In this file photo dated Sept. 7, 1988, director Martin Scorsese, center, poses with the stars of his film, "The Last Temptation of Christ", actors Barbara Hershey, right, who plays Mary Magdalene, and William Dafoe who plays Christ, at the Venice Film Festival. The film released in 1988 in the face of denunciations from religious leaders. (AP photo, File)

When Sinéad O'Connor tore up a picture of Pope John Paul II during a performance on "Saturday Night Live" in October 1992, many in the secular world denounced her for it. But conservative Catholics went one step further, framing the incident as an attack on an oppressed church — a framing that persisted even after O'Connor said in an interview that it was intended as an act of protest over priests sexually abusing children.

Ten years later, thanks to an investigation by The Boston Globe, the world learned that O'Connor had been right. The incident remained a cultural touchstone, exemplifying both the inclination of a powerful church to position itself as a victim and the ambiguous role of religion in the secular arts world of the late 20th century.

O'Connor's action came close on the heels of a decade fraught with public battles over religion and the arts. Martin Scorsese's film "The Last Temptation of Christ" was released in 1988, in the face of denunciations from religious leaders like Jerry Falwell and Cardinal Bernard Law. The previous year, artist Andres Serrano debuted "Piss Christ," a photograph of a crucifix submerged in urine, and in 1988 Indian author Salman Rushdie published his novel The Satanic Verses, inspired by the life of the Prophet Muhammad.

A year later, Republican Sen. Jesse Helms spearheaded a campaign against Serrano's work, and Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini of Iran issued a fatwa against Rushdie. Meanwhile, conservative Catholics raised an outcry about Madonna's "Like a Prayer" music video, which featured extensive Catholic imagery. Art and religion were in conflict, and the terrain of the sacred was their battleground.

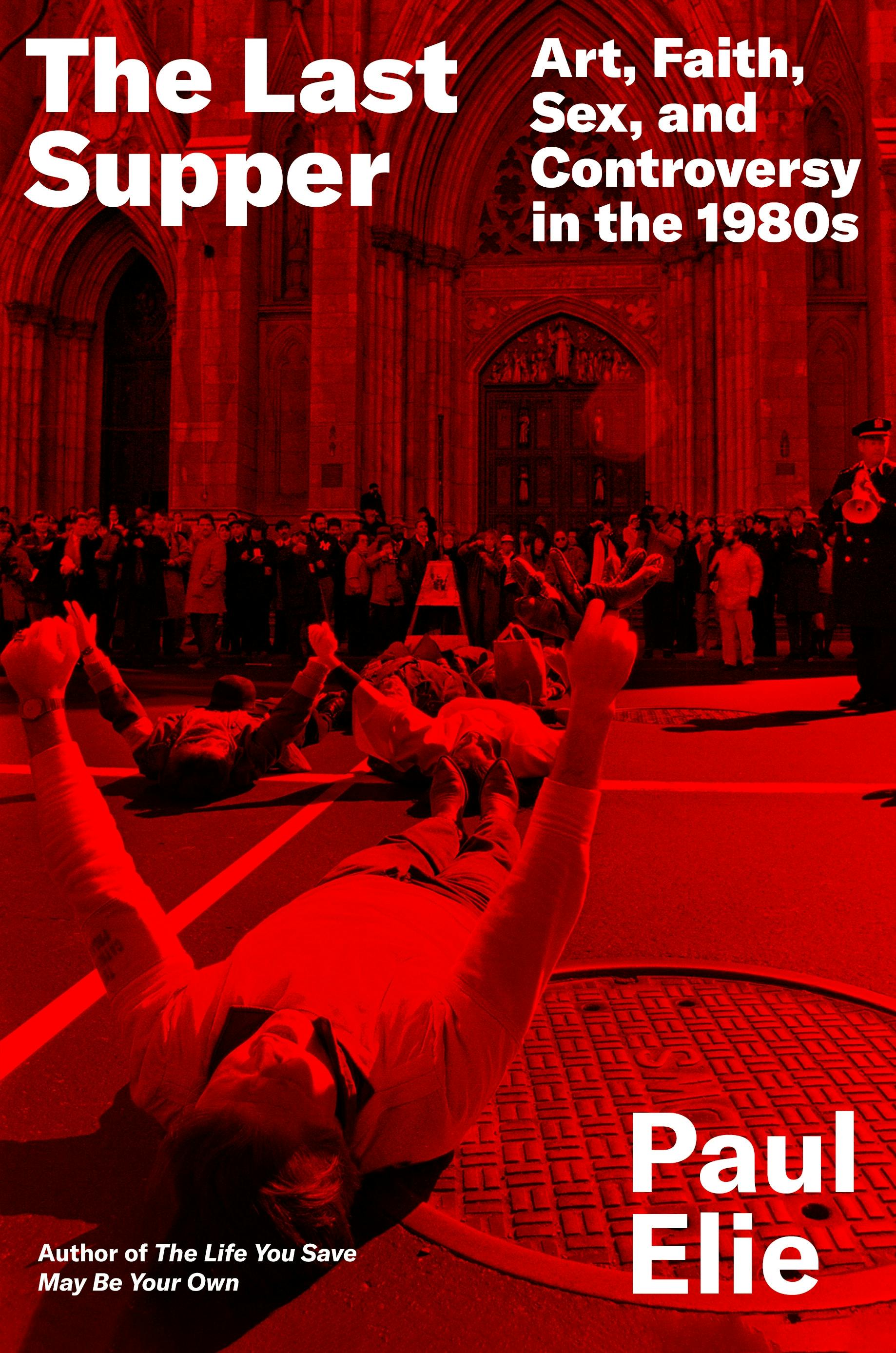

This is the era Paul Elie explores in his new book, The Last Supper: Art, Faith, Sex, and Controversy in the 1980s. As a Gen X Christian for whom both authoritarian religion and subversive art were formative, I found The Last Supper evocative. But Elie's exploration of the struggle between art and faith in the 1980s offers valuable insights for anyone seeking clarity on faith in public life today.

