discernment about the future emergent of religious life because one of the ways we've been talking about the future emergence is, how do we organize ourselves as women religious for mission?

In this country, the mission that is just staring at us is this incredible inequity around race that has been going on for a very long time.

Religious life is first and foremost a ministry to the world, and it is already continuing. It's very alive and well. There are over 200 entrants each year in the United States annually for the past couple of years. It looks like that's going to continue. It's just got a very different picture of what it's looking like here in the United States.

We're paying attention to that outer movement around racism and white dominance right now in the culture and in the church. How do we attend to what our responsibilities are as leaders in each of our congregations right now and keep our eye on the very viable emergence of religious life in this country?

GSR: There has been an increase in secularism in many African countries and a decrease in the number of people joining religious life. Is secularity one of the reasons? How should different congregations attract more young people to enter into religious life? There's also this concern about the aging sisters in Africa. What is the plan for these elderly sisters?

Murray: Conversations have begun in different parts of the world, particularly in Africa, about the care of elderly sisters. It's not a simple matter because in many countries, there are no pension funds, though in many countries, the provision of some sort of facility would be costly, so it needs to be well-planned. Also, medical care for sisters in different parts of the world is a big challenge.

Conversations have begun with conferences of religious, both international and at local levels, to begin to see what might be a way forward. Also, there are donors who are concerned for sisters in their elderly years in parts of the world where there is little protection. It's the beginnings of a conversation.

In terms of secularism, there are many reasons why numbers decrease in a country. As opportunities for women to respond and live their baptismal vocation in service open up, women are discerning possibilities. There are sociological reasons as well as broader questions around secularism and globalization and many other factors. It's a very complex situation.

Kafka: The situation is very complex. There is also a certain movement in the understanding of religious life more in the prophetical way as a presence of consecrated women. Many institutions of governments are fulfilling the services that were led by sisters.

The crisis is coming also from within the church, where I find two gaps. One is incarnated spirituality. I mean the spirituality that is connected to the Gospel but at the same time connected to the life, to the commitment in the everyday living. The development of the spirituality will allow young people to face the question before God, "Lord, what do you want from me?" Because it will be not by attraction but by discernment, I hope.

Now, we are going to the second difficult point that I find in our days: the difficulty to enter in dialogue with the youth generally in the church, in society itself. The youth are becoming a group of particular language, particular behavior, particular desires that are different from all patterns we have. Even if we are 10 years older than they, we have difficulty to dialogue, to encounter. We have to find ways to reflect approachability, simplicity, maybe also knowledge of our limitations, but we should not leave the youth without our accompaniment. This is another challenge for religious life in many ways, and not only in a particular place.

In the past, maybe we were more holding on to the charism almost as property of congregations or the church itself. But we are learning from people, from the laity, how they are welcoming the spirituality and the charismatic meaning of the word in the association or without association, but drinking from the wells of the charism. As we work to destroy the walls between races, between nations, we have to also make our walls of congregations more permeable to the encounter of others.