The Last Supper explores the preponderance of "crypto-religious art" in the 1980s — that is, art that uses religious ideas and imagery to articulate "something other than conventional belief." Political analysts have written much about the shifts of allegiances during this era, but Elie, in this "sequence of tales of the crypto-religious," offers a fascinating and meticulously researched look at cultural currents in that shift, relevant for comprehending our troubled "cultural present."

The title of Elie's book is itself crypto-religious, characterizing the early 1980s as "both an end and a beginning." Just as the Last Supper marked the end of Jesus' ministry and the beginning of the church, the 1980s were a transitional time. An era of social upheaval was ending, and the "unsettled relationships among beliefs, institutions, and society that define the present moment were beginning to make themselves felt."

Madonna's "Like a Prayer" music video, which was released in 1989 and featured Catholic imagery, is one of the controversies explored in Paul Elich's new book, The Last Supper: Art, Faith, Sex, and Controversy in the 1980s. (NCR screenshot/YouTube)

The artists who show up in the book each relate to Christianity in different ways, but all use its images and themes to explore inner conflicts or address social issues. Elie weaves together narrative strands involving James Baldwin, Andres Serrano, Bono, Sinead O'Connor, Madonna, Martin Scorsese and others for whom religious expression was essential to their aesthetic output. He discusses Andy Warhol's pursuit of sacred presence, Jack Kerouac's quest for the beatific vision, Patti Smith's "apocalyptic romanticism" and Leonard Cohen's "agony and ecstasy."

For many of these artists, religion was deeply personal, a path through the inner valley of the shadow. That inward turn was idiomatic for an era renowned for its individualism, yet crypto-religious artists drew on Christianity to address social and political challenges, too, including war and the AIDS crisis. For Black artists like James Baldwin and Toni Morrison, Christian symbolism was a powerful conduit for addressing racial injustice. Baldwin, Elie writes, became "a kind of Jeremiah," uttering dire and necessary warnings. And in her novel Beloved, Morrison uses religious language to give voice to a dead Black child, to "speak the unspeakable."

It's worth noting that crypto-religious art is not an exclusively modern phenomenon, nor does crypto-religious art necessarily correlate with heterodoxy or unbelief. But as modernity carved out more space for secularism, non-Christian and ex-Christian artists drew on the iconography of the church to work out their complicated relationships with belief. Decades before Andres Serrano submerged a crucifix in urine, James Joyce used Catholic imagery to articulate a humanistic aesthetic, asserting art's power to transmute the ordinary. His Ulysses, published in book form in 1922, remains one of the most banned books of all time.

Advertisement

As society grew more secular and religion more pluralistic, the relation between them became ambiguous. Artistic expression moved from imagining no religion to imagining religion outside the box. Institutional Christianity has rarely looked favorably on crypto-religious art, and in the 1980s skirmishes between art and church became a turf war. Conservative culture warriors who bemoaned the disappearance of religion from public life were horrified to see it brought back on terms other than their own. To their mind, putting religion into controversial art was blasphemy. "The body of Christ must be kept clean," Elie writes. To put Jesus into the mess of human existence, into temptation and ambiguity and literal bodily fluids, was scandalous.

Conservative culture warriors who bemoaned the disappearance of religion from public life were horrified to see it brought back on terms other than their own.

Yet, ironically, that scandal – God entering the vile body – is at the heart of Christianity. Also ironically, as Elie points out, the church itself abolished the distinction between sacred space and public space by meddling in public life. The campaigns against crypto-Christian art were about power.

Catholicism especially was, as Elie puts it, "a locus of strife." This was due in part to Catholicism's rich aesthetics and imagery, so inviting to artistic use. But it was also due to the Catholic Church's sense of social mission. The culture wars are a dispute about the nature of that mission. Catholic activists like Daniel Berrigan cared for AIDS patients. While Cardinal John O'Connor of New York is said to have visited AIDS patients, he actively opposed prevention like the distribution of condoms.

While most of The Last Supper focuses on conflicts between art and Christianity, Elie connects them with the fatwa against Salman Rushdie, and notes that O'Connor sided with Rushdie's critics, even if he didn't approve of the fatwa. Between the 1980s and now, the Christian Right in the United States has rejected democracy in favor of totalitarian theocracy, like the ayatollah's, but with a Christian twist. As Elie puts it, the connection between religion and violence has been made "straight and narrow as a gun barrel."

Yet for crypto-Christian artists, Elie writes, religion isn't a "structure of historic oppression or a bad influence to be opposed on principle," but rather "inheritance and legacy, underworld and promised land." I submit that it is both, and the conflict in our culture is over which version will triumph. Elie's book is a reminder that creativity is a part of resistance